Democratizing Legal Information

Not everything is about corruption. Many open government projects, including one of my own, are about creating access to primary legal documents. Two factors distinguish projects that democratize legal information from the sort discussed previously that aim to be a “disinfectant.” First, the projects in this section do not presume that anything in particular is wrong with government. No judgment is made. Second, the value of these projects to their users is more direct than the value of the projects discussed in the previous section — an idea I’ll return to later.

The legal materials that have received focus by U.S. projects include congressional bills (e.g. by my own GovTrack.us and WashingtonWatch.com by Jim Harper), state legislation (Richmond Sunlight by Waldo Jaquith, Knowledge As Power by Sarah Schacht, and the Open States Project of the Sunlight Foundation), administrative law (Federal Register 2.0), statutory law (Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute and Virginia Decoded by Waldo Jaquith), and case law (RECAP out of Princeton University, all among many others). What these projects all have in common is digging deeply into a particular aspect of law, generally making the text available in a way it was not before, and often providing additional tools to track changes to the law.

Carl Malamud has been leading an effort to fill in the gaps where primary legal materials are not (freely) available to the public at all. Some of the gaps are state codes. Much of the gaps are judicial decisions and related court documents which make their way behind pay-walls run by private companies (Westlaw, LexisNexis), associations (the American Bar Association), and the courts themselves. Malamud, I don’t think, would fault private companies for selling value they add to public documents, but he does criticize the courts and academia for not living up to a higher standard:

Our law schools and our law libraries are not active in maintaining the corpus of primary legal materials. We’ve outsourced this important function, and as a consequence, America is not being well served . . . Today, law libraries risk becoming a 7-11, where one vendor comes in and fills up the donut case, another stocks the ATM, and your job is all about managing vendors and answering an occasional query from a customer.1

Malamud’s project, under the moniker Law.Gov (but the website is law.resource.org), points to many practical implications of broad access to the law: improved civic education in schools, deeper research in universities, innovation in the legal information market, savings to the government, reducing the cost for small business of maintaining legal compliance, and greater access to justice. Free public access to legal materials isn’t intended to necessarily replace the expensive subscription services for legal professionals, but instead to open up the legal materials to a new audience.

All of the benefits to the public in the last paragraph of access to the law are what I meant by the value of these projects being more direct. A website that aims to reform government has indirect value to the public. First the public has to use the information to elect better policymakers, then the policymakers hopefully make better policy, and decades later the public benefits from the new policy. In the case of Law.Gov, the benefit is direct and immediate. Reduced costs for small business is reduced costs now.

The most useful place to read the U.S. Code has been on the website of the Cornell University Legal Information Institute (LII), at http://www.law.cornell.edu, which since 1992 has run the most effective browse and search interface for the Code and other primary legal documents. One of LII’s innovations has been creating permalinks to particular paragraphs within the legal documents. Although the Government Printing Office began publishing the Federal Register and Code of Federal Regulations in XML in 2009, and the House of Representatives’ Law Revision Counsel publishes the United States Code in XML, errors in the application of the XML formats of those documents have slowed the LII’s progress in making use of those files to create a more richly functioning website2 (though they have been used to create the Federal Register applications discussed in Introduction).

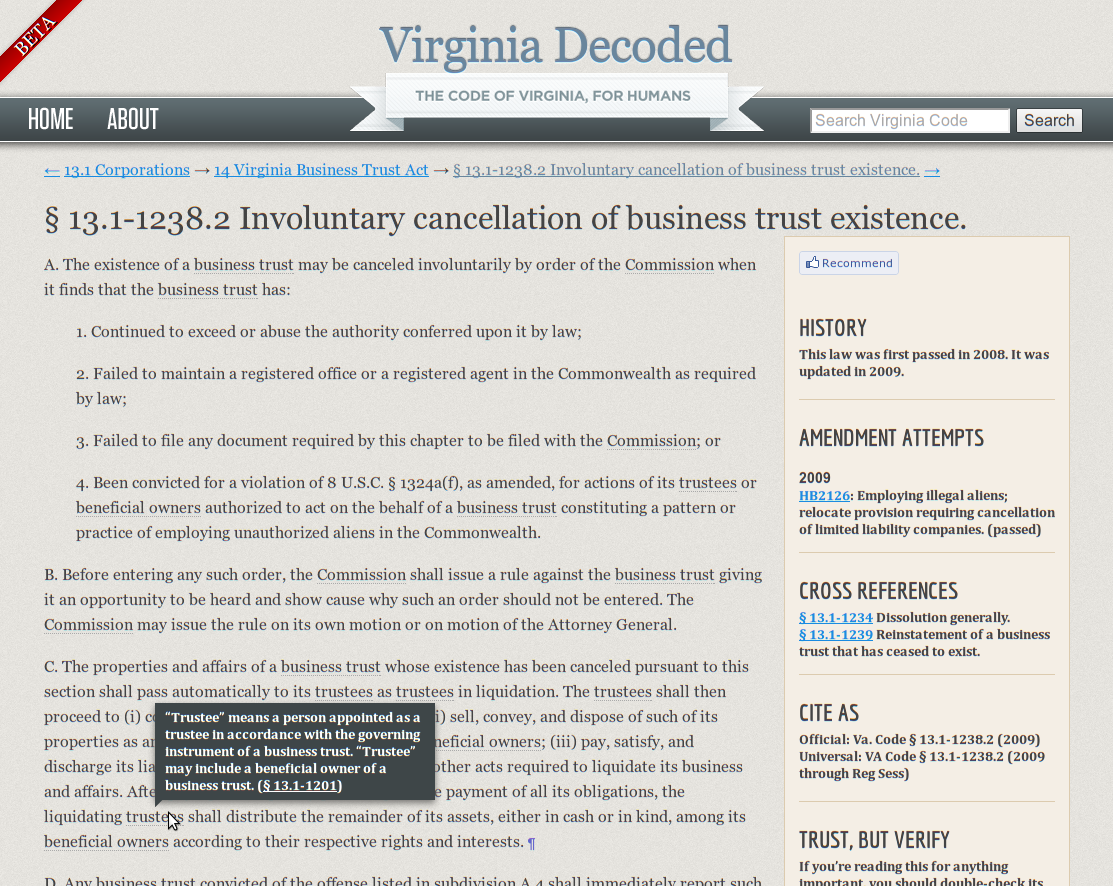

Figure 1. Virginia Decoded (vacode.org) is the first state launched in Waldo Jaquith’s State Decoded project. The website shows the state’s laws with tools including pop-up definitions of terms from other parts of the code, suggested citation text, history, cross references, and a link to the corresponding page of Virginia’s official website for each part of the code.

Figure 1. Virginia Decoded (vacode.org) is the first state launched in Waldo Jaquith’s State Decoded project. The website shows the state’s laws with tools including pop-up definitions of terms from other parts of the code, suggested citation text, history, cross references, and a link to the corresponding page of Virginia’s official website for each part of the code.

A lot can be done with technology to make the law more accessible. Waldo Jaquith described the goal as “display[ing] local laws and court decisions in a way that provides clarity and context” using “embedded definitions, cross-referencing links, helpful explanations, commenting, tagging, decent design, and humane typography.”3 Virginia Decoded (vacode.org) was the first state Jaquith launched in his State Decoded project. Figure 1 shows the site’s pop-up definitions of terms, which are sourced from other parts of the code, suggested citation text, and other tools that help the reader to read and make use of the law. (Jaquith previously created RichmondSunlight, which is a legislative tracking tool for the Virginia state legislature, similar to GovTrack.) There are now State Decoded sites for eight states including the District of Columbia. The future of democratized law might be flow charts and other visualizations.4

In State Laws and the District of Columbia Code I discuss the opening of the District of Columbia Code and questions about who owns the law.

-

Carl Malamud. 2011. Twelve Tables of American Law. ↩

-

For some background see LII founder Thomas Bruce’s testimony to the House Committee on House Administration, June 16, 2011. ↩

-

Jaquith’s proposal for his State Decoded project, a 2011 Knight Foundation grantee, at http://vimeo.com/25083822 ↩

-

Helena Haapio and Stefania Passera. May 15, 2013. Visual Law: What lawyers need to learn from information designers. VoxPopuLII. ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book