History of the Movement

Looking at its history, the open government movement has come out of three very distinct communities, says Justin Grimes: open government advocates whose focus had typically been on the Freedom of Information Act (see Ancient Origins of Open Access to Law for the history) and money in politics, open source software and open scholarly data advocates, and open innovation entrepreneurs (who might include both Gov 2.0 entrepreneurs and government staff looking to the public for expertise, such as in Peer-to-Patent, see Consumer Products). To each group, “open” means something different. Other distinct communities that preceded the modern movement included participatory budgeting and free access to law. Open government draws on all of these aspects of “open” and from each of these communities. (For more see 20 Basics of Open Government and Harlan Yu’s dissertation1.)

But open government data is distinct from open government. Although the most interesting applications of open government data can be found within the open government movement, open government data has its own history rooted in Web 2.0, political campaigns, and innovations inside of municipal governments.

Government goes online

Federal government

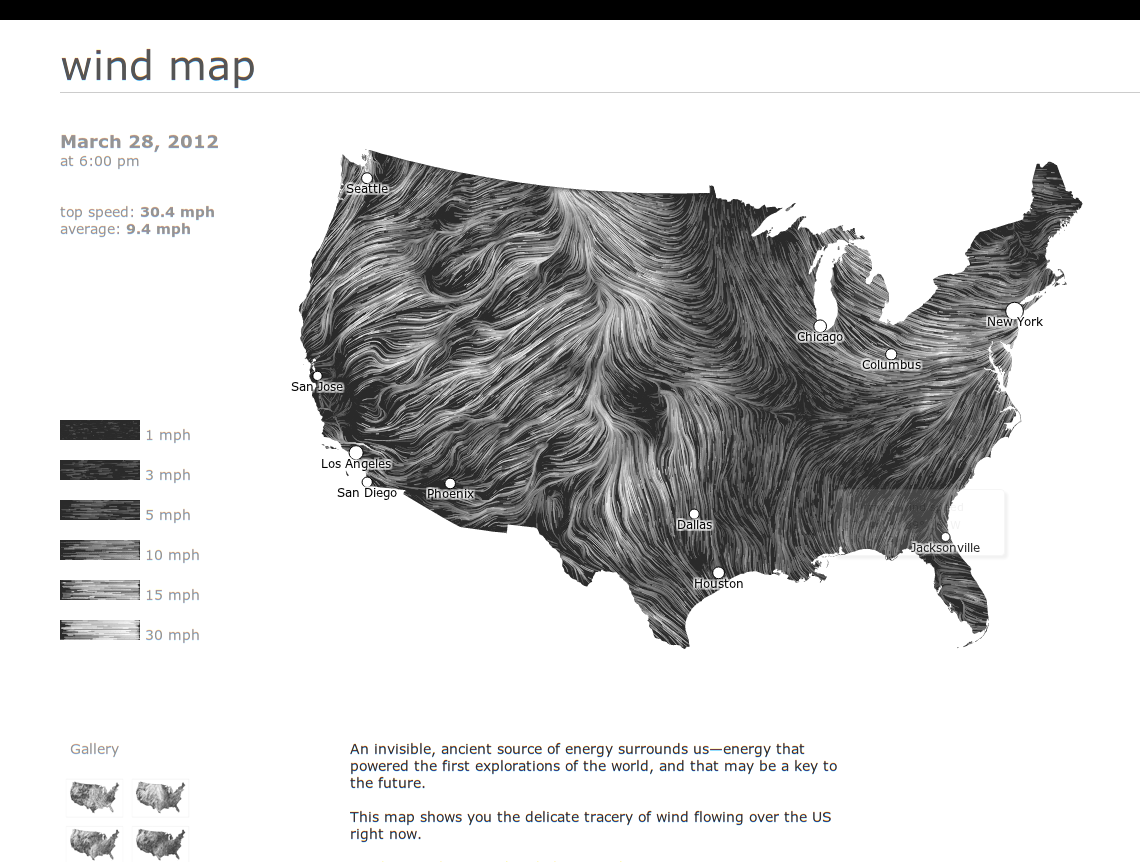

For as long as there has been the modern weather report there has been business around government-produced information. The National Weather Service has long published its raw data on the Internet — how long I’m not sure — and its director of strategic planning and policy Edward Johnson told me in 2009, “We make an enormous amount of data available on a real time immediate basis that flows out into the U.S. economy.” Both their free-of-charge data and specialized high-reliability and high-bandwidth services are a crucial foundation for daily weather programming and weather warnings in newspapers and on television. (For a new use of weather data, see Figure 1.)

Figure 1. This animated visualization of live wind speeds and directions uses data from the National Weather Service’s National Digital Forecast Database. The animation was made by Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg, the pair behind IBM ManyEyes, and can be found at hint.fm/wind.

Figure 1. This animated visualization of live wind speeds and directions uses data from the National Weather Service’s National Digital Forecast Database. The animation was made by Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg, the pair behind IBM ManyEyes, and can be found at hint.fm/wind.

Weather reports predate the Internet, of course, but when government went online massive amounts of new data became available. The Government Printing Office (GPO), which is the publisher of many of the government’s legal publications, went online in 1994 with the Congressional Record (one of Congress’s official journals), the text of bills before Congress, and the United States Code.2 The Republican Party, which was in the minority at the time, published its Contract with America that year with an emphasis on public accountability. Though the Contract did not mention the Internet, when the Republicans took control of the House the following year they created the website THOMAS.gov in January 1995, the first website to provide comprehensive information to the public about pending legislation before Congress. Later that year the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted a system originally created in the private sector to disseminate corporate filings to the public for free (more on that later). In early 1996 the Federal Election Commission (FEC) opened fec.gov, which was not only a website but also a repository of the raw data the FEC compiled. That data could then be analyzed independently by researchers and journalists.3 That year the Census Bureau made the Internet its “primary means of data dissemination.”4

Partisan politics may have driven some of this innovation, as in the case of THOMAS.gov, but information access was not confined to the Republican party. The 1994 Circular A-1305, a memorandum from the Clinton Administration to executive branch agencies, might have been the earliest official policy statement asserting the public’s right to know through information technology. Still, high level policies like those expressed in Circular A-130 haven’t typically trickled down through federal agencies without some external pressure on the agency.

The opening up of the SEC’s database was one of those cases where external pressure was crucial. Since 1993, EDGAR has been a database of disclosure documents that various sorts of corporations are required to submit to the SEC on a regular basis. The disclosure documents have been intended to ensure investors and traders have the information they need to make informed decisions — making for a fluid trading market. However, in 1993 this “Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval System” was not available directly to traders. It was run under contract by a private sector company which in turn charged “$15 for each S.E.C. document, plus a connection charge of $39 an hour and a printing charge of about $1 a page.”6 But to Carl Malamud and others including Rep. Edward Markey, the price kept the information from many more traders who could not afford to access the information supposedly needed to make informed trades. (For comparison, at that time access to the Internet for an individual cost around $2 per hour.)

In a carefully executed series of moves Malamud was able to successfully incentivize the SEC to publish EDGAR to the public directly. With help from a grant from the National Science Foundation, contributions from other technologists, and New York University, Malamud bought access to the full EDGAR database and began making it available to the public, over the Internet with search capabilities, for free.7 Then after nearly two years of running the service and distributing 3.1 million documents to the public, Malamud fulfilled his stated plan to shut it down — but not without some fanfare. A New York Times article contrasted the SEC’s legal obligations with a stubbornly dry press statement:

The [Paperwork Reduction Act] says agencies with public records stored electronically have to provide “timely and equitable access” in an “efficient, effective and economical manner.”

“The law is real clear they’ve got to do it,” Mr. Malamud said.

But a spokesman for the commission, John Heine, said it was “too early to tell” whether it would take over Internet distribution of the Edgar documents. Mr. Malamud is asking “some of the same questions we’ve been asking ourselves,” Mr. Heine said.

. . .

“We’ve done two years of public service, thank you,” Mr. Malamud said, adding that he had personally financed a portion of the project.8

Four days later the SEC changed its position9 and worked with Malamud to adopt his service as their official method of public distribution over the Internet. Malamud’s technique was effective, and he has repeated the technique since: buy and publish government data, change public expectations, and then shame government into policy change.

As the federal government went online, entrepreneurs in the private sector began transforming and republishing the information. Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute, established in 1992, expanded its website’s collection of primary legal documents over the next two decades to support research and make the law more accessible. The Center for Responsive Politics’s website OpenSecrets.org launched after the 1996 elections. OpenSecrets takes campaign contribution records published by the Federal Election Commission then significantly cleans up the data, analyzes it, and publishes it in a form that is accessible to journalists and the public at large to track money’s influence on elections. These are the longest running open government technology projects.

In the first ten years of the government going online, information technology was seen only as a tool for fast and inexpensive information dissemination. Data liberation, as it is called, is only the first part of open government data. What GPO began putting online in 1994 were the same documents it had been printing since 1861. That was absolutely the right place to start, and those documents are still crucial. Legal and scholarly citations today are largely by page and line number, so it is important to have electronic forms of printed documents that are true to the original’s linear, paginated form. But open government data can be so much more.

Municipal government

Entrepreneurship in government transparency was beginning in municipal and state governments around the same time as well. Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley was facing one of the highest crime rates in the country, high taxes, and an under-performing government. He created CitiStat in 1999, an internal process of using metrics to create accountability within his government. The city’s information technology staff became a central part of the accountability system, and by 2003 CityStat’s information technology infrastructure was used to create a public facing website of city operational statistics.10 The CitiStat program and website were replicated in other state and local governments: DCStat in 200511, Maryland’s StateStat launched in 2007 when O’Malley became governor, and New York City’s NYCStat launched in 200812. StateStat in Maryland has been credited with policy outcomes including reducing childhood hunger and cutting costs.13

Although CitiStat, DCStat, StateStat, and NYCStat focused on performance reports and metrics rather than providing raw underlying data to the public, they proved through practice that data was valuable to keeping governments productive and accountable. Now data analysis is becoming common in city governments. Predictive analytics has helped Chicago’s Department of Public Health better allocate its 32 restaurant safety inspectors, at least in a recent preliminary study.14 Boston’s Office of New Urban Mechanics modernized the city’s “311” service hot-line.15

Putting a spin on the performance dashboards that evolved from CitiStat, Washington, D.C.’s chief technology officer Vivek Kundra created the D.C. Data Catalog at data.dc.gov in 2007, the purpose of which was to spur innovation by providing the public with raw data held by the D.C. government.16 (Although the D.C. Data Catalog is regarded as the first open data catalog, and it may have been the first to see itself as a part of a bigger picture of openness and innovation, it was not the first data catalog. There were earlier data catalogs, but mostly for the exchange of geospatial data, such as Pennsylvania’s PASADA spatial data portal which began in the late 1990s.) Less well known, Louisville, Kentucky passed a financial transparency bill in 2009 that put salaries, budgets, revenue, and audits on a website that eventually became the city’s data catalog.17

Modern open government

The call to action for technologists in the private sector came less from open government advocates or new government programs but rather from the infusion of “Web 2.0” and “mashups” in the grassroots digital campaigning of the 2004 presidential elections.

This was especially so in the Howard Dean presidential campaign. Independent developers supporting the Dean campaign specialized the open source content management system Drupal for political campaigns, making CivicSpace (now CiviCRM). The campaign’s novel uses of the Internet and the CivicSpace project in particular were widely publicized. That sent a message that developers have a role to play in the world of civics. It perhaps began the notion of civic hacking.

By the next election bloggers were playing a serious role as part of the news media, and new yearly conferences including the Personal Democracy Forum began giving political technology legitimacy.

Michael Schudson, a professor in the Columbia Journalism School, wrote,

It is not only that the techies see themselves as part of a movement; it is that they see the technology they love as essentially and almost by nature democratic (but in this I think they are mistaken).18

It’s certainly true that we techies see technology as having a unique role to play in governance.

Separately but around the same time as the rise of the Internet in politics, GPS navigation devices were starting to become popular. GPS is one of the earliest and yet most successful examples of government-as-a-platform, a concept recently promoted by Tim O’Reilly (the founder of O’Reilly Media). GPS is a signal sent by U.S. government satellites. Until the year 2000, the federal government intentionally degraded GPS signals for civilian use. Once that policy ended, GPS quickly became ubiquitous.

GPS signals are often combined with data from the Census Bureau on the nation’s roads and the U.S. Geological Survey’s satellite imagery and terrain data to create maps. Maps and public transportation have been a popular subject for developers.19 Early applications in the modern open data movement were crime maps based on local police data. Adrian Holovaty’s chicagocrime.com website in 2005 was one of the first Google Maps mashups, and its successor, Holovaty’s EveryBlock website, helped jump-start the open-data movement:

In 2007, we were basically the first consumer-focused entity with a full-time person (Dan O’Neil) devoted to convincing city governments to open their data feeds. At the time, city employees responded to us as if we were crazy. “You want WHAT? A daily feed of every crime? How about I give you these paper printouts once a month?” We did a ton of informal lobbying, spoke at relevant conferences and (most importantly) built a product based on civic data that showed municipalities that there was consumer-level demand for their stuff.

. . . Since we changed focus to neighborhood discussion in March 2011, EveryBlock users have used our service to accomplish amazing things in their neighborhoods: starting farmers markets, catching flashers, raising money for their community, finding/reporting lost pets . . .20

EveryBlock was initially funded by a grant from the Knight Foundation’s News Challenge contest and was later acquired by MSNBC.com. Foundations and corporations alike have created sustainability for civic hacking projects.

The crystallization of “civic hacking” continued with the formation of the Sunlight Foundation, a DC-based nonprofit whose goal has been to use technology to increase government transparency and accountability. The foundation was started by its first executive director Ellen Miller who had run the Center for Responsive Politics (mentioned above as one of the longest running open government data projects), funder Mike Klein (a lawyer and entrepreneur who discovered the value of commercial real estate data), and advisor Micah Sifry who had started the Personal Democracy Forum. Sunlight’s lead technologist several years later, Clay Johnson, got his start in political technology by working as the lead programmer for the Howard Dean presidential campaign.

The foundation’s first major project, The Open House Project, brought together open government experts, existing nonprofits pursuing accountability, and new civic hackers (including myself) for the first time. The project issued a report to the U.S. House of Representatives on the use of technology to improve transparency. (For more on the Open House Project and Sunlight Foundation’s hacking projects, see Sunlight as a Disinfectant.)

Following the Open House Project in 2007, Carl Malamud — who had liberated the SEC data in the ’90s — lead a workshop that wrote the “8 Principles of Open Government Data.” The 8 Principles gave us consensus on general principles that guide how governments should release data to the public, including that the data should be timely, in a machine processable format, and not restricted by license agreements (for the full principles see Principles).

The idea of machine processability is that information technology can make it easier to search, sort, share, discuss, and understand government publications — not just read them — if the data is made available in a raw, normalized format. There isn’t much a computer can do with a scanned image of a book. It can’t read the words. But computers can help us when we have good data, such as a spreadsheet, or a more modern data format such as XML.

Open government data began to truly take off in 2009. This was the year of the first two Transparency Camp conferences run by the Sunlight Foundation, numerous apps developed outside of government, and a new interest in open government from inside of government.

In the legislative branch, the Senate began publishing the results of roll call votes in XML format (the House had been doing this for six years already), and the House began publishing its spending data electronically (more on that in Data Quality).

The Government Printing Office recognized that legal documents could be useful in other electronic forms besides electronic renditions of paper (i.e. a PDF). So along side its publication in plain-text and PDF of the Code of Federal Regulations and the Federal Register, cornerstones of the federal regulatory law, GPO added bulk-data downloads in XML format, which makes it possible for innovators in the private sector to create new tools around the same information.21 The Archivist of the United States explained what happened next:

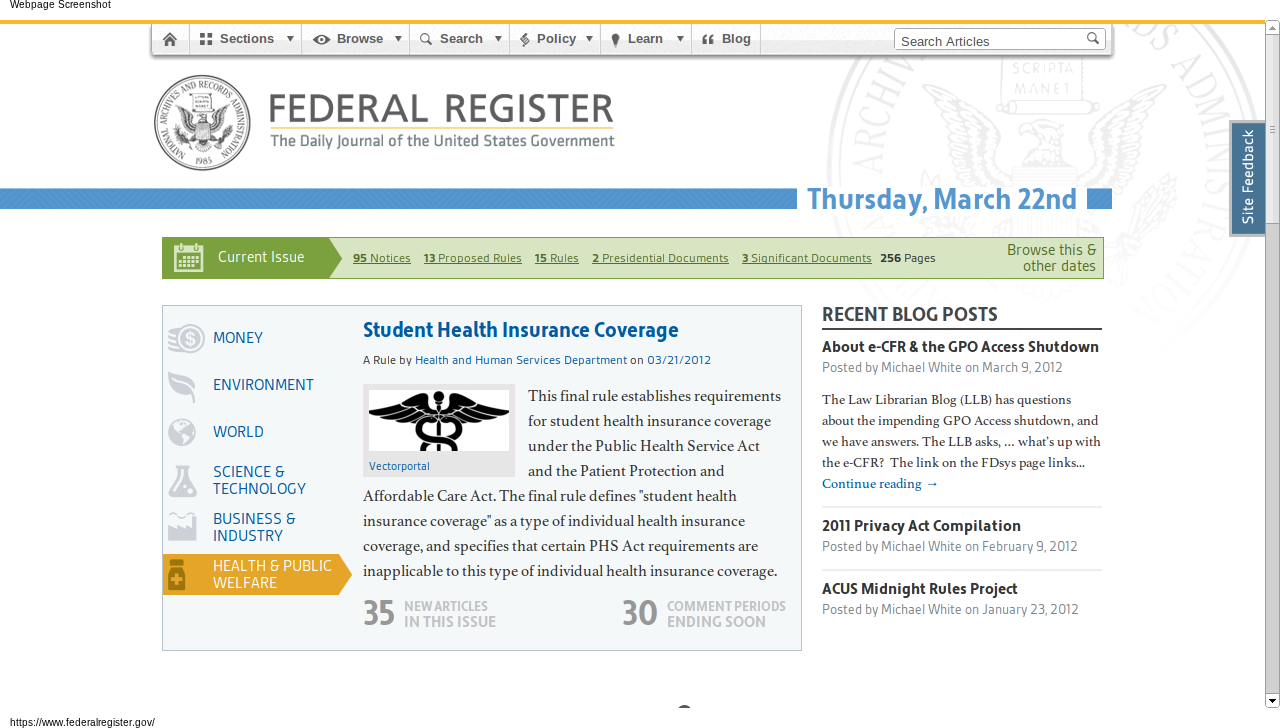

In August 2009, Andrew Carpenter, Bob Burbach, and Dave Augustine banded together outside of their work at WestEd Interactive in San Francisco to enter the [Sunlight Labs Apps for America 2] contest using data available on data.gov. Understanding the wealth of important information published every day in the Federal Register, they used the raw data to develop GovPulse.us, which won second place in the contest. In March 2010, the Office of the Federal Register approached the trio to repurpose, refine, and expand on the GovPulse.us application to bring the Federal Register to a wider audience. Federal Register 2.0 is the product of this innovative partnership and was developed using the principles of open government.22

GovPulse.us, a private sector innovation using open government data, became the new official Federal Register 2.0 at federalregister.gov, shown in Figure 2. The new site makes the Federal Register publication vastly more accessible to anyone who is not an experienced government relations professional through search, categorized browsing by topic and federal agency, improved readability, and clear information about related public comment periods. GovPulse wasn’t the only project to create an innovative tool based on the Federal Register XML release, though it has been the most successful. FedThread, created at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy, was a collaborative annotation tool. (It was discontinued in 2011.) And FederalRegisterWatch.com by Brett Killins provides customized email updates as search queries match new entries published in the Register.23

Figure 2. The new Federal Register 2.0 at federalregister.gov makes the Federal Register publication vastly more accessible to anyone who is not an experienced government relations professional. It was created as a submission to a contest and later adopted by Office of the Federal Register as the official site.

Figure 2. The new Federal Register 2.0 at federalregister.gov makes the Federal Register publication vastly more accessible to anyone who is not an experienced government relations professional. It was created as a submission to a contest and later adopted by Office of the Federal Register as the official site.

What happened with EDGAR and the Federal Register is happening with all of the most important government databases (both in the United States and abroad): actors in the private sector are stepping up to empower the public through not merely online access to government publications — we’ve had that since the ’90s — but through a digital transformation of government data into completely new tools.

The movement was also spurred by policy changes in 2009.

President Obama’s Open Government Directive (December 8, 2009) re-framed the world-wide movement. This was so, in part, because it presented a definition of “open government” which many found appealing:

The three principles of transparency, participation, and collaboration form the cornerstone of an open government.

While transparency was a core component of open government from the beginning of the open government movement in the 1950s, participation and collaboration were relatively new and certainly untested.

Each of those three parts of the definition of open government was to be backed up by a new White House technology project. Data.gov, a dataset catalog, and an information technology spending dashboard were launched early that year as new efforts to promote transparency.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) stood out as one of the few federal departments that hadn’t had a prior commitment to open data that has strongly embraced the Directive, now having released to the public data sets including FDA drug labeling and recalls, Medicare and Medicaid aggregate statistics, national health care spending estimates, and most recently an API reporting adverse drug events (reported side-effects). HHS has been actively promoting reuse of their data with an Apps Expo, contests, and code-a-thons.24 (U.S. federal open data policy is discussed in greater detail in U.S. Federal Open Data Policy.)

But even as the White House’s interest in transparency was soon replaced by an interest in using open data to spur economic activity, Data.gov spurred a world-wide movement of data.gov-style catalogs in cities and countries throughout the world25, some of them better than our own here. Data.gov.uk, for one, has innovated in the application of Semantic Web technology to establish connections between datasets from different agencies. The Open Government Partnership, launched in 2011, is a multi-government effort to advance parallel transparency reforms in participating countries, focusing on disclosure, citizen participation, integrity, and technology.26

At the municipal level, strong open data or civic hacking initiatives have been under way in San Francisco, Chicago27, Boston28, and New York City29. Cities have been creating new Chief Data Officer roles spearheading open data and sometimes city analytics, starting with Chicago (in 2011)30, Philadelphia (in 2012)31, San Francisco (in 2012)32, Baltimore (in 2013)33, the District of Columbia (in 2014)34, and Los Angeles (in 2014)35. For a living list of U.S. open data policies, see Sunlight Foundation’s list of current and emerging policies at the state and local level.

-

Harlan Yu. 2012. Designing Software to Shape Open Government Policy. Doctoral dissertation, Princeton University. Page 114–117 (open government), 120–122. ↩

-

FEC 1996 Annual Report http://www.fec.gov/info/arfrm.htm ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau: Publishing Results. Accessed March 28, 2012. ↩

-

The circular itself was available via Telnet and FTP on the Internet, according to its own notes. ↩

-

John Markoff. October 22, 1993. Plan Opens More Data To Public. The New York Times. ↩

-

The New York Times. August 12, 1995. An Internet Access to S.E.C. Filings to End Oct. 1. ↩

-

The New York Times. August 16, 1995. S.E.C. Seeks to Keep Free Internet Service. ↩

-

Lenneal J. Henderson. May 2003. The Baltimore CitiStat Program: Performance and Accountability. IBM Endowment for the Business of Government. ↩

-

http://dcstat.octo.dc.gov/dcstat/lib/dcstat/Document.pdf, http://www.nascio.org/awards/nominations/2006WashingtonDC3.pdf ↩

-

Mayor’s Office of Operations, New York City. An introduction to New York City’s NYCStat Reporting Portal. Accessed March 28, 2012. ↩

-

Beth Blauer. 2013. Why Data Must Drive Decisions in Government, in Beyond Transparency, http://beyondtransparency.org. ↩

-

David Raths. 2014. What Do Public Health Officials Want From Big Data? Government Technology. ↩

-

Sam Roudman. August 9, 2013. New Study Looks Under Hood of Boston’s New Urban Mechanics. Tech President. ↩

-

Memorandum from the Office of the city Administrator to all agency heads and directors, Government of the District of Columbia. 2006. http://www.scribd.com/fullscreen/26442622 ↩

-

Theresa Reno-Weber and Beth Niblock. 2013. Beyond Transparency: Louisville’s Strategic Use of Data to Drive Continuous Improvement, in Beyond Transparency, http://beyondtransparency.org. ↩

-

Michael Schudson. 2010. Political observatories, databases & news in the emerging ecology of public information. Dædalus. (The parenthetical is his.) ↩

-

For more see http://www.citygoround.org/, http://www.opendataphilly.org/opendata/resource/162/septa-bus-and-trolley-location-api/, and http://policybythenumbers.blogspot.com/2012/01/transit-transparency-open-data-in.html. ↩

-

Adrian Holovaty. August 15, 2012. Onto the next chapter. ↩

-

Ed O’Keefe. October 5, 2009. Federal Register Makes Itself More Web-Friendly. The Washington Post. ↩

-

David Ferriero. July 26, 2010. Coming Soon: Federal Register 2.0. National Archives Blog. ↩

-

In both the cases of the EDGAR database and Federal Register 2.0, the government adopted a private sector project as an official government service. USASpending.gov was also created in this manner, starting as a project of the nonprofit OMBWatch (now the Center for Effective Government), called FedSpending.org, which was a searchable database of federal contracts. It was later bought by the Office of Management and Budget and became USASpending.gov as part of the implementation of the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (S. 2590, 109th Congress), sponsored by Sen. Tom Coburn and Sen. Barack Obama. However, these public-private collaborations are otherwise quite rare. ↩

-

http://www.health2apps.com/category/applications. In 2012, long after writing this paragraph but before anyone had seen it, HHS hired me to help build HealthData.gov which launched June 5 of that year. ↩

-

The history of open government data is substantially different in the United Kingdom. For more on that, see Halonen, Antti. 2012. Being Open About Data: Analysis of the UK open data policies and applicability of open data. Additionally, an excellent timeline of events influential in the open government data movement in the United Kingdom can be found in Davies, Tim. 2010. Open data, democracy and public sector reform. http://practicalparticipation.co.uk/odi/report/. ↩

-

Alex Howard. August 17, 2011. Opening government, the Chicago way. O’Reilly Radar. ↩

-

Sam Roudman. August 9, 2013. New Study Looks Under Hood of Boston’s New Urban Mechanics. Tech President. ↩

-

Alex Howard. October 7, 2011. How data and open government are transforming NYC. O’Reilly Radar. ↩

-

Brett Goldstein. 2013. Open Data in Chicago: Game On, in Beyond Transparency; Kelly Ng. August 14, 2014. City of Chicago Chief Data Officer Tom Schenk - A Bigger Role Than Others, Asia Pacific FutureGov. ↩

-

Matt Williams. August 8, 2012. Philadelphia Gets a Chief Data Officer ↩

-

Noelle Knell. October 15, 2012. San Francisco to Hire Chief Data Officer, Government Technology. ↩

-

Colin Wood. June 5, 2013. Baltimore Fills New Chief Data Officer Role, Government Technology. ↩

-

Mayor Garcetti Appoints Abhi Nemani as City’s First Chief Data Officer ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book