A Maturity Model for Prioritizing Open Government Data

The most common barrier to open government data is not that politicians or government employees oppose transparency but that open data programs compete with existing government programs for staff time. Cleaning data, preparing documentation, and finding cheap file hosting takes time — and therefore money. We live in a resource-constrained world where it is important to consider not just what we want, i.e. the principles of open government data, but also what we are willing to give up to get it.

Let’s assume a government agency is committed to an open government data program. Where should it begin? Should it build APIs for its largest datasets first? Or should it hire lawyers to remove data licenses?

The Invisible Hand

In their paper Government Data and the Invisible Hand, Robinson et al (2009) were the first, to my knowledge, to address the question of prioritization in the open government data movement. Their controversial suggestion — based in part on my success with GovTrack — was essentially to promote privatization of government services through open data. They wrote:

[T]o embrace the potential of Internet-enabled government transparency, [one] should follow a counter-intuitive but ultimately compelling strategy: reduce the federal role in presenting important government information to citizens. Today, government bodies consider their own websites to be a higher priority than technical infrastructures that open up their data for others to use. We argue that this understanding is a mistake. It would be preferable for government to understand providing reusable data, rather than providing websites, as the core of its online publishing responsibility.1

Robinson et al’s point was not that a government agency should not provide services over the Internet, only that the agency should first publish its data to encourage innovation in the private sector, which might develop services better than those the agency itself could. Often the private sector does anyway, and it would be more efficient for governments to promote it than develop in-house services.

Though this prioritization is controversial today, in fact many of the earliest open data government programs followed this approach. Most of us get our weather reports from sources other than the National Weather Service, but it is their data powering many of those forecasts. There is a cottage industry around data from corporate filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which abrogates the need for the SEC to provide comprehensive data browsing tools itself. And think of GPS signals: devices that receive GPS data are manufactured by the private sector.

Once the data is provided and the agency moves forward to providing services, the infrastructure that the agency created to publish data can and should be used by the agency to access its own public information. It is a common practice in technology companies to use your own software in order to make sure it works. Robinson et al continued:

Such a rule incentivizes government bodies to keep this infrastructure in good working order, and ensures that private parties will have no less an opportunity to use public data than the government itself does.

Robinson et al have, since publishing their paper, backed down from a literal reading of their suggestion. There are many reasons why it is infeasible for data to precede services. For one, government agencies are typically instructed by law to implement particular services, not to implement data. And certainly that’s for good reason. Public policy’s goal is to change the world, not describe it for the sake of data. But also, agencies who have hired staff to implement services may not have the skill set on hand to provide data instead, making a transition from services to data difficult.

Whether to do open data or service delivery is a matter of public policy that warrants discussion on a case-by-case basis. While there are data-first success stories, a blanket data-first policy is premature. But Robinson et al’s point is nonetheless instructive and raises the right questions about when it is appropriate to develop data.

A maturity model

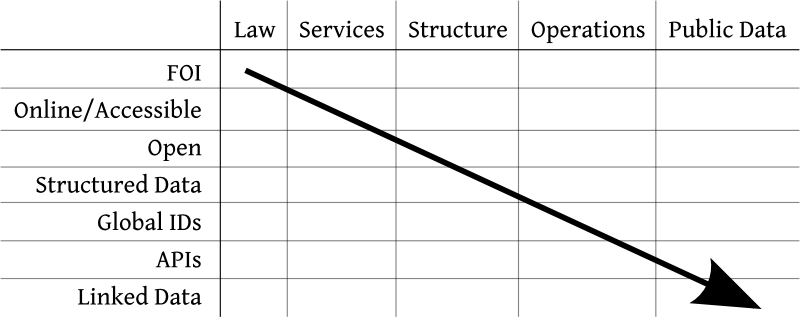

The chart in Figure 1 that I have developed provides a road map for deciding between the many aspects of open government data.

Figure 1. The open government data maturity model. Start at the top-left and go toward the bottom-right.

Figure 1. The open government data maturity model. Start at the top-left and go toward the bottom-right.

Down the rows on the left side of the chart are the different technological strategies of open government data: freedom of information, using the Internet, principles of openness, structured data, global IDs, APIs, and linked data (the semantic web). Across the columns at the top are the different sorts of public information governments produce: laws, service-related data, operational data such as rule-making dockets and spending records, and finally a catch-all column for other public data (sometimes produced incidentally to government functions).

The chart could be interpreted as a map of the open government data field — although that’s not the point I am trying to make. There are distinct communities in most of the 35 cells in the table above. Historically, starting around the 1950s, the open government movement was what we call today the right-to-know or the freedom-of-information movement. It was based on the idea, promoted by journalists, that there is a legal right to information held by the government. (For more on FOIA, see Legal History.) Modern government accountability focuses on the application of structured data to government operational processes (for my work, the legislative process), which is one cell toward the center of the table. There are distinct free access to law, government linked data, and spending data communities. Practitioners who work in one cell may have significantly distinct goals than those working in another cell, and a map of the landscape of open government data can help us navigate our community.

As a map, this chart expands on previous work by others in mapping the data and people in the open government data community. Yu and Robinson (2012)2 proposed a map with a horizontal axis from service delivery to public accountability and a vertical axis from inert data (think PDFs or audio records) to adaptable data (meaning structured data). Their horizontal axis appears in the columns above disguised as “Services” and, for accountability, “Operations”. But I have added to that axis new columns on either side. And I have, in a sense, divided their vertical axis into discrete technologies that range from inert (freedom of information) to adaptable (linked data).

But it is not my intention for the chart to be a map. Rather, the rows and the columns in this chart have an order. Some open government data projects should take precedence over others. Rows above should come before rows below. Columns to the left should come before columns to the right. (At least, roughly.) That makes this a maturity model in the sense that it outlines what proper growth looks like for government programs that implement open government data. Proper growth starts with freedom of information for laws and ends (if it ends) with public data on the semantic web. Don’t run before you can walk.

The vertical axis: Technologies

The rows of the maturity model are ordered according to their technological complexity. Each successive technology makes data more adaptable, in the sense of Yu and Robinson (2012). But the choice of technological complexity as the order is not based on desired outputs but instead on the fact that many of the rows cannot be accomplished without the previous rows having been completed first. That is, while the maturity model is intended to be normative, the ordering of the rows follows partially from logical necessity.

The order is also not from cheap to expensive. In fact, it may be just the opposite: technology helps us reduce costs in the long-term. For instance, the total cost of all FOIA-related activities across the federal government in FY 2008 was $338 million, mostly for the 3,691 full-time-equivalent staff processing FOIA requests.3 FOI, the first row in the maturity model, does not come cheap. In the maturity model, it is the starting point of no technology.

Freedom of Information

The legal right of FOI creates a presumption of openness, but, as you know if you’re familiar with FOIA in the United States, the right is not pro-active, it’s reactive. If there’s data you want, and you can figure out which agency has it, you can petition for that information. And if you’re lucky, the agency won’t object and claim one of the exemptions, if you’re lucky the agency won’t make you pay much to have the data retrieved and copied, and if you’re lucky you’ll get it in about a year. 50 years after FOIA was enacted, it’s pretty obvious we can do a lot better. The rows below this one build technology on top of the principle of freedom of information.

Online & Free

The first row after FOI is “Online & Free”. This principle says that while FOI provides a mechanism for making information public, information is not meaningfully public until it can be found on the Internet free of charge (except for the cost of Internet access). Uploading data and documents, in whatever form they already are in, is the first technological step in the maturity model.

Open

Eight core principles, plus six other principles, determine whether government data can be considered “open”. The “Open” row in the maturity model refers to six of the core principles of open government data: it is primary, timely, accessible, non-discriminatory, in non-proprietary formats, and license-free. (For a discussion on the meaning of these principles, see sections Online, Free, Primary, Timely, Accessible and No Discrimination and License-Free. This maturity model leaves machine processability for the next row.) This row, as with FOI, is primarily a matter of policy. In this case, technology policy like timeliness and license restrictions impact the usefulness of data — especially whether data can be used meaningfully to keep government accountable or affect policy change.

Structured

The next row is “Structured.” This is the first row that is purely technical, and it refers to creating data in such a way as to make it searchable, sortable, transformable, or, to put it generally, analyzable and machine-processable. Use spreadsheets instead of PDFs, use text instead of scanned images. Use XML. Break down fields into processable components. Applying structure to data requires an up-front technical investment but pays off by making the data more valuable. In this row, the open data that is published online is the original spreadsheet, an SQL database dump, or bulk XML data.

This is as far as most government agencies have made it on the technology of open government data. The remaining three rows guide future direction.

For more on the principle of analyzability and data formats, see Analyzable Data in Open Formats.

Global IDs

“Global IDs,” meaning globally unique identifiers, is the next row in the model. This is a type of structure that can be added to data. This concept is that any document, resource, data record, or entity mentioned in a database, or some might say every paragraph in a document, should have a unique identification that others can use to point to or cite it elsewhere.

There are many advantages of globally unique identifiers. Identifiers make information findable. For instance, a citation to a paragraph in the law (such as “22 U.S.C. 3301(b)(6)”) is a sort of identifier. The identifier uniquely pinpoints a paragraph in the United States Code.

When identifiers are shared across data silos, they create connections and make the data more adaptable. This is especially important for government spending data, where contract awardees might also be campaign contributors. A shared numeric identifier for each corporation facilitates a connection between these two typically separate databases. The value of the two connected datasets becomes more than just the sum of their parts. When identifiers persist across database versions, users of the database can process the changes from version to version more easily, making connections across time.

A web address (or URL) is a globally unique identifier. Any web address refers to that document and nothing else, and this reliability promotes the dissemination of the document as it provides a means to refer to and direct people to it. A commitment to use a particular web address is the basis for permanent links.

Modern globally unique identifiers are URLs that not only identify but also provide enough information to find information about the subject of the identifier on the Internet. For instance, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/22/3301#b-6 is a globally unique identifier to a paragraph in the U.S. Code. An easy (and accepted) way to choose a globally unique identifier is to piggy-back off of a web domain, which provides a “space” of identifiers that won’t clash with anyone else’s. For instance, you may coin http://www.youragency.gov/id/john_smith without any risk that someone in a different agency will use the same identifier to refer to something else.4

APIs

The combination of structured data and URIs is a read-only, web-based API, which is the next row in the maturity model. APIs are discussed in detail in the previous section.

There are technical, pragmatic, and principled reasons for why APIs cannot and should not come before bulk data. A web-based API cannot exist without structured data and a URL. An API is a mechanism for publishing the data that requires doing basically everything that bulk data does, plus much more. Pragmatically, agencies should validate the usefulness of bulk data before moving on to building APIs because APIs are more expensive to build. And, finally, APIs typically do not provide data in a manner consistent with the principles of open government data. See Bulk Data or an API? for details.5

Linked Open Data

The final row of the maturity model is “Linked Open Data” (LOD, see linkeddata.org), which is little more than a thorough application of structure, Global IDs, and APIs. Beyond this, linked data uses a particular data model called RDF and a particular API protocol called SPARQL. Linked data provides a high degree of interconnectedness across data silos in both the objects mentioned in the data (e.g. government contractors) but also in the concepts that relate the objects together (so-called predicates).

Promoted by the creator of the Word Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee,6 the Linked Open Data method for publishing databases achieves data openness in a standard format and the potential for interconnectivity with other databases without the expense of wide agreement on unified inter-agency or global data standards. Linked Data is a practical implementation of Semantic Web ideas, and several tools exist to expose legacy databases and spreadsheets in the LOD method. Though I have been writing about the uses of the Semantic Web for government data7 for as long as I’ve been publishing legislative data, it has not caught on in the United States, though it has become a core part of Data.gov.uk and is a recommendation of the Australian Governments Open Access and Licensing Framework8.

The W3C working draft Publishing Open Government Data9 and the Linked Data Cookbook published by the W3C Government Linked Data committee10 provide additional best practices with regard to globally unique identifiers and Linked Open Data.

As with structure, linked data requires careful work and an investment up-front, but it provides a basis, a unified framework, for answering complex questions that span data sources and even entire domains. This creates a level of adaptability far beyond what is possible in previous rows. But linked data is still an experimental technology.

The horizontal axis: Domains

The columns at the top of the maturity model cover the different sorts of public information governments produce. The columns are in a particular order from left to right. Whereas the order of the rows is based on a logical technological progression, the order of the columns is based on a set of normative values relating to the purpose of government. (Reasonable people may disagree on this order.)

The columns start on the left, where there is a moral imperative for the government data to be made available to the public, and end on the right, where access to public data creates additional benefit to society but for which there is no moral imperative to make the data available.

Law

The leftmost column is “Law”, and here the maturity model asserts that access to the law is the most important function of the many purposes open government data serves. A moral imperative to promulgate the law in all of the ways that increase access stems from respect for the rule of law and the principle that ignorance of the law is never a defense. The principle is quite a conundrum when the law is hard to find, difficult to understand, and, at times, illegal to share (see State Laws and the District of Columbia Code). Examples government data in the “Law” category are the text of the United States Code, judicial dockets, and information on potential laws (i.e. bills and regulatory proposals).

This moral imperative is only a starting point. Access to law has wider implications, as Carl Malamud writes on law.resource.org: improved civics and law education in schools, deeper research in universities, innovation in the legal information market, savings to the government, reduced costs of legal compliance for small business, and greater access to justice. Free public access to legal materials isn’t intended to necessarily replace the expensive subscription services for legal professionals, but instead to open up legal materials to a new audience.

Services

“Services” are next. Services are data produced in the furtherance of a government mission. Weather data is an example. The National Weather Service is, or at least was at one time, the largest producer of public data in the government. The Census was one of the first agencies to put data on the web. This sort of data is produced and distributed as part of the agencies’ core missions.

For service-related data there is no moral imperative to make the data available, but there is a legal imperative to further a public policy goal. If an agency’s mission is to produce information, publishing that information as open data can help it further its mission and achieve the goals that we, as a society, have prioritized for our government.

Operations

The next column is “Operations.” This sort of data is information about how government works, how it is being run, and how money is being spent. This is where government accountability looks for corruption, for instance, and it’s where we find out who represents us in government, who is making decisions, how representatives voted, and so on.

Only an educated public can hold its government accountable. This idea is rooted in the United States’s Bill of Rights, it is a common understanding of the role of journalism in society, and, even if that were not all true, it is a moral underpinning of democratic government.

Public Data

Last is the catch-all column “Public Data.” This is, for instance, some sorts of Medicare and Medicaid claim statistics. Or geographic data about the location of every single road in the country. This is data for which there is no moral imperative to make public, at least not the sort of moral imperative that exists for law data, and there is no legal imperative to pro-actively make it available either. In a resource-limited world, this sort of data is not a high priority for open data. But making the data open, structured, and so on produces value to society. It is civic capital. Entrepreneurs can build businesses around this data. (Think Google Maps and its predecessors, built originally off of government data and government GPS signals.)

-

David G. Robinson, Harlan Yu, William P. Zeller, and Edward W. Felten. 2009. Government data and the invisible hand. Yale Journal of Law & Technology, 11. p160. ↩

-

Harlan Yu and David G. Robinson. February 28, 2012. The New Ambiguity of “Open Government.” ↩

-

http://www.justice.gov/oip/foiapost/2009foiapost16.htm ↩

-

URLs are a type of “dereferencable” identifier because they can take you from reference to referent, i.e. to a document describing what the identifier identifies. ↩

-

The Australian Governments Open Access and Licensing Framework makes an API a core part of data access, placing its recommendation under the heading “open query” and before “open bulk supply,” which I believe is a poor strategy. http://www.ausgoal.gov.au/ausgoal-qualities-of-open-data, accessed July 10, 2011. ↩

-

Tim Berners-Lee. June 24, 2009. Putting Government Data Online. ↩

-

See Building a Civic Semantic Web, an article I wrote for Nodalities in August 2009. ↩

-

http://www.ausgoal.gov.au/ausgoal-qualities-of-open-data, accessed July 10, 2011. ↩

-

Daniel Bennett and Adam Harvey. September 8, 2009. Publishing Open Government Data (W3C Working Draft). ↩

-

Bernadette Hyland, Boris Villazón Terrazas and Sarven Capadisli. 2011. Linked Data Cookbook. ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book