Preface

This book is about the principles behind the open government data movement and its development in the United States. The movement is framed as the application of Big Data to civics, where Big Data is not just the size of data but the ability for data to change the way we understand its subject. Topics include principles of open government data, the history of the movement, applications to transparency and civic engagement, a brief legal history, data quality, civic hacking, and paradoxes in transparency.

This book is organized into chapters covering the movement and its history, examples and a typology of open government data applications, a brief legal history of open government data, principles and recommendations for creating open government data, and limitations in the use of data for government transparency. The appendix includes excerpts of open data policy language and model language.

I should note several limitations of this book. First, it is from a distinctly United States perspective both in terms of the history of the movement and in the expectations for government data given by the principles in Chapter 5. Second, open government data is only a small part of the broader open government movement which encompasses classic open government (such as the Freedom of Information Act) as well as the newer fields of citizen participation and collaborative innovation. Finally, a disproportionate number of examples in this book are taken from projects related to transparency for the U.S. Congress. These limitations can all be explained by “write what you know.”

I would like to acknowledge Justin Grimes, John Wonderlich, Jim Harper, Carl Malamud, David Robinson, Harlan Yu, and Gunnar Hellekson for their contributions to my thinking about our field. In addition, I thank the Transparency Camp organizers, where much thought on this crystallized. And I thank my mom for her help editing.

* * *

This book can be read online at http://opengovdata.io. Some links are only in the online version. This is edition 1.1b — June 2012. Updates will be posted to the website.

Other useful resources about open government data and the civic hacking movement can be found at wiki.civiccommons.org and opendatahandbook.org.

* * *

Joshua Tauberer (@JoshData) is the creator of GovTrack.us, which launched in 2004 and spurred the national open government data community. He was also a co-founder of POPVOX.com, a platform for advocacy. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in linguistics and is also published in Open Government: Collaboration, Transparency, and Participation in Practice (2010, O’Reilly Media).

Contents

1. Big Data Meets Open Government

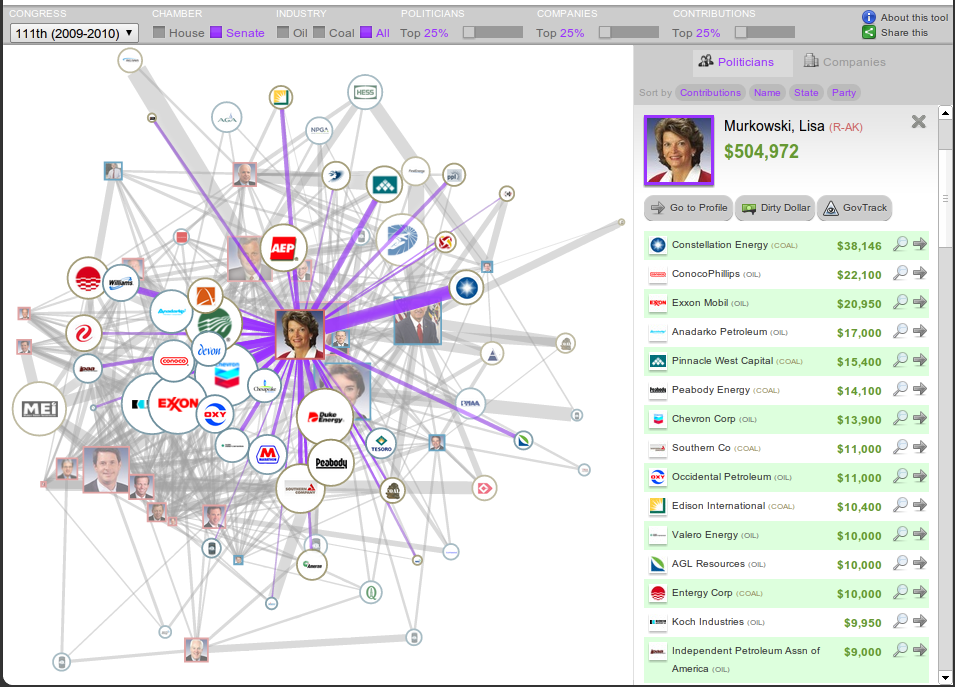

On March 20, 2008, lawyer, professor, and undisputed hero of technology geeks Lawrence Lessig made a career change. Well known for defending the freedom of speech before the Supreme Court against the expansion of copyright law, and for his books on the subject, on that day Lessig announced a new project. It was an organization named Change Congress with the goal to reduce the systematic, institutional, and of course unwanted influence money has on policymaking.

Influence, he might have said, starts with the campaign contribution check. Then it’s tickets to fund-raising events where one might rub shoulders with a future policymaker. There are corporate lobbyists who bring back large returns to their employers by “helping” lawmakers craft the law. And, lawmakers themselves may be keeping in mind a possible future career working for the very corporate interests they are regulating today.

This sort of corruption is “not the most important problem, it’s just the first problem . . . that we have to solve if we are going to solve other problems,” Lessig said at the launch of Change Congress at the National Press Club.1 Corruption gets in the way of good public policy, and if not that then at least public trust, he said. But it’s hard to market an idea that one admits is low down on the list of pressing issues before the country.

But what if the institutional character of government is the issue Americans actually find most important? Somewhere in history the idea that Americans care just as much about process as policy got rejected, and process fell out of favor as a legitimate policy question. Concern over whether states should elect representatives proportionally or by district plurality, how many seats Congress should have, whether Congress should have more or fewer committees — these issues are now considered marginal, inconsequential, and elite. It wasn’t always this way. Five amendments to the U.S. Constitution all having to do with government process were ratified between 1951 and 1971.2 The last major reorganization of Congressional procedure was enacted in 1970 (it addressed the power of committee chairs, among other issues), though it was covered in only 23 lines in The New York Times.3 Our Revolutionary War was started because of concern over process (summed up well in “no taxation without representation”) and resulted in a nation only after considerable debate over the form of the would-be government. Where policy was considered, the Constitution included only provisions that specified what government could not do, rather than what it should do. Contrast the U.S. Constitution with the 2010 Constitution of Kenya, which made policy as important as process in addressing such issues as slavery, health care, labor relations, and the environment. If process was the issue of the day in 1789, and still something debated as late as the 1960’s, it certainly is not today — and that should be a concern if you believe citizens actually do care deeply about process.

Yet a February 2012 Rasmussen poll of likely voters found “government ethics and corruption” to be edging out taxes, social security, and education, and well above two of the previous decade’s most popular issues, immigration and national security.4 Considering quid-pro-quo doesn’t have a tangible presence in the daily lives of people who are not professional politicians, we shouldn’t underestimate how important it is to us not to have our trust violated.

In Stealth Democracy (2002), John R. Hibbings and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse make the case that fairness is far more important to Americans than anyone has realized, and that it is trust in government rather than policy issues that underlies significant aspects of Americans’ civic behavior. In a survey they conducted, approval of government was strongly influenced both by whether the individual believed their government was enacting the right policy and also and almost as much by whether their government was conducting its business in the right way. It’s not surprising that process affects approval of government, but it is surprising that the relationship was strong, and stronger than, for instance, an individual’s personal economic situation.5 Perhaps even more importantly is the effect on civil unrest. Individuals who responded that they would disobey the law if they thought it was wrong were not those that actually thought the law was wrong, but rather were those who thought government process was wrong.6 In other words, Americans can believe in the rule of law even if they disagree with the law, but only to the extent they think the law was made in good faith.

That’s not to say that process has been standing still, and if there is a focus on any aspect of government process today it is on the public’s right to government information. By the time the World Wide Web was coming around the United States already had relatively strong freedom-of-information laws. The Freedom of Information Act had been passed several decades earlier. But digital technology is changing what freedom of information means because technology creates new applications for government information.

Digital access to government records began at the infancy of the Web. The Government Printing Office (GPO), which is the publisher of many of the government’s legal publications, went online in 1994 with the Congressional Record (one of Congress’s official journals), the text of bills before Congress, and the United States Code.7 The Republican Party, which was in the minority at the time, published its Contract with America that year with an emphasis on public accountability. Though the Contract did not mention the Internet, it was the new Republican House leadership the following year that created the website THOMAS.gov in January 1995, the first website to provide comprehensive information to the public about pending legislation before Congress. Later that year the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted a system originally created in the private sector to disseminate corporate filings to the public for free (more on that later). In early 1996 the Federal Election Commission (FEC) opened www.fec.gov, which was not only a website but also a repository of the raw data the FEC compiled. That data could then be analyzed independently by researchers and journalists.8 That year the Census Bureau made the Internet its “primary means of data dissemination.”9

Partisan politics may have driven some of this innovation, as in the case of THOMAS.gov, but information access was not confined to the Republican party. The 1994 “Circular A-130,” a memorandum from the Clinton Administration to executive branch agencies, might have been the earliest official policy statement asserting the public’s right to know through information technology that was itself made available on the Internet. It read, “Because the public disclosure of government information is essential to the operation of a democracy, the management of Federal information resources should protect the public’s right of access to government information.”10 Still, high level policies like those expressed in Circular A-130 don’t typically trickle down through federal agencies without some external pressure on the agency.

The opening up of the SEC’s EDGAR database, mentioned above, was one of those cases where external pressure was crucial. Since 1993, EDGAR has been a database of disclosure documents that various sorts of corporations are required to submit to the SEC on a regular basis. The disclosure documents have been intended to ensure investors and traders have the information they need to make informed decisions — making for a fluid trading market. However, in 1993 the “Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval System” was not available directly to traders. It was run under contract by a private sector company which in turn charged “$15 for each S.E.C. document, plus a connection charge of $39 an hour and a printing charge of about $1 a page.”11 But to Carl Malamud and others including Rep. Edward Markey, the price kept the information from many more traders who could not afford to access the information supposedly needed to make informed trades. (For comparison, at that time access to the Internet for an individual cost around $2 per hour.)

In a carefully executed series of moves Malamud was able to successfully incentivize the SEC to publish EDGAR to the public directly. With help from a grant from the National Science Foundation, contributions from other technologists, and New York University, Malamud bought access to the full EDGAR database and began making it available to the public, over the Internet with search capabilities, for free.12 Then after nearly two years of running the service and distributing 3.1 million documents to the public, Malamud fulfilled his stated plan to shut it down — but not without some fanfare. A New York Times article contrasted the SEC’s legal obligations with a stubbornly dry press statement:

The [Paperwork Reduction Act] says agencies with public records stored electronically have to provide “timely and equitable access” in an “efficient, effective and economical manner.”

“The law is real clear they’ve got to do it,” Mr. Malamud said.

But a spokesman for the commission, John Heine, said it was “too early to tell” whether it would take over Internet distribution of the Edgar documents. Mr. Malamud is asking “some of the same questions we’ve been asking ourselves,” Mr. Heine said.

. . .

“We’ve done two years of public service, thank you,” Mr. Malamud said, adding that he had personally financed a portion of the project.13

Four days later the SEC changed its position14 and worked with Malamud to adopt his service as their official method of public distribution over the Internet. Malamud’s technique was effective, and he has repeated the technique since: buy and publish government data, change public expectations, and then shame government into policy change.

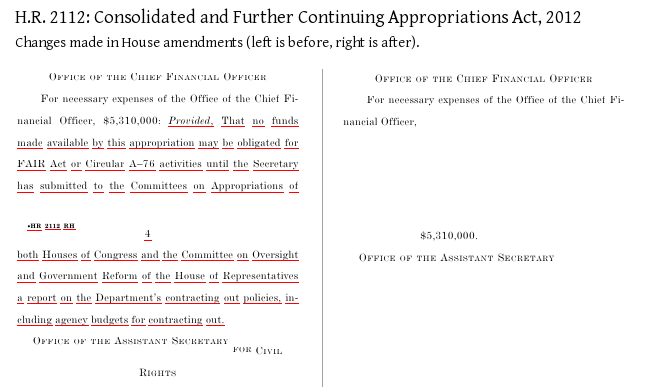

The events of 1994–1996 laid the groundwork for major changes in the government transparency movement that would ocur some time later. But in the first ten years of the government going online, information technology was seen only as a tool for fast and inexpensive information dissemination. Data liberation, as it is called, is only the first part of open government data. What GPO began putting online in 1994 were the same documents it had been printing since 1861. That was absolutely the right place to start, and those documents are still crucial. Legal and scholarly citations today are largely by page and line number, so it is important to have electronic forms of printed documents that are true to the original’s linear, paginated form. But open government data can be so much more.

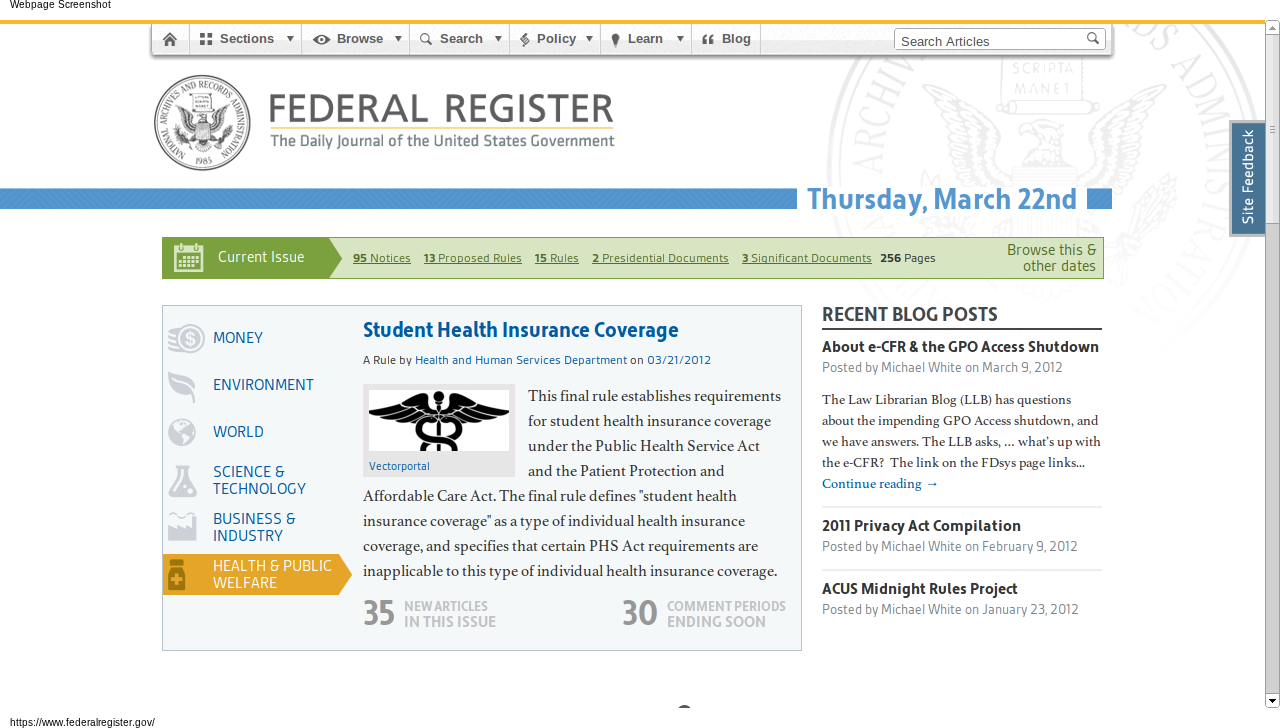

It wasn’t until 2009 that GPO recognized legal documents could be useful in other electronic forms as well. Information technology can make it easier to search, sort, share, discuss, and understand government publications — not just read them. Along side its publication in plain-text and PDF of the Federal Register (the executive branch’s publication of notices and new rules) GPO added a database of the Federal Register in XML format, a data format that makes it possible for innovators in the private sector to create new tools around the same information.15 The Archivist of the United States explained what happened next on his blog:

In August 2009, Andrew Carpenter, Bob Burbach, and Dave Augustine banded together outside of their work at WestEd Interactive in San Francisco to enter the [Sunlight Labs Apps for America 2] contest using data available on data.gov. Understanding the wealth of important information published every day in the Federal Register, they used the raw data to develop GovPulse.us, which won second place in the contest. In March 2010, the Office of the Federal Register approached the trio to repurpose, refine, and expand on the GovPulse.us application to bring the Federal Register to a wider audience. Federal Register 2.0 is the product of this innovative partnership and was developed using the principles of open government.16

The new Federal Register 2.0 (federalregister.gov, shown in Figure 1) makes the Federal Register publication vastly more accessible to anyone who is not an experienced government relations professional through new features including search, categorized browsing by topic and federal agency, improved readability, and clear information about related public comment periods. GovPulse wasn’t the only project to create an innovative tool based on the Federal Register XML release, though it has been the most successful. FedThread, created at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy, was a collaborative annotation tool. (It was discontinued in 2011.) And FederalRegisterWatch.com by Brett Killins provides customized email updates as search queries match new entries published in the Register.17

What happened with EDGAR and the Federal Register is happening with all of the most important government databases (both in the United States and abroad): actors in the private sector are stepping up to empower the public through not merely online access to government publications — we’ve had that since the ’90s — but through a digital transformation of government data into completely new tools.

* * *

Today’s thriving community of open government applications and developers was a decade away when Malamud was starting to define the open government data movement. And while 2009 was the year that government agencies began to widely participate in the open government data movement, we have to go back a few years to see how we got there.

From 1996 to 2004, while technology was rapidly advancing, entrepreneurship in open government continued. Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute, established already in 1992, expanded its website’s collection of primary legal documents to support research and make the law more accessible. The Center for Responsive Politics’s website OpenSecrets.org launched after the 1996 elections. OpenSecrets takes campaign contribution records published by the Federal Election Commission (and today other records as well), then significantly cleans up the data, analyzes it, and publishes it in a form that is accessible to journalists and the public at large to track money’s influence on elections. These are no doubt the longest running open government technology projects.

Entrepreneurship in government transparency was beginning in municipal and state governments around this time. Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley was facing one of the highest crime rates in the country, high taxes, and an under-performing government. He created CitiStat in 1999, an internal process of using metrics to create accountability within his government. The city’s information technology staff became a central part of the accountability system, and by 2003 CityStat’s information technology infrastructure was used to create a public facing website of city operational statistics.18 The CitiStat program and website were replicated in other state and local governments: Maryland’s StateStat launched in 200719, and New York City’s NYCStat launched in 200820 Although CitiStat, StateStat, and NYCStat focused on performance reports and metrics rather than raw underlying data, they proved through practice that data was valuable to keeping governments productive and accountable.

Putting a spin on this idea, the Washington, D.C. government chief technology officer Vivek Kundra created the D.C. Data Catalog at data.dc.gov in 2007, the purpose of which was to spur innovation by providing the public with raw data held by the D.C. government. (Kundra would soon be appointed as the federal chief information officer and would lead the creation of Data.gov.)

But for technologists in the private sector, the call to action came less from open government advocates or new government programs but rather from the infusion of “Web 2.0” and “mashups” in the grassroots digital campaigning of the 2004 presidential elections, especially in the Howard Dean campaign. Independent developers supporting the Dean campaign specialized the open source content management system Drupal for political campaigns, making CivicSpace (now CiviCRM). The campaign’s novel uses of the Internet and the CivicSpace project in particular were widely publicized. That sent a message, even if no one quite recognized it at the time, that developers have a role to play in the world of civics. It crystallized some vague notion of civic hacking (see Chapter 2 for a definition). By the next election bloggers were playing a serious role as part of the news media, and new yearly conferences including the Personal Democracy Forum began giving political technology legitimacy.

Michael Schudson, a professor in the Columbia Journalism School, wrote,

It is not only that the techies see themselves as part of a movement; it is that they see the technology they love as essentially and almost by nature democratic (but in this I think they are mistaken).21

It’s certainly true that we techies see technology as having a unique role to play.

Separately but around the same time as the rise of the Internet in politics, GPS navigation devices were starting to become popular. GPS is one of the earliest and yet most successful examples of government-as-a-platform, a concept recently promoted by Tim O’Reilly (the computer book publisher and also, in full disclosure, an investor in my company POPVOX). GPS is a signal sent by U.S. government satellites, but it had limited value until the end of the federal government’s intentional degradation of GPS signals for civilian use in 2000. Today, use of this digital government service is ubiquitous, and it is often combined with data from the Census Bureau on the nation’s roads and the U.S. Geological Survey’s satellite imagery and terrain data to create maps. Early applications in the modern open data movement were crime maps based on local police data (Adrian Holovaty’s chicagocrime.com in 2005 was one of the first Google Maps mashups) and tools to navigate public transportation. Public transportation remains a popular subject for developers.22

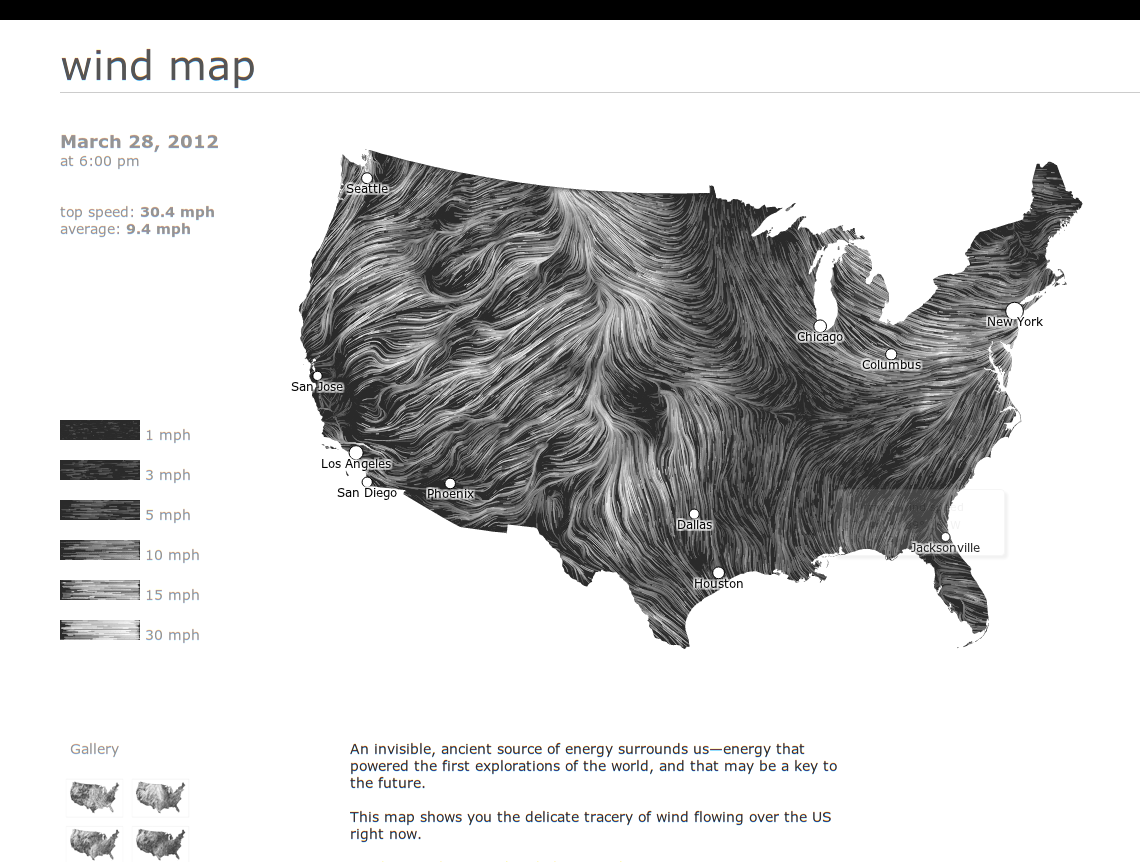

But building products on top of government data is not new, it is only more recognized now. For as long as there has been the modern weather report there has been business around government-produced information. The National Weather Service’s director of strategic planning and policy, Edward Johnson, told me in 2009, “We make an enormous amount of data available on a real time immediate basis that flows out into the U.S. economy.” Both their free-of-charge data and specialized high-reliability and high-bandwidth services (set up on a limited cost-recovery basis) are a crucial foundation for daily weather programming and weather warnings in newspapers and on television. (For a new use of weather data, see Figure 2.) So while much of the open government and open government data movements focus on using that openness to keep a close watch on our government, it is by no means the only use of government data.

Environmental, weather, and occupational safety data have obvious practical consequences for public health. Records of mine safety inspections came to focus in 2010 after the explosion in the Massey Energy mine in West Virginia, the largest coal-mining disaster in 40 years in the country. Because there was an active mine-safety beat reporter covering the area, it stands to reason that the disaster might have been averted had the safety inspection documents submitted by Massey to the Mine Safety and Health Administration been made thoroughly available to the public as they were produced.23

Local data helps neighborhood organizations make practical decisions (see section 3.3).

Government data contributes to the national economy, helps consumers be more informed, and makes our own government more efficient. By empowering citizens to perform their own market oversight, for instance, we reduce the need for regulations and the bureaucracy that regulations create.24 The business of government data is well established. The business world relies on XML corporate disclosures from the Securities and Exchange Commission that keep investors informed. The majority of Freedom of Information Act requests is in fact made for commercial purposes, such as competitive research.25 The private sector has long known the value of government-produced information, though treating government as a platform was only coined “Gov 2.0” recently.26

Information is a crucial driving force in innovation and is a unique kind of resource, a so-called “public good,” because consumption of information by one individual does not reduce the availability of information for others. This is why the benefit of information can extend far beyond its initial purpose. Governments as major producers of information are therefore in a strong position to spur innovation by promoting open government data.

As technologists in the early 2000’s were getting involved in politics and creating added value on top of digital government services, a much broader technological change was happening in other fields: the advent of Big Data. Dana Boyd and Kate Crawford (2011)27 described Big Data:

The era of Big Data has begun. Computer scientists, physicists, economists, mathematicians, political scientists, bio-informaticists, sociologists, and many others are clamoring for access to the massive quantities of information produced by and about people, things, and their interactions . . .

Big Data not only refers to very large data sets and the tools and procedures used to manipulate and analyze them, but also to a computational turn in thought and research (Burkholder 1992). Just as Ford changed the way we made cars — and then transformed work itself — Big Data has emerged a system of knowledge that is already changing the objects of knowledge, while also having the power to inform how we understand human networks and community . . .

It re-frames key questions about the constitution of knowledge, the processes of research, how we should engage with information, and the nature and the categorization of reality. Just as du Gay and Pryke note that ‘accounting tools...do not simply aid the measurement of economic activity, they shape the reality they measure’ (2002, pp. 12-13), so Big Data stakes out new terrains of objects, methods of knowing, and definitions of social life.

In other words, Big Data has two parts: 1) Big Data is data at scale, with millions of records and gigabytes of data, and 2) Big Data changes the way we think about the subject of the data in a significant way.

Open government data is the Big Data concept applied to open government. First, it is the application of government records at scale. Open government data applications make use of whole datasets to provide comprehensive coverage of information: not one SEC record but the whole database, not one agency’s rule-makings but the whole Federal Register, not the weather in your neighborhood but the whether anywhere in the country. A larger database with a wider range of information makes an application useful to a wider range of users, and it provides something for the long-tail of individuals with fringe interests who might not otherwise be served. There are thousands of bills being considered in Congress at any given time, and there is something for everyone — from agriculture to medicine and hundreds of issue areas in between. Data at scale also gives perspective. When a journalist reports that a certain Member of Congress has missed 10% of votes, is it a lot or a little? When plain-language advocates call for simplified language in laws, how can you know whether it makes sense without being able to survey a wide cross-section of law?

And then there is the second part of the definition of Big Data. Open government data differs from conventional open government policies in the same way that “data” differs from “information” or “knowledge.” The conventional open government movement relies on the disclosure of records, such as who is paying who, who is meeting with who, and records of government decisions and findings. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and at the state level freedom of information laws (FOIL) are laws that grant the public access to these sorts of government records. Each FOIA/FOIL request is for a particular record. FOIA/FOIL create a direct relationship between the government and the information consumer.

Contrast this with the role of a journalist who distills wider-reaching knowledge for their information consumers, their readers. Journalists are mediators. Take the case of the 2002 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. The 14-part series on the deaths of children neglected by D.C. social services was a transformation of thousands of government records into a new form more useful and informative for The Washington Post’s readers.28 The series could not have been told without access to government records at scale. And conversely, the value of those government records came from reporters’ skills in turning the records, and of course interviews, into something pointed, understandable, and actionable for their readers. Put another way, the knowledge that Post’s readers gained from the 14-part series could not have been FOIA’d from the government directly. The knowledge came from skilled synthesis by mediators who took raw data materials and produced an information product for consumers.

I think we tend to forget that mediators have always played a central role in the dissemination of information. Some of the most technologically savvy mediators today are the nonprofit advocacy organizations, who through email blasts keep their members informed of complex policy issues. The iconic mediators of the 20th century were the radio and television anchors. Before that was the penny press, one-cent newspapers starting in 1830’s New York that began the modern sort of advertising-fueled and politically neutral journalism, and going earlier the advocacy journalism leading up to the Revolutionary War.

Perhaps FOIA/FOIL never really served mediators well. Mediators need wide swaths of information that cross-cut individual events in time. The mediator analyzes the information for trends, distills the information into key points, and presents something useful to the information consumer that is very different from the source materials. And so it’s not surprising that since FOIA/FOIL provide access to such narrow windows into government decision-making that journalists would make up only around six percent of FOIA requests.29

Open government data is the type of disclosure suited for mediators, whether they be journalists, programmers, statisticians, or designers, who transform the originally disclosed bytes into something very different and of a greater value to a consumer. And so it is ironic that open government data faces resistance in government because open government data is not the future of e-government innovation: it is a new technological approach to the sort of information dissemination that has always existed. The best argument for open government data that I’ve heard is that this is how consumers already get their information, although they don’t see it in those terms. Whether you are a politician who wants to shape the debate or an administrator who wants to reduce the cost of processing FOIA requests, you have to show up to the party to have the chance to participate, and that party has always been the information mediators. As Derek Willis of The New York Times put it to me, it’s as simple as this: people go to Google to find information, so governments ought to make sure their information is findable on Google if anyone is going to see it. That means more than making sure your website is indexed. It means working with all of the “engines of information,” as Willis put it. The presumption of openness established by FOIA/FOIL is still important for open government, of course, but FOIA/FOIL stop short of guiding how government data can be disclosed in a way that promotes this sort of mediation.

The second part of the definition of Big Data is that the scale changes the way the subject of the data is understood, and that is true here. Open government data has changed the way the open government movement operates and the way individuals interface with government. It has broadened the set of professions that can participate in open government to any profession that can tell a story by transforming raw data into something new. And it has engaged more lay individuals in government transparency, and in government and civics more broadly, through the novel applications of government data that have been created by these professionals that make government more accessible and engaging.

In the rest of this chapter, which fills in the history of the open government data movement, and in the subsequent chapters, keep in mind the two fundamental qualities of open government data: scale and transformation.

* * *

I’ve never particularly liked politics. It’s all the antagonism that really gets to me, and the way political parties try to advance their position for the next election at the expense of public policy. I do like civics and legal theory, and that’s probably how I ended up in a class my freshman year at Princeton in 2001 called “The Speech is a Machine.”30 “[N]ow that software is simultaneously speech and a machine,” read the syllabus, “parts of the law that never clashed before now contradict each other.” Software code is speech in the sense that it is expressive. Code can be elegant and creative, both in the problem it solves and in the way it solves it, giving it potential protections under the First Amendment. And software is a machine in the more familiar sense, because software does something, bringing it under the regulations covering trade, patents, and actions.

The class was timely, right in the middle of the hay-day of music sharing over peer-to-peer networks. In class we staged a mock court case that hinged on whether the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) could prevent playing DVDs you’ve just purchased — and out of class my professor Andrew Appel and his colleague Ed Felten were being threatened by the music recording industry over publishing their research on digital watermarks, a technology in development at the time to thwart unauthorized copying of digital files. And though the recording industry didn’t say it outright, everyone knew that the threat was backed by the plausible claim that publishing the research was made illegal by the DMCA (even though the recording industry had invited the researchers to conduct the study in the first place!).31 Peer-to-peer networks like Napster began getting shut down several months later by litigation from the recording industry — the recording industry thought the software crossed over the speech-machine divide. In response, students on college campuses began building their own small sharing networks with surprisingly advanced infrastructure (such as scanning publicly shared folders) — and then the first suits against college students came for running sharing networks. One suit was against a Princeton sophomore in 2003. It felt harsh, and personal, and it motivated many of us to consider how our technology expertise could be used in the public sphere.

The class was the first time that I saw that lawmaking was a dynamic process with interests competing for the best policy for themselves. It seemed to me that in the case of the DMCA, Members of Congress had either failed to understand the DMCA or simply caved to the business interests that lobbied for protection for their antiquated industry. But why didn’t the American public hold Congress accountable for a patently wrong decision? From class I was familiar with the website THOMAS.gov, the legislative resource created after the Contract with America. THOMAS is a comprehensive public record, but the details make it daunting to navigate for anyone but legislative professionals.

Looking back, I can think of three other services that I knew of that inspired me to dig into government’s Big Data. First was the Center for Responsive Politics’s campaign finance website OpenSecrets.org, which I learned of from working on the student newspaper. Second, in the late 1990s I had subscribed to email updates for the votes of my Members of Congress through a free service of America Online and Capitol Advantage (now a part of CQ Roll Call). So I knew that there were other useful ways besides THOMAS to present the truly vast amount of information processed by Congress and to help the public track the bills that interested them. While I thought of both OpenSecrets and the votes service as a part of Web 1.0, the third service I could relate to on a more personal level: it was an open source project out of MIT’s Media Lab. The project aimed to track the potential conflicts of interest of Members of Congress, and it was at the same time a parody of a project at DARPA, the research agency of the Department of Defense, that would mine large databases of information about the public for terror threats. DARPA’s project was ominously named Total Information Awareness, MIT’s project Government Information Awareness.32 The question in my mind, as in the minds of the MIT developers, was with better tools could the public hold Congress accountable?

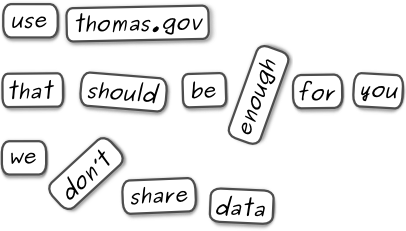

At the same time I felt insulted by the government. The Library of Congress, which runs THOMAS, obviously had a database of all of the public information that went into powering THOMAS. But the Library did not make the database, in raw form, available to the public to innovate with. The difference is like being given refrigerator poetry magnets that have been glued into a pre-written sonnet. You can appreciate the sonnet, sure, but the glue has limited the obvious potential that comes from being able to rearrange the pieces and discover new meaning. Data is the same way. THOMAS (the sonnet) continues to be a vital resource for the American public even largely unchanged 15 years after it was created, but there is potential locked away when the information behind THOMAS (the poetry pieces) cannot be re-purposed or transformed into other applications.

By withholding their database from the public, Congress and the Library of Congress seemed to be saying they should be the sole source of information on what Congress was doing. That’s not only unfortunate, it is un-American. (I’ve been asking the Library to share its data since 2001, more than 10 years ago now. In fact, in 2009 an Act of Congress — or a small part of an act that I worked on with Rep. Mike Honda’s office33 — encouraged the Library to move forward with this. After that stalled, Rep. Bill Foster introduced a bill just on this point in 2010. Still no progress. The real hold-up is that the Library’s law division does not see publishing data as a part of its mandate authorized by Congress, and getting both the House and the Senate to agree on updating the Library’s mandate is slow going. In response to the open government data movement, the current House Republican leadership promised to make available the House Clerk’s legislative database, and some progress on that has been made with the launch of docs.house.gov in January 2012.)

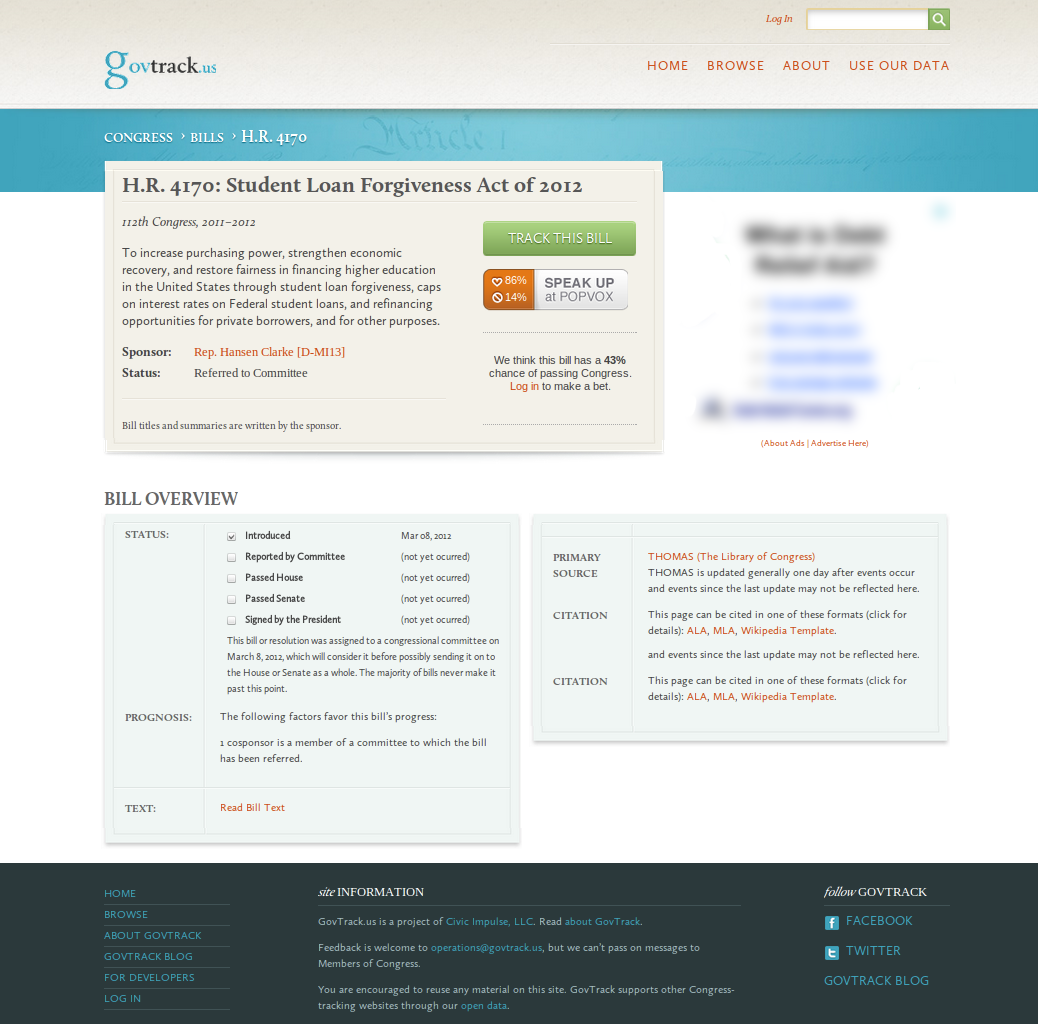

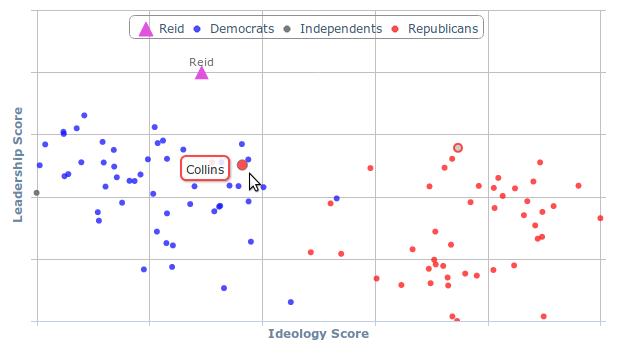

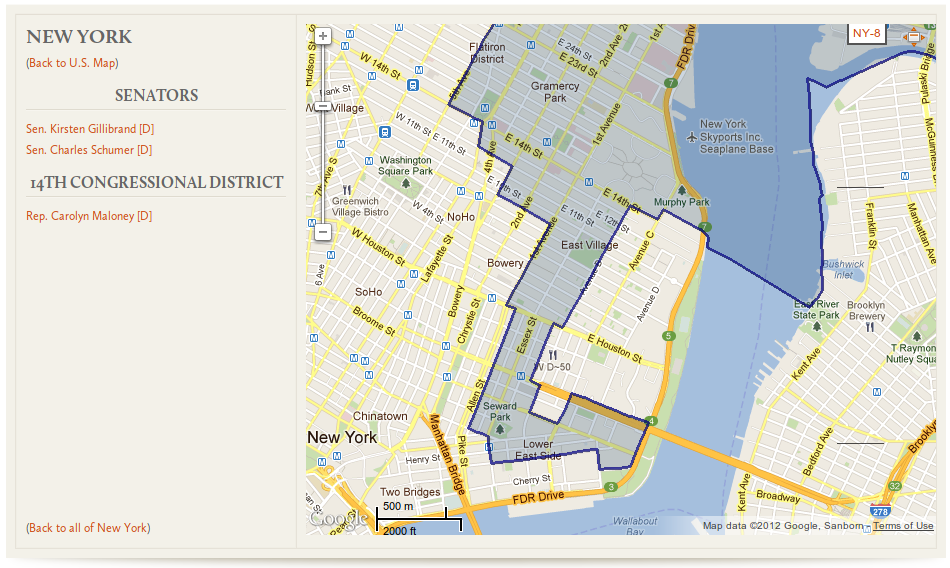

It was several years later in 2004 that I finally finished and launched GovTrack.us, a website that tracks the activities of the U.S. Congress (Figure 4). It was one of the first websites world-wide to offer comprehensive parliamentary tracking for free and with the intention to be used by everyday citizens. Most of the information on the site can be found elsewhere, but in so many different places and in formats that they are hardly useful to the American public. For instance, voting records are found for the House of Representatives on the House’s website and for the Senate on the Senate’s website. The status of legislation is listed on THOMAS, but schedules of hearings to discuss the legislation are scattered around several dozen Congressional committee websites. With many small programs GovTrack “screen-scrapes” all of these websites, normalizes the information, and creates a large database of Congressional information. The legislative database is the first part of GovTrack. With the data assembled, i.e. the refrigerator poetry pieces unglued, I was able to create what you see when you visit GovTrack.us: the status of legislation, RSS feeds for the activities of Congress, interactive maps of Congressional districts, and change-tracking for the text of bills. The website is ad-supported.34

Being able to read the bill that Congress is about to pass is a little like the experience of being in the capital for the first time and seeing the Declaration of Independence under glass at the National Archives. Our nation isn’t abstract. There it is on my screen right there. Or, there it is in my inbox. GovTrack is able to offer a unique view into Congress, giving the public a deeper understanding of how our government works and getting citizens more engaged. So I like to think that when a bill number — like H.R. 3200 — is said on the air of a late night TV show, such as The Daily Show (Figure 5) or Late Night with Jimmy Fallon35, that I might have contributed to the greater public consciousness of the legislative process. And at this point, civic education, rather than accountability, is GovTrack’s primary goal.

* * *

Toward the end of 2005 I got an email from Micah Sifry who the year before started the Personal Democracy Forum, a conference at the intersection of technology and politics. He wrote, “I’m doing some consulting for a new organization that is seeking to open up the system to more scrutiny, and it would be great if we could do this in a way that maximizes the network effects.” I didn’t know what “network effects” meant or what he was getting at at the time, but this was the beginning of today’s dominant organization in government transparency advocacy: the Sunlight Foundation. Ellen Miller, who had run the Center for Responsive Politics, had met Mike Klein, a lawyer and entrepreneur who discovered the value of commercial real estate data, and the two formed this new organization that would combine technology, policy, investigative reporting, and organizing. Sifry’s vision of leveraging “network effects” came to fruition in many ways, including the annual Transparency Camp conference started by Sunlight’s labs director, Clay Johnson. (Clay got his start in political technology by working as the lead programmer for the Howard Dean Campaign, bringing that part of this story full circle.)

Sunlight was primarily a grant-making institution at first. But a small project that began in 2006 changed that. That year was a mid-term election year in which a series of scandals involving Republican congressman threw the majority to the Democrats. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who on election night became the presumptive next Speaker of the House, announced that the next two years would be “the most honest, most open, and most ethical Congress in history.”36 It was in this climate of cleaning house and standing up to corruption that John Wonderlich, then a telemarketing manager in Pittsburgh, posted a note on DailyKos (a left-leaning blog) recruiting help for a citizen journalism project. The goal of this project, the Congressional Committees Project, was to assign one person, a regular citizen, to each committee and subcommittee in Congress. That person would follow the committee closely and report back what the committee was doing to the group in a non-partisan way. The project was all set to begin, just waiting for Congress to come back from winter recess, when the “new media”37 staffer for Pelosi contacted Wonderlich and asked to have the group collect some feedback about how Congress could be more transparent in the coming years by making better use of technology. The request from Pelosi’s office ended the committees project as the telemarketer from Pittsburgh shifted his attention to leading what became the Open House Project, a formal response to Pelosi’s request.

The Open House Project, sponsored by the Sunlight Foundation, issued a report on May 8, 2007 at a press conference held in the basement of the U.S. Capitol building and in front of C-SPAN cameras. After many months of deliberation among a wide group of open government advocates, Wonderlich, Miller, myself, and several others presented the report recommending technology-related improvements to congressional transparency in the areas of legislative data, committee transparency, preservation of information, relaxing antiquated franking restrictions that kept congressmen off of social networks, ensuring the Congressional Record reflected accurate information, access to the press galleries, improving disclosure reporting, access to Congressional video, coordinating web standards, and sharing with the public the reports of Congress’s research arm, the Congressional Research Service.

One of the project’s first successes was how its recommendations on franking, written by David All and Paul Blumenthal, influenced the outcome of the 2008 House and Senate rules changes that allowed Members to connect with their constituents through social media38. It is hard to remember it, but for many years Congress’s internal rules actually forbade Members of Congress from participating in social networks like Facebook, stifling new ways Members of Congress and their constituents could stay in touch. And it wasn’t even clear to transparency advocates that they even should, since participation in one network might constitute an endorsement of a particular business. Endorsements then and now are rightly forbidden by congressional rules. But times quickly changed, congressional rules changed, and as it turned out, social media in government became much more of a public relations tool rather than a way to have a genuine dialog with the public.

Most of the remaining recommendations sadly still remain on the movement’s wish list, but the project was crucially important because it became a cornerstone of the policy work of the Sunlight Foundation. Wonderlich is now Sunlight’s policy director and is a registered lobbyist.

Following the Open House Project in 2007 Carl Malamud — who had liberated the SEC data in the ’90s — lead a workshop that wrote the “8 Principles of Open Government Data.” The 8 Principles gave us consensus on general principles that guide how governments should release data to the public, including that the data should be timely, in a machine processable format, and not restricted by license agreements (for the full principles see Chapter 5). That workshop not only crystallized ideas but also started to form a somewhat cohesive movement of individuals interested in government and data, picking up where the Open House Project left off.

Then came 2009, the year of the first two Transparency Camp conferences and Clay Johnson’s announcement that we had become a movement. It was also the year that open government data started to make visible strides actually inside government. I mentioned the improvements to the Federal Register already. A bulk data download from the GPO of the Code of Federal Regulations followed shortly after the Federal Register. We also saw the Senate start publishing votes in XML format, again a change that allows the private sector to create new applications around the data. (They followed six years behind the House. The two chambers of Congress operate entirely separately so the two chambers of course use completely different schema and IDs for Members of Congress, and I don’t know of any plan to unify them.) And the House began publishing its spending data electronically (more on that in section 5.2).

Since the House has published bulk data for the United States Code for some time, which Cornell’s Legal Information Institute has used to create the de facto online source to read the U.S. Code, a substantial part of federal law is available online and in a form useful to build new applications on. The judiciary branch of government is the remaining sore thumb in creating open access to federal law. More on that in section 3.2.

Data.gov, the IT spending dashboard, and the Open Government Directive39 which called for innovation in transparency, participation, and collaboration, all were published in 2009. To my surprise, the Directive addressed nearly all of the 8 Principles of Open Government Data, and essentially added two of its own: being pro-active about data release and creating accountability by designating an official responsible for data quality.40 But the White House projects of 2009 were about more than just transparency theory. Vivek Kundra, the first U.S. chief information officer and the driving force behind Data.gov, claimed the IT spending dashboard saved taxpayers $3 billion and accelerated other programs by giving government administrators better access to performance measures of information technology projects.41

Despite the Directive’s call for change, these projects have been generally criticized on two fronts. First, the apparent success of Data.gov has largely ridden on the inclusion of data sets that had already been available to the public. My favorite data set included early on in Data.gov was Federal Aviation Administration flight on-time statistics, which has been released in some form since 200342. A fellow coder Josh Sulkin and I built FlyOnTime.us, which used historical flight on-time statistics and weather data from the National Weather Service to predict future delays, for instance to help fliers make better decisions about connecting flights. (FlightStats.com, a commercial website, and FlightCaster.com, a startup that raised nearly $1M, independently had similar ideas.)

The second line of criticism has been that whatever new and supposedly “high value” data that was released following the Directive was not very interesting for government transparency. The highest rated dataset on Data.gov now is “Active Mines and Mineral Plants in the US” from the U.S. Geological Survey. Environmental and weather data comprise a large part of the data catalog. These are certainly important data sets for their connection to public safety. If journalists get a deeper perspective on mine safety and if that saves lives, then it would be hard to name an even more important data set. But the datasets don’t fulfill the promise of transparency. For that, we’re looking for open access to administrative records, records that tell us how decisions were made and that help the public stay informed about agency activity. It’s really no surprise that Data.gov has excelled in the sort of data sets it has since the Environmental Protection Agency and especially the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the Department of Commerce, the original source of most weather reports, have been leading the public dissemination of raw government data since well before there was an open government data movement.

Alon Peled, a professor of political science and public administration, explained in a review of Data.gov why federal agencies may have resisted open data:

Open Data architects failed to consider that datasets are valuable assets which agencies labor hard to create, and use as bargaining chips in interagency trade, and are therefore reluctant to surrender these prized information assets for free.43

Peled’s point highlights the need for open government advocates to stay grounded in reality.

Still, the benefit of Data.gov may be less in the catalog itself and more in the standards it sets for federal agencies and the cultural change it symbolizes. Harlan Yu pointed to what he says is under-appreciated infrastructure:

There’s a Data.gov manual that formally documents and teaches this process. Each agency has a lead Data.gov point-of-contact, who’s responsible for identifying publishable datasets and for ensuring that when data is published, it meets information quality guidelines. Each dataset needs to be published with a well-defined set of common metadata fields, so that it can be organized and searched. Moreover, thanks to Data.gov, all the data is funneled through at least five stages of intermediate review—including national security and privacy reviews—before final approval and publication. That process isn’t quick, but it does help ensure that key goals are satisfied.44

Health & Human Services (HHS) stands out as one of the few federal departments that hadn’t had a prior commitment to open data that has strongly embraced the Directive, now having released to the public data sets including FDA drug labeling and recalls, Medicare and Medicaid aggregate statistics, and national health care spending estimates, among others. HHS has been actively promoting reuse of their data with an Apps Expo, contests, and code-a-thons.45

At the municipal level, strong open data initiatives have been under way in San Francisco, Chicago46, Boston, and New York City47.

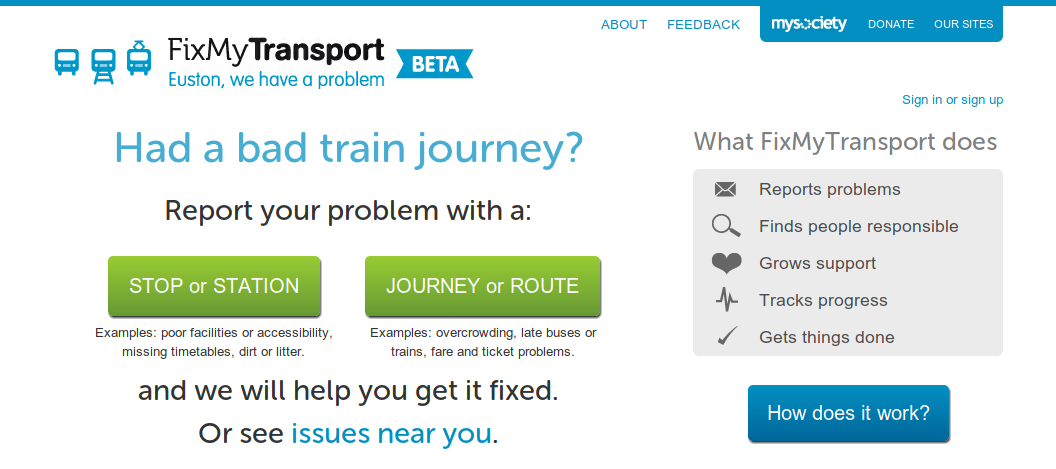

Data.gov spurred a world-wide movement of data.gov. catalogues, some of them better than our own here. Data.gov.uk, for one, has innovated in the application of Semantic Web technology to establish connections between datasets from different agencies. There now are hundreds more Data.gov’s in states and municipalities in the United States and in countries throughout the world.48 The Open Government Partnership, launched in mid 2011, is a multi-government effort to advance parallel transparency reforms in participating countries, focusing on disclosure, citizen participation, integrity, and technology.49 (I would be remiss at this point not to mention TheyWorkForYou.com and the non-profit behind it, mySociety, which had by this point long been leading the technology-meets-civics cause across the pond. TheyWorkForYou is much like GovTrack for the U.K. parliament and was developed independently around the same time. More about them in section 3.4.)

The Directive also called for innovation in citizen participation and collaboration with government, yet another new area of the open government movement. Law professor Beth Simone Noveck led this aspect of the Directive during her time as the U.S. deputy chief technology officer for open government (2009–2011) — she had previously invented Peer to Patent, which connects the U.S. patent office with expert volunteers to make the patent review process more informed. The White House’s We The People website at whitehouse.gov/petitions, launched in September 2011, fulfills some of the promises of participation. The site facilitates petitions which the White House pledges to respond to once a threshold of signatures is reached, currently 25,000 in 30 days.

The U.K.’s prime minister office began a similar system called e-petitions in 2007. In the current version at epetitions.direct.gov.uk, it takes 100,000 signatures to bring up an issue in the House of Commons. On August 11, 2011, a petition to cut social security benefits from rioters reached the threshold and was referred to a House of Commons committee, but the parliament has been out of session recently and has not formally debated the e-petition yet.50 Other participatory projects are occurring throughout the world. The Palestinian Prime Minister used Facebook to collect nominations for his cabinet, and the New York City council empowered neighborhood assemblies to determine local infrastructure projects.51 To Noveck, the benefit of applying technology to participating and collaboration is in making government smarter, policy better, and citizens motivated.

But for all of these promises we should remember to treat technology as mere technology. Governance is a social problem, not a technological problem. Michael Schudson, the journalism professor, wrote about perspective on the role of technology:

There is reason to be suspicious of the notion of technological revolutions. The printing press did not usher in democracy — or, if it did, it took its good-natured time! ... Later, the telegraph was said to have been the center of a communications revolution. But at first the telegraph — that is, the electronic telegraph as we know it — was a relatively minor advance on the ‘optical telegraph,’ versions of which had existed for two thousand years. [I]t required the spirit of entrepreneurship at the new penny papers ... to take advantage of the telegraph for news transmission. ... One needs not only technologies for a revolution, but also people who can recognize their worth.52

We’re not going to see technology usher in some new form of direct government by the people. Nor would we necessarily want it. Technology doesn’t make direct democracy any more practical now than in ancient times. Think about how you would feel if after your long work week your civic homework was to read a 100-page bill proposed by a stranger three states over. Not fun. That’s exactly why we elect people to do that work for us. The survey in Stealth Democracy found that most people wanted a sort of indirect democracy, like what we actually have.53 So as Schudson wrote, there is something democratic about technology but it is no silver bullet. It takes persistence and creativity to put technology to work in our civic lives.

* * *

Movements are guided by principles. Our principles are that data is a public good, that value comes from transformation, that government is a platform, and that process is a legitimate policy question. Those are the sort of principles about how the world should be. There are also principles that help us understand how the world is now, and they tend to turn into buzz words: Big Data, Web 2.0, Gov 2.0, mediation, transformation, open, participation, and collaboration. Buzz words or not, these principles highlight differences we didn’t notice before so that we can better draw analogies, and from there make better decisions. Is your website’s goal to “democratize data” or to “shine light” on corruption? If it’s the former, you may learn from such and such past examples of democratizing data, but if it’s the latter you may want to follow in the paths of these other projects. And so the remaining chapters are made up of all sorts of new terminology — these are all of the principles of the open government data movement.

2. Civic Hacking By Example

1. The Hacker Communities

“Hacking” has come to mean two quite different things. One is breaking into a computer system. That is the popular meaning, but not the one relevant to open data. The other meaning is a source of pride among programmers and geeks at large, and it means perverting something’s original purpose to solve a problem. Rube Goldberg machines are hacks. The use of the lunar lander to bring the Apollo 13 crew home was a hack. The first computer games were hacks (computers were not meant for games). Open government applications are usually hacks because they are based on information that had been published by the government for reasons other than the problem the open government hacker is trying to solve.

Civic hacking is a creative, often technological approach to solving civic problems.54 These civic problems run the gamut from voter registration and public education to helping consumers evaluate financial advisors.55 Civic hackers can be programmers, designers, or anyone willing to get their hands dirty. Some civic hackers are employed by nonprofits, such as Code for America or OpenPlans. Others work for innovative for-profit companies, such as the geospacial software provider Azavea in Philadelphia. Others are civic hackers only by night.

Civic hackers often meet to work on problems collaboratively at “hackathons,” one- or two-day community-run events typically held around a particular theme. While solving real problems often takes years of deliberate effort, these short events strengthen the connections among local hackers and help orient them to the complexities of civic problems. That is especially true when subject matter experts, especially those in government, participate. At a hackathon I ran in Philadelphia in 2009, two analysts from the New Jersey State Police worked over the course of two days with five volunteer programmers to develop a visualization tool for gang activity tracked by the police department.56 On that same day, nearly 200 developers across the country were participating in the Sunlight Foundation’s call for a Great American Hackathon.57 On December 3, 2011 hackathons were held in some 30 cities world-wide for International Open Data Day.58 There have been many, many hackathons in between and since.

Obviously our little gang statistics website in 2009 did not solve the problem of gang violence. That was never the point. Everyone knew that follow-through after the event just to finish up the website would be difficult, and frankly unlikely. Not every weekend has to solve a problem.

And yet the hacker community is stronger and more effective because of it.

Civic hacking has been spurred by contests (typically called “challenges”) as well. The first, back in 2008, was Apps for Democracy in Washington, D.C. Apps for Democracy put up $20,000 in prizes for applications built using the city government’s newly opened data. iStrategyLabs, which worked with the DC government to create the contest, said that the contest entries — including one mobile app to submit GPS-tagged photos of potholes and other city problems to the city’s 311 service — would have cost the government $2 million to build, 40 times the amount of money the DC government actually spent on encouraging the apps to be created (including overhead).59 (The D.C. government chief technology officer, who led the city government’s side of the contest, was Vivek Kundra, who also created the D.C. Data Catalog the year before and became the federal chief information officer the year after.)

After the Obama Administration’s Open Government Directive, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) really stepped up to the call for engaging with entrepreneurs to turn government data into value for the public. HealthData.gov currently lists 249 data sets and tools from HHS. Healthcare IT News reported in early 2012 about two recent challenge winners:

The winning apps . . . were each awarded $20,000 by [HHS’s] Office for the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). They are:

Ask Dory! Submitted by Chintan Patel, Sharib Khan, MD, and Aamir Hussain of Applied Informatics, LLC, the app helps patients find information about clinical trials for cancer and other diseases, integrating data from ClinicalTrials.gov and making use of an entropy-based, decision-tree algorithm. . . .

My Cancer Genome. Submitted by Mia Levy, MD, of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, the app provides therapeutic options based on the individual patient’s tumor gene mutations, making use of the NCI’s physician data query clinical trial registry data set and information on genes being evaluated in therapeutic clinical trials. The app is in operation at MyCancerGenome.org.60

These ideas are extraordinary, and often unpredictable from the data they chose to use. HHS is now heading into its third Health Data Palooza in 2012, an annual conference centered on public-private partnerships that have created innovation in public health using data and technology. (Todd Park, HHS’s chief technology officer who launched these initiatives, became the federal chief technology officer in 2012.)

In the case of Apps for Democracy, iStrategyLabs called the $2 million of value created by the contest a 40x “return on investment.” Viewed in this way apps contests are bound to be considered failures. Even if $2 million of man-hours were put into contest entries, most entries don’t yield lasting, useful products. Like hackathons, contest entries don’t usually solve problems.

And yet, the hacking community — and the public at large — is better for it. Not all apps submitted to a contest have to work for the public to benefit, as long as one app leads to a better app a few years later, and maybe from that a whole company that goes on to provide services over the long haul. Unfortunately, I don’t know if this has already happened in health data. There have been too many contests and too many entries for me to have followed Health 2.0 closely so far, but I’ll find out for the next edition of this book! It has happened in other fields, at least. In Chapter 1 Federal Register 2.0 was discussed, a project that came out of the Sunlight Foundation contest Apps for America. We’re only a couple of years into contests. The creative juices are only just now really flowing.

If you are new to civic hacking and want to get involved, start by looking at the work of Code for America (codeforamerica.org). They provide fellowships for civic hackers to work within city governments to help the city work better with technology. Their new Brigade program (brigade.codeforamerica.org) will help you find a project to work on that will help the people of the city you live in. And be on the lookout for civic-themed hackathons in your area on Meetup.com.

2. Visualizing Metro Ridership

Ever since my move to Washington, D.C. I have been obsessed with the Metro system, our subway. In this section we’ll create a simple visualization of the growth of D.C. neighborhoods using historical ridership data at Metro rail stations. While open government data applications come in many forms, they often share a common set of methodological practices: acquiring the data, cleaning it up, transforming it into an app or infographic or some other presentation, and then sharing the progress with others. Acquiring data sounds easy. It’s often not. Each of these four steps can bring its own challenges, and we will walk through some of these challenges here.

If you are a would-be civic hacker, look out for some of the data processing tricks that follow. If you are a data publisher in government, look out for simple things you can do when you publish your data that can go a long way toward empowering the public to make better use of it.

The neighborhood that I live in, Columbia Heights, has undergone significant revitalization since its Metro station opened in 1999, and especially in the last several years. It has become one of the most economically and ethnically diverse areas of the city. I suspected, going into this example, that Metro ridership would reflect the growth of the community here. The problem I hope to solve is to answer questions about my neighborhood such as how it has changed, when has it changed, and whether the locations of new transit stations worked out well for the community.

Step 1: Get the Data

The first step in any application built around government data is to acquire the data. In this example acquiring the data is straightforward. The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) makes a good amount of data on its services available to the public. It even has a live API that provides rail station and bus stop information including arrival time predictions (which others have used in mobile apps). For this project, however, we need historical data.

WMATA has recorded average weekday passenger boardings by Metro rail station yearly since 1977, the first full year of operation for the subway-surface rail lines. Twenty-four stations were operational that year. The last line to finish construction, the Green Line, started operation in 1991. Historical ridership information by station is made available by WMATA in a PDF. PDFs are great to read, but we’ll see that they are pretty bad for sharing data with civic hackers. The location of the PDF “Metrorail Passenger Surveys: Average Weekday Passenger Boardings” is given in the footnote at the end of this sentence.61

If you are following along at home, download the PDF. Look it over to get a sense of global patterns. Is Metro ridership increasing over time? The final row of the table has total Metro ridership across all stations. It’s easy to see ridership has increased about five times over the past 30 years. But if you wanted to use the information in a serious way, such as to make a simple line graph of total ridership, you would run into a problem for 2008. The PDF actually reads “######” as the total ridership for 2008. (See Figure 6.) Hash marks are what many spreadsheet applications write out when the actual number can’t fit within the size of the cell. WMATA had the number, but it got replaced with hash marks when their spreadsheet was printed as a PDF.

If you want to make that graph, you can of course sum up the individual station ridership values in the column above it. Type 86 numbers into a calculator. Not hard, but you risk making a mistake. Wouldn’t it be nice to have the table in a spreadsheet program such as Microsoft Excel! That would make finding the 2008 value a breeze. This is the sort of problem we’ll run into as we get into dissecting the table in more detail next.

The second data set for this project provides latitude-longitude coordinates of all of the rail and bus stops in the WMATA system, which will be useful to plot ridership numbers on a map. WMATA provides this information in Google Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) format, which is a standard created by Google that transit authorities use to supply scheduling information for Google Maps Directions. Download google_transit.zip as well and extract the file stops.txt.62 The data totals 86 MB uncompressed, although we’ll only need a small slice of it.

WMATA, like many transit authorities, requires you to click through a license agreement before accessing the data. The terms are mostly innocuous except one about attribution which reads, “LICENSEE must state in legible bold print on the same page where WMATA Transit Information appears and in close proximity thereto, ‘WMATA Transit information provided on this site is subject to change without notice. For the most current information, please click here.’ ” (To WMATA: You can consider the previous sentence the attribution that is required for the figures displayed later on.) Although attribution is often innocuous, that doesn’t excuse WMATA from violating a core principle of open government data. Governments should not apply licenses to government data (see Chapter 5).

Step 2: Scrub the Data

Government data is rarely in a form that will be useful to your application, if only because your idea is so new that no one thought to format the data for that need. Normalization is the process of adding structure. Even if your source data file is in CSV format (a spreadsheet), you’ll probably have to normalize something about it. Perhaps dollar amounts are entered in an unwieldy way, some with $-signs and some without (you’ll want to take them all out), parenthesis notation for negative numbers (you’ll want to turn these into simple minus signs), and so on. The goal is to get everything into a consistent format so when you get to the interesting programming stage (the “transformation”) you don’t have to worry about the details of the source data encoding as you are programing your application logic. That said, you’re lucky if that is the extent of your normalization work. Normalization often requires a combination of cheap automated tricks and some time consuming manual effort. That was the case here.

WMATA’s historical ridership table in a PDF is great for reading by people, but copying-and-pasting the text of the table from the PDF to a spreadsheet program won’t quite work. I tried it, and you can see the before-and-after result in Figure 7. Copying from PDFs is hit-or-miss. In this case, it’s a bit of a miss: the years, which were supposed to be column headers, are running row after row. Other rows are broken into two, and the names of transit stations that have spaces in their names (that is, they are multiple words) shifts over all of the ridership numbers into the wrong columns. It’s a mess. If a spreadsheet is going to be useful, we need the columns to line up!

At this point, one could clean up the spreadsheet by hand to get all of the numbers in the right place. In this example project, that’s reasonable. But that’s not always going to be possible. The U.S. House of Representatives publishes its expenses as a PDF that is 3,000+ pages long. Imagine copying and then cleaning up 3,000 pages of numbers. It would take a long time.

For the techies, here’s the more intimidating way to deal with problem PDFs. (Non-techies might want to skip the next few paragraphs.) The first thing I did with the PDF was convert it to plain text using a Linux command-line tool. It’s more or less what you’d get from copy-and-paste, but saved straight into a text file. (This is especially useful when you have more than a few pages to copy-and-paste, and the result can be cleaner anyway.) Here’s the command63:

pdftotext -layout historicalridership.pdf

The result is a text file (named historicalridership.txt) which looks conveniently like the PDF. That’s good, because next you’ll need to edit it. Here’s what we got in that file from the pdftotext program:

Nov All Daily Passenger...

Station 1977 1978 1979 ...

Dupont Circle 7,784 10,124 13...

Farragut North 7,950 12,531 12...

Metro Center 10,493 13,704 19...

First, the columns don’t really line up. Half-way through things get shifted over by a few characters. That means we’re not dealing with fixed-width records. Instead, we’ll have to treat the file as delimited by the only character that separates columns: spaces. That leads to the second problem: Spaces not only separate columns, they also are used within the names of multi-word stations. After running into this as a problem later, I came back and put quotes around the station names with spaces in them, knowing that LibreOffice Calc will ignore spaces that are within quotes. So then we have:

Nov All Daily Passenger...

Station 1977 1978 1979 ...

"Dupont Circle" 7,784 10,124 ...

"Farragut North" 7,950 12,531 ...

"Metro Center" 10,493 13,704 ...

After saving the file, I opened it up in LibreOffice Calc. (It’s handy at this point to give the file a .csv extension, otherwise LibreOffice prefers to open it as a word processing document, rather than as a spreadsheet.) It’s easier in LibreOffice Calc to finish off the normalization. LibreOffice Calc asks about how to open it: choose space as the delimiter, the quote as the text delimiter, and turn on “merge delimiters.”

Non-techies, glad to see you again, because you are not out of the woods yet. Even with the columns lining up, there is more clean-up to do in the spreadsheets: Use find-and-replace to delete all of the asterisks in the column headers (the asterisks referred to notes in the footer, but we want the years in the header to be plain numbers), delete the topmost header and bottom-most footer text so that all that’s left is the table header row (the years), the station names and ridership numbers, and the row of total system-wide ridership at the end — we’ll use that to check that the normalization was error-free.

We’re lucky that WMATA provided redundant information in the file. Redundant information is a great way to check that things are going right so far (the same concept is used in core Internet protocols to prevent data loss). The final row of the PDF is the total ridership by year — the sum of the ridership values by station. Since we can’t be too sure that LibreOffice Calc split up the columns correctly, a great double-check is comparing our own column sums with the totals from WMATA. Insert a row above the totals and make LibreOffice compute the sum of the numbers above for each year. (Enter “=SUM(B2:B87)” into the first cell and stretch it across the table to create totals for each column.) The numbers should match the totals already in the file just below it — and they do, until the column for 2008 which I noted earlier was filled with hash marks. It should be a relief to find an error in source data. Source data is never perfect, and if you haven’t found the problem it’ll bite you later. It’s always there. Anyway, since all of the other columns matched up, I assumed 2008 was okay, too. Delete the two summation rows (ours and theirs) as we don’t need redundant information anymore.

All this just to prepare the first data file for use, and we have two files to deal with. Think of all the time that WMATA could have saved us and everyone else trying to use these numbers if they had just given us their spreadsheet file. Had WMATA put in the few extra minutes ahead of time to give a link to their spreadsheet, it would have saved us half an hour (and multiply that by everyone else who did the same thing we did)! This is a great example of how data formats are not all equal. PDF is great for reading and printing, but it completely messes up tables. WMATA’s original file was probably a Microsoft Word or Excel file anyway — having either of those would have made our copy-paste job a breeze.

* * *

The second data file we’ll use has geographic coordinates of the transit stations. The final step of normalization involved some real manual labor to match stations in the historical data (our spreadsheet) to records in the GTFS data (in stops.txt). It was important to do this by hand because there were no consistent patterns in how stations were named across the two files. Some differences in names were:

|

Historical File

|

GTFS File

|

|

Gallery Place-Chinatown

|

Gallery Place Chinatown Metro

|

|

Station

|

|

Rhode Island Ave.

|

Rhode Island Metro Station

|

|

Brookland

|

Brookland-CUA Metro

|

|

McPherson Square

|

McPherson Sq Metro Station

|

|

Nat’l Airport (Regan)

|

National Airport Metro Station

|

It’s more than common for the naming of things to be different in different data sets. Here the differences included: punctuation (space versus hyphen), abbreviations (“Nat’l”, “SQ”), missing small words (“Ave.”), and added words (“METRO STATION”, “-CUA”). In fact, WMATA’s file misspells the name of the airport station! Trying to automate matching the names could get you fouled up: several dozen bus stops on Rhode Island Ave all look something like “NW RHODE ISLAND AV & NW 3RD ST,” and you wouldn’t want to pick up one of these to match against the Rhode Island Ave. rail stop mentioned in the historical data.

I looked through stops.txt for each of the 86 rows (transit stops) in the historical data and typed in the stop_id from stops.txt into a new column called gtfs_stop_id. This took about 20 minutes. (While I was there I also fixed some typos in the stop names that came from the PDF.)

Note that I didn’t copy-and-paste in the latitude and longitude, but instead copied the stop_id. I did this for two reasons. First, it would have been more work to type up two numbers per station instead of one. Second, copying over the ID leaves open the possibility of linking the two files together in other ways later on if new ideas come up. We’ll do the real combination in the next step. (WMATA could have included the GTFS stop_id in the ridership table as well. A few more minutes on their part would save the rest of us a lot of repeated effort.)

Build Something

The creative part of any open government application is the transformation. This is where you take the normalized data and make something new of it. Something new can be a website to browse the data, a novel visualization, a mobile app, a research report. For this example, I wanted to create two visualizations. The first will be a simple line chart showing the raw ridership numbers from year to year. That chart will show us time trends such as when stations opened, which stations are still growing in ridership, and which have leveled out. The second visualization will be a map of the change in ridership from 2009 to 2010. A map will let us see trends across Metro lines and neighborhoods.