Ancient Origins of Open Access to Law

It’s impossible to say exactly when and where open government data began, but a useful starting place is in open access to law. Three examples of open access and codification — in Archaic Greece, Visigothic Europe, and the American colonies — paint an interesting picture of how access to the law arose through anything but a democratic ideal.

Athens codifies its laws

When Athens codified its law in the 6th century BC, moving away from an oral tradition, it was a small part of a larger set of reforms implemented by the archon Solon. During this time, the public at large was of course not very literate. They could not have made much use of codified law. But according to author Jason Hawke, there is another reason to believe that the law was first written down not with the ideas of a participatory government in mind, but instead with the needs of the elites: The laws that were codified were those that kept wealth in place. Hawke wrote,

Plutarch states that Solon enacted a law forbidding dowries in all marriages save those which occurred between an heiress and her kinsman, the bride otherwise bringing with her only three changes of dress and inexpensive household goods. . . . These statutes regarding the control of property exhibit a common concern: the preservation and stability of the patterns of resource-ownership. . . . [T]he overall effect of such legislation was to conserve the distribution of wealth and resources and to prevent the easy movement of property and the de-stabilization of social and political arrangements within the community as a result.1

Athens was undergoing significant socio-economic changes during Solon’s time. Codification appears to have been a part of a reactionary program of holding onto a social structure upended by population growth and new wealth. Democratizing or equal justice ideals were not a reason for the modernization of law that took place.

Codification in colonial America

In colonial America, as in Archaic Greece, the codification of law emerged out of the needs of those in power. There, inexperience and a lack of information lead to gross economic confusion, and it was the need to end that confusion that lead to advances in government transparency. A Virginia critic wrote at the time that “the Body of their Laws is now become not only long and confus’d but it is a very hard Matter to know laws are in Force and what not.” As a result, “[t]owns were legislated into existence at inappropriate sites; . . . [and] the price of bread was assigned on sizes the bakers did not sell.” Codification arose out of frustration among legislators, as a means to attack other political offices, and perhaps also to rally their constituents.

The publicity probably began simply because legislators went home between sessions and found that their constituents had no copies of laws and no idea why the legislators were fighting the governors . . . [In 1710] the [Pennsylvania] assembly began publishing its acts and laws twice a week, partly so members could have up-to-date copies, partly so interested groups could appeal acts before the end of a session. Ten years after that, in 1720, the house began publishing its journals. In 1729 and 1740 it published codifications of its laws . . . Massachusetts began publishing its journals in 1715, again in a controversy with the governor, and put out a systematic compilation of the laws in 1742.2

While the effort to codify law may have not been aimed primarily to democratize access to the law, it was in retrospect a thankful consequence. Private citizens began making use of the text of the law in ways they could not before. According to Olson (1992), “Pennsylvanians annoyed with what they thought to be unfair practices on the part of flour inspectors in the 1760s confronted the inspectors with copies of the laws.”3 And by one account at least, 19th century codification was driven by a desire for greater certainty in and legitimacy of the law and for equal access to justice.4

Free access to law in Visigothic Europe

The law in 7th century AD Europe, under the Visigoths, provides the first instance of an open access law that I have found. At this point “data” was of course still 1,300 years into the future and even the printing press 900 years away. Written information in the 7th century was disseminated only at great pains through the scribe work of monks at a handful of monasteries.

The story of the first copyright law exemplifies the differences between then and today. When a monk copied the manuscript of a saint in 6th century Ireland, the reigning king decreed, “To every cow her calf, and consequently to every book its copy.” This decree ordered the monk to hand over his copy to the saint, and in so doing inventing the concept of copyright. But the more interesting event was the first appeal of a copyright ruling. The monk, unhappy with the decree, unleashed the military power of his family against the king, and he won.5 In these times when the loss of a single manuscript could be cause for an attack on the king, an open records law seems as though it would have made little sense, as the cost would have easily outweighed the benefit.

And yet, the promulgation of the law using price control was a part of public policy of the time. The Visigothic Code, written in Western Europe around 649-652 (but based on a legal tradition dating back well before that), set a maximum price that the Code itself could be sold for: “it shall not be legal for a vendor to sell a copy of this book for more than four hundred solidi,” or some $100,000–$400,000 today, the Code read. In setting a maximum price the Code seemed to intend to create wider access to the Code than would have otherwise occurred.

And yet a hint of its rationale can be found in another part of the Code. It also directed “bishops and priests to explain to the Jews within their jurisdiction, the decrees which we have heretofore promulgated concerning their perfidy, and also, to give them a copy of this book, which is ordinarily read to them publicly.”6 Given the enormous cost of creating a copy and low rates of literacy, I doubt this provision, the Code’s only provision for the free dissemination of the law, was carried out literally. But the law suggests that the purpose of the dissemination of the law was not to widen access to justice but instead to suppress dissidence. While this is the earliest open-records law that I’ve found, the legal tradition may have in any case ended when the Visigoths were replaced by the Moors less than a century later in 711.

The origins of government spending records in 17th century China

Open records practices can only occur if there can be an inexpensive but comprehensive infrastructure for information dissemination, and it was only 1,000 years later that we can start to trace a continuous history of open data. Modern open records laws probably drew more from 17th century China than any Western tradition of the time. Jean Baptiste du Halde wrote about the Chinese empire in the early 1700s:

Every three years they make a general review of all the Mandarins [officers] of the Empire, and examine the good or bad qualities that they have for government. Every superior Mandarin examines what has been the conduct of the inferior since the last informations have been given in, or since they have been in office, and he gives Notes to everyone containing praises or reprimands(\ldots)They reward a Mandarin by raising him to a higher degree, and they punish him by placing him in a lower, or by depriving him of his office.

The reviews would then be passed up the chain of command, each officer adding his notes onto those of his subordinates. At the highest level, where an account of all of the officers of the empire was put together, the punishments and rewards would be set and instructions would be distributed back down the chain of command, all the way down to the common people.

[T]he Mandarins are obliged to put at the head of their orders the number of degrees that they are to be raised or depressed: For instance: I, the Mandarin of this city raised three degrees, or depressed three degrees, do order and appoint, etcetera. By this means the people are instructed in the reward or punishment that the Mandarin deserved.7

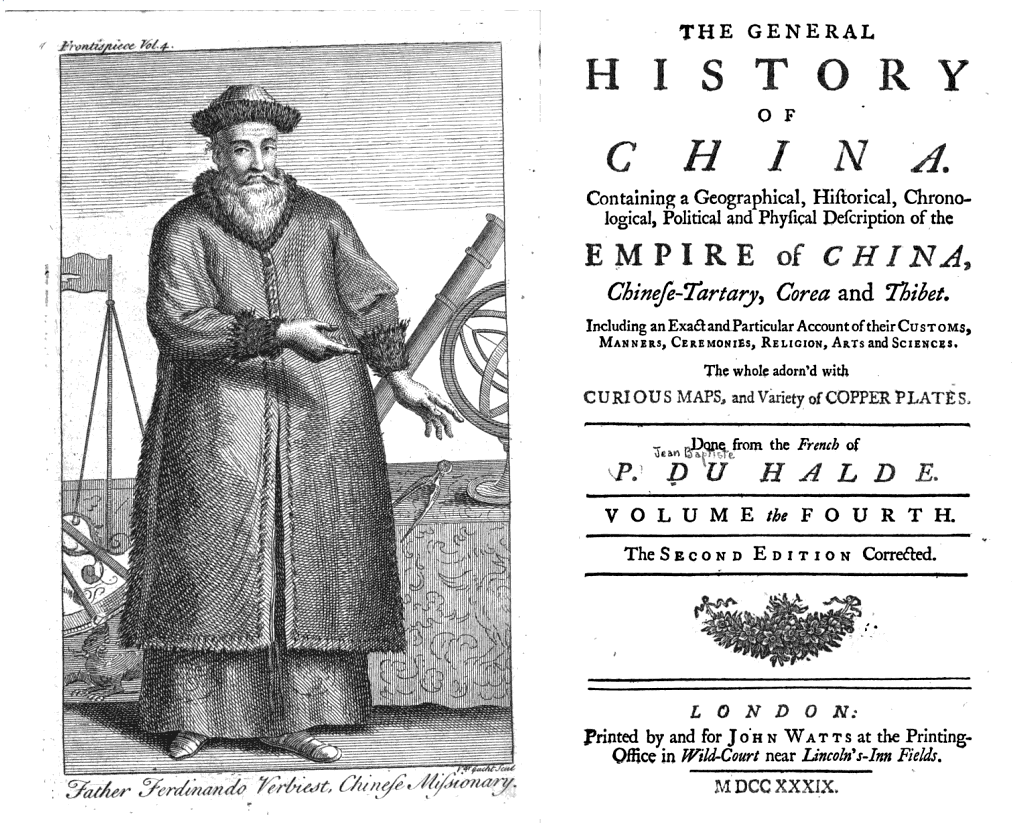

Figure 1. Front pages of Jean Baptiste du Halde’s 1736 The General History of China, which inspired the Western thinkers who created the first open records laws. (Scan from Google Books.)

Figure 1. Front pages of Jean Baptiste du Halde’s 1736 The General History of China, which inspired the Western thinkers who created the first open records laws. (Scan from Google Books.)

This first practice that du Halde was aware of was an interesting application of open records. Officers of the court were required to announce their own promotion or demotion in each of their orders.

The second remarkable practice that du Halde learned of was the Peking Gazette, published in the capital and distributed throughout the provinces of the empire. The gazette recorded punishments of officers, “expenses disbursed for the subsistence of the soldiers, the necessities of the people [probably care for the old and poor], the public works, and the benefactions of the prince,” and “laws and new customs that have been established.”8

Although the Peking Gazette appears to be a form of government disclosure and might have been seen that way by Western Enlightenment thinkers, its true purpose was surely for the emperor to “instruct the Mandarins how to govern,” as du Halde wrote.9 The gazette was most likely a form of government propaganda and control written in the form of an announcement.

The Freedom of Information in the Kingdom of Sweden

While the foundations of open records were present in the Visigothic Code, new practices in the American colonies, and the long tradition of the Peking Gazette, it was in the Kingdom of Sweden in 1766 that the wide dissemination of government records became a constitutional right.

Sweden was then a rare parliamentary government with a weak king, but it had not yet outgrown the common practice of the time of government-granted monopolies. Priest, farmer, doctor, and Enlightenment thinker Anders Chydenius, who would later promulgate offentlighetsprincipen, “the principle of publicity”10, had a problem with those monopolies. Chydenius’s home province in a remote part of the Kingdom had not received such a monopoly, and for the sake of free trade — or else for the sake of his own province’s well being — Chydenius demanded freedom of sailing at a local government meeting. His brief role in local politics was followed by a well-timed shift in political power which opened the door to his service in the national parliament in 1765–1766. There he continued to defend economic freedom and a new subject for him, the ability of the public to participate in the national debate.

Chydenius was inspired by the Chinese practices that he knew of through works by du Halde as well as the writing by one of his contemporaries, Anders Schönberg, who in the early 1760s called for the free publication of government documents, decisions, and voting records. But it was Chydenius as secretary of a committee on the freedom of the press that drafted what became the first known freedom of information act in history, combining both freedom of the press to publish as well as the right to access government information. These principles were enacted at the end of 1766 with much debate but no objection. Chydenius’s act guaranteed access to two types of government information, documents and records of votes:

[A]ll exchanges of correspondence, species facti, documents, protocols, judgments and awards . . . when requested, shall immediately be issued to anyone who applies for them.

[I]n order to prevent the several kinds of hazardous consequences that may follow from imprudent votes, likewise graciously decided that [judges] shall no longer be protected behind an anonymity that is no less injurious than unnecessary; for which reason when anyone, whether he is a party to the case or not, announces his wish to print older or more recent voting records in cases where votes have occurred, they shall, as soon as a judgment or verdict has been given in the matter, immediately be released for a fee, when for each votum the full name of each voting member should also be clearly set out . . . and that on pain of the loss of office for whosoever refuses to do so or to any degree obstructs it.11

Progress following 1766 had been relatively slow. In 1790, the French National Archive was founded and was open to the public three days a week.12

The Swedish law only remained in effect until King Gustav III’s coup six years later. Fifteen years later the United States Constitution was adopted without a general provision for access to government information. It did call for each house of Congress to maintain a journal.

Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such Parts as may in their Judgment require Secrecy; and the Yeas and Nays of the Members of either House on any question shall, at the Desire of one fifth of those Present, be entered on the Journal.

Today called the Congressional Record, Congress’s journal has been known to contain records of events that never occurred.13

The Swedish law returned in various forms elsewhere over the succeeding centuries. A Freedom of the Press Act is one of the four documents that comprise the current Swedish constitution. The second country to enact a FOIA law, after Sweden, was Finland, which had been a part of Sweden in 1766. Finland kept Chydenius’s spirit going through Russian control in the 19th Century and enacted its own law as a new country in 1919.14

-

Jason Hawke. 2011. Writing Authority: Elite Competition and Written Law in Early Greece. page 171–172. ↩

-

Alison G. Olson. 1992. Eighteenth-century colonial legislatures and their constituents. In The Journal of American History, 79(2), 543–567. ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

Norman W. Spaulding. 2004. The Luxury of the Law: The Codification Movement and the Right to Counsel. In Fordham Law Review, 73(3), 983–996. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4045&context=flr ↩

-

George Haven Putnam. 1896. Books and their Makers During the Middle Wages. Reprinted 1962, Hilary House Publishers. Page 46. ↩

-

Samuel Parsons Scott. 1910. The Visigothic Code: (Forum judicum). http://libro.uca.edu/vcode/visigoths.htm. Scott, the translator of the code, claimed 400 solidi was the equivalent of $17,600 in 1908, or approximately $400,000 today. As the solidi was 4.5 grams of gold, the same gold would have been worth just $110,000 in 1995 (the price of gold has fluctuated significantly since then). To give an idea for the length of the Code, it was translated and annotated within 500 pages. ↩

-

Jean Baptiste du Halde. 1736. The general history of China containing Geographical, Historical, Chronological, Political and Physical Description of the Empire of China, Chinese-Tartary, Corea, and Thibet. Second volume. John Watts: London. pp64–65. ↩

-

pp69–71. The gazette itself reportedly goes back 1,000 years, but this is the description of the earliest gazette I could find. ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

Juha Mannine. 2006. Anders Chydenius and the Origins of World’s First Freedom of Information Act, in The World’s First Freedom of Information Act: Anders Chydenius’ Legacy Today, ed. Juha Mustonen, Anders Chydenius Foundation. ↩

-

Peter Hogg. 2006. Translation from Swedish to English of His Majesty’s Gracious Ordinance Relating to Freedom of Writing and of the Press (1766) in The World’s First Freedom of Information Act: Anders Chydenius’ Legacy Today, ed. Juha Mustonen, Anders Chydenius Foundation ↩

-

Cynthia Warringa van Genderen. 2013. The Right to Know: A Comparative Legal Survey of Access to Official Information in Different Countries. ↩

-

The Open House Project Report, 2007. http://www.theopenhouseproject.com/the-open-house-project-report/10-the-congressional-record/ ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book