State Laws and the District of Columbia Code

In late 2012, DC-based civic hacker Tom MacWright wanted to build a website for the Code of the District of Columbia, the legal code that is the compilation of the statutes enacted by the DC Council. Intending to import the DC Code into Waldo Jaquith’s State Decoded project, a general platform for creating modern websites for state codes, MacWright ran into a small problem: he couldn’t get a complete copy of the law. Intellectual property issues prevented him from making a copy of the law from electronic sources and prevented the DC Council from simply emailing over their copy of the Code.

What is law?

It was very disconcerting the first time I came to grips with the fact that the law is so hard to find. There are both theoretical and practical reasons for this. On the theoretical side, federal statutory law works in such a way that for most of the law there is no actual document produced which you could say is actually the definitive law. The law comes about piecemeal through actions of government. The law is the culmination of those actions, regardless of whether the culmination itself is written anywhere. For instance, let’s say a bill called the Puppies Are Cute Act reads, “Puppies are cute.” The bill is enacted. Then a second bill amends the law by reading, “Strike the first word of the previous law and insert in its place ‘Cats.’ ” Nowhere is the current law “Cats are cute” actually written, but that is the law. In a sense, statutory law is the hypothetical document that would result if you tried to put all of the enacted bills together.

The United States Code is that compilation of the statutes, but it is not (at least in part1), the actual law. A similar situation exists for administrative law, which is the law created by executive-branch agencies through power delegated by the legislative branch. U.S. administrative law is created through publication of rules changes in the Federal Register. The compilation of those rules forms the Code of Federal Regulations.

Case law is not open

The judicial branch has no such compilation. Case law can only be determined by reading and interpreting court-issued opinions. But while bills, the Statutes at Large, the Federal Register, the United States Code, and the Code of Federal Regulations have been available for free and online for a long time now, court opinions and the documents in the dockets surrounding those opinions are held in a tightly-guarded electronic system called PACER run by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. Harlan Yu described PACER’s pay-wall:

But the biggest problem with PACER by far is its pay-for-access model. The Courts charge PACER users a fee of ten cents per page to access its records. This means that, when looking for a case, searches will cost ten cents for every 4320 bytes of results — one “page” of information according to PACER’s policy. Once the case is found, obtaining a docket that lists all of its documents could — for lengthy cases — cost another dollar or two. To download a specific document in the case, say a 20-page PDF brief, the user would be charged another $2.00. While each individual charge may seem small, the cost incurred by using PACER for any substantial purpose racks up very quickly.

Even at many of our nation’s top law schools, access to the primary legal documents in PACER is limited for fear that their libraries’ PACER bills will spiral out of control. Academics who want to study large quantities of court documents are effectively shut out. Also affected are journalists, nonprofit groups, pro se litigants, and other interested citizens, whose limited budgets make paying for PACER access an unfair burden. Even the Department of Justice paid $4 million in fees in 2009 to access these public records.2

Pay for access makes a joke out of PACER’s full name, Public Access to Court Electronic Records.

Since these documents are generally not subject to copyright or other legal restrictions on redistribution, giving access to the public is legal if only the documents could be obtained. After Aaron Swartz downloaded 19,856,160 pages from PACER through a free trial (saving himself $1.5 million), all free trials were quickly suspended.3 RECAP, a project out of the Princeton University Center for Information Technology Policy at recapthelaw.org, attempts to create a public repository of court documents by asking lawyers to contribute PACER documents they paid to access into the RECAP public repository. RECAP is a web-browser extension that automates the process of uploading PACER documents to RECAP, and it works not so much because of a technological breakthrough in uploading so much as in human interface design: creating a method that is easy for lawyers to use. (RECAP is PACER spelled backwards.)4

Read the law on an iPad, go to jail

Many states, like the District of Columbia, contract out the codification and code-publishing work to the major legal publishers like West (owned by the Canadian-owned Thomson Reuters) and Lexis (owned by the Amsterdam-based Reed Elsevier). This creates unfortunate incentives for not only the publishers, but also the states who rely on the publishers, to keep the law behind a pay-wall.

In 2008, the State of Oregon claimed that its laws were copyrighted and threatened the website Justia and Carl Malamud5 for publishing Oregon’s laws for the public to read for free. As Ed Walters, the CEO of Fastcase explained, the problem extends far beyond Oregon:

LexisNexis believes that it owns the Georgia Code. And the statutes of Colorado, Wyoming, and Mississippi. The free Websites of many state legislatures contain copyright notices warning the world that copying public law is illegal and punishable under copyright law.6

In May 2013, Carl Malamud bought the Official Code of Georgia Annotated, scanned them, and put them online to improve public access. The Georgia Code Revision Commission, which is the government body that publishes the code, replied, “CEASE AND DESIST ALL COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT” (yes in capital letters).

The Georgia commission’s claim is that while the law itself is not copyrighted, it is inextricably intertwined in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated with other explanatory material called annotations which don’t have the force of law, and thus are copyrightable. An average citizen who wants to read the law — because he is responsible for knowing all of it — does so at his own risk in Georgia. The Official Code of Georgia Annotated doesn’t delineate what parts are the actual law, what parts are copyrighted by the commission, and what parts are copyrighted by the publisher LexisNexis. Although a legal expert can guess that what they’re referring to is the part printed in a smaller font size, an average citizen might face a costly lawsuit for copy and pasting a page of the law into a blog.

States have used two tactics to get around the limitations of copyright law: statutory fines and superfluous contracts. In Delaware, making a copy of Title 8 of the Delaware Code can result in a $500 fine and 3-month imprisonment per 8 Del. C. 1953, § 397. In other words, they created a mini-copyright for themselves for just one title of the law.

Citizens who use Georgia’s official website7 for reading its laws must assent to a contract before doing so. Here is one term:

You are hereby granted … the rights to use the Research Service on one single-user personal computer.

[Y]ou may not, nor may you permit others to … copy all or any portion of the Research Service8

You hereby represent and warrant that all use of the Research Service will comply with this Agreement and all federal, state and local laws, statutes, rules and regulations.9

Does that mean you can’t read the law on a device you share with your family members, like an iPad? And surely you don’t plan to break any laws by reading the law, but what if you do? Not only do we not withhold the law from those convicted of crimes, we actually provide the law to prisoners to assist in their own defense. The contract, even though innocuous sounding, is antithetical to public access.

Terms of use create civil penalties, if not also criminal penalties such as jail time. Online, the distinction between civil and criminal is wiped away by the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, under which violations of website terms of service agreements like these can lead to federal felony charges.10

(Ed Walters of Fast Case has written extensively about who owns the law. For a video, see http://reinventlawchannel.com/ed-walters-who-owns-the-law/.)

Freeing the DC Code

In the case here in DC, two things stopped MacWright. First, DC had contracted out to West the publishing of their code. DC’s official website to read the DC Code at that time was free to the public, in a sense, but copying any part of the Code off of that website would have violated West’s copyright or terms of service, or both. Sharing the law might have been illegal!

Second, the DC Council had Word documents containing the Code, given to them by their contractor West, but the documents contained West’s logo. The DC Council could not share the documents with West’s logo intact. And it wasn’t easy to take those logos out. Informally speaking, West owned the DC Code.

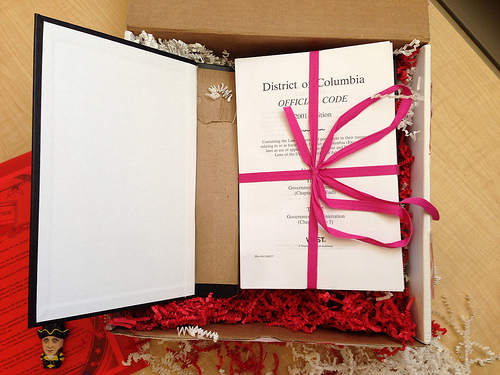

MacWright asked Carl Malamud to get involved. Malamud had opened the Securities and Exchange Commission’s corporate filings database in the 1990’s (discussed in Introduction), and he had more recently been working on the issue of opening state codes in other states (discussed in Democratizing Legal Information).11 Malamud gave an encore to the technique he began in the 1990’s when he opened the SEC data (he bought the data, put it online, pressured the government to put the data online themselves, and then helped the government take over that responsibility). Malamud bought a physical copy of the DC Code, digitized it, and mailed physical copies and USB thumb drives (in the shape of famous Presidents) containing the digitized code to people who would blog about it. (See Figure 1.)

He also mailed a copy to the DC Council’s general counsel, V. David Zvenyach, the tech-savvy lawyer responsible for publishing DC’s statutory laws. Zvenyach had already been trying to modernize the office he took over only a few years prior (he and I had even talked about holding a hackathon to help him do that long before there was interest in the DC Code). But his office, like all of government, was bound by limited resources and much work to do. When MacWright brought the issue onto Zvenyach’s radar, Zvenyach didn’t see why MacWright’s request deserved priority over other things his office has to do.

Figure 1. Carl Malamud distributed physical and electronic copies of the DC Code. This shipment went to Waldo Jaquith. The George Washington-shaped USB thumb drive (right) contained the digitized version from Malamud’s scans of the physical edition. (Photos courtesy of Waldo Jaquith.)

Figure 1. Carl Malamud distributed physical and electronic copies of the DC Code. This shipment went to Waldo Jaquith. The George Washington-shaped USB thumb drive (right) contained the digitized version from Malamud’s scans of the physical edition. (Photos courtesy of Waldo Jaquith.)

The media and bloggers caught on to the free law issue. An article in The Washington Times on March 31, 2013 wrote about the conflict between “ignorance of the law is no excuse” and that “WestLaw [has] a monopoly on the D.C. Code.”12 The local blog DCist13 and others also covered the issue.

Some of the articles focused on how the DC Council claimed a copyright over the Code,14 a fact Malamud had noticed early on. It seemed, at first, as though the DC Council intended to restrict access to the law. Such copyrights may not even be valid.15 But as Zvenyach explained in The Washington Times article, the rationale was to protect DC from West, by making sure West could not claim copyright over the same Code, not to limit public access to the law.

Zvenyach wasn’t immediately convinced, but my offer to do the work of stripping West’s logo from thousands of places in those Word documents was an offer he saw no reason to refuse. So I sat in his office for an afternoon and wrote some Microsoft Word macros to do it. We also took out DC’s copyright notice from the documents. And on April 4, 2013 DC’s legal code went online on the DC Council’s website as open data. The Creative Commons CC0 public domain dedication was used to release copyright claims over the files, to boot. Never had I worked with a government body that moved so deftly through the technical, policy, and legal issues as Zvenyach’s office did. (Zvenyach is today a civic hacker in his own right.)

DC set an example for other jurisdictions. In terms of Malamud’s 10 Principles of Law.Gov16, DC’s bulk law download — achieved within only a few days of work — satisfies principles of no-charge to access, no copyright or terms of use, data in bulk, and, to some extent, it was analyzable.

Zvenyach is now working to publish DC’s laws in a structured data format and under the stricter guidelines of Uniform Electronic Access to Legal Materials Act (UELMA), a bill proposed in many state legislatures, including DC. UELMA requires that official, electronic legal materials have public access, be preserved, and be digitally signed (for more, see Permanence, Trust, and Provenance). (I have been a consultant to Zvenyach’s office on this project.)

-

Parts of the U.S. Code, called the positive law titles, are themselves the law. The original statutes compiled in those titles have been repealed and the titles themselves have been enacted into law. ↩

-

Harlan Yu. 2012. Designing Software to Shape Open Government Policy. Doctoral dissertation, Princeton University. ↩

-

John Schwartz. February 12, 2009. An Effort to Upgrade a Court Archive System to Free and Easy. The New York Times. ↩

-

For more see https://www.recapthelaw.org/why-it-matters/. ↩

-

Ed Walters. 2011. Tear Down This (Pay)wall: The End Of Private Copyright In Public Statutes. In VoxPopulii. http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2011/07/15/tear-down-this-paywall/ ↩

-

http://www.legis.ga.gov/, which is run by LexisNexis ↩

-

accessed April 3, 2014 ↩

-

For more details, see my blog post at http://razor.occams.info/blog/2014/04/03/reading-the-law-on-an-ipad-in-georgia-you-could-go-to-jail/. ↩

-

Zoe Lofgren and Ron Wyden. 2013. Introducing Aaron’s Law, a Desperately Needed Reform of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. In Wired; Kim Zetter. June 29, 2016. Researchers Sue the Government Over Computer Hacking Law. In Wired. ↩

-

Luke Rosiak. March 31, 2013. Ignorance of D.C.’s copyrighted laws can be costly. The Washington Times. ↩

-

Martin Austermuhle. March 28, 2013. Breaking the Law to Publish the Law: Open Government Advocate Digitizes Entirety of D.C. Code. DCist. ↩

-

Their registered copyright can be found by searching cocatalog.loc.gov for “District of Columbia code.” ↩

-

Tim Armstrong. 2008. Can States Copyright Their Statutes?. ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book