Consumer Products

Open government has traditionally been about access to information. When you think about open government applications, the first to come to mind are those that expose otherwise hard to find government information. That was the case in both the disinfectant category of apps whose primary users are journalists and watchdogs and in the legal materials category of apps whose primary users are wonks and professionals. But there is a new category of consumer-focused open government applications. These applications aim to serve needs everyday people actually have while simultaneously facilitating better governance. It is a sort of government-as-a-platform approach to civic problems.

mySociety

Tom Steinberg, who leads the U.K. nonprofit mySociety, summarized the idea behind this category best:

People have needs. Sometimes they need to eat, sometimes they need to sleep. And sometimes they need to send an urgent message to a local politician, or get a dangerous hanging branch cleared off of a road. What people never, ever do is wake up thinking, “Today I need to do something civic,” or, “Today I will explore some interesting data via an attractive visualisation.”1

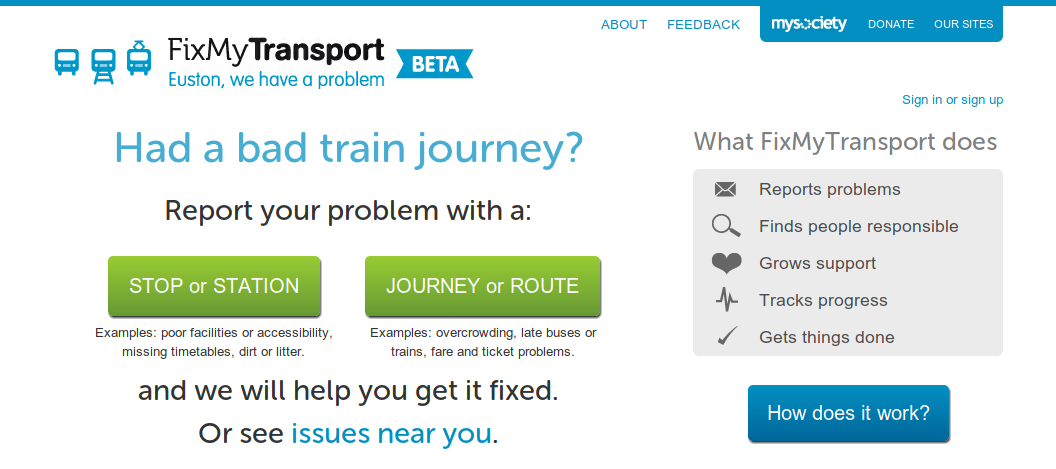

FixMyTransport by mySociety lets U.K. public transportation riders report problems, such as litter, late buses, or ticket problems. And other visitors to the site can give you advice about the problem you are having. The application improves governance by helping the government address these issues faster and better. It does so without accusing the government of doing a bad job, and probably gets better results because of that. It is a consumer product because people want to vent when they have a problem, and this site lets people do that (in a constructive way).

Figure 1. FixMyTransport by mySociety lets U.K. public transportation riders report problems, such as litter, late buses, or ticket problems, to public transit officials.

Figure 1. FixMyTransport by mySociety lets U.K. public transportation riders report problems, such as litter, late buses, or ticket problems, to public transit officials.

SeeClickFix and Open311 are similar projects in the United States.

Peer-to-Patent

Many personal motivations can be guided into improving governance. Above, the motivation to vent about a problem was guided into improving public transit. Another successful example of this is the Peer-to-Patent program created by Beth Simone Noveck:

Like every government official faced with the task of making important decisions with too little time and access to too little information, patent examiners have only between 18-20 hours to read, research and write up the determination of which applications deserve to become a patent . . .

With the consent of the inventor and the USPTO, the Peer-to-Patent project posts a pending application online for three months during which time the volunteer public can read the application, discuss it with others, submit suggested avenues for research, submit prior art, and rate the submissions of others for relevance to the pending application.2

Peer-to-Patent is not really a consumer product. Its goal is to improve the patent process, and it has no apparently direct benefit for the expert volunteers that participate. So why do people participate? According to Noveck, a drive to perform public service is one factor. But there are other factors:

Yet others want to show off their expertise in the hope that they will get noticed and hired by the inventor, the USPTO or other participants. They participate in order to add it to their resume.3

Who would have thought that such self-interest could actually improve governance, right?

POPVOX

The problems addressed by disinfectant-oriented projects and consumer-oriented products can be similar. mySociety’s WriteToThem.com and POPVOX, a company I co-founded in 20104, help people contact their Members of Parliament or Members of Congress. Like traditional open government applications, these two websites also have something to do with government accountability. But the approaches are different from websites that indict government as broken and not listening.

At POPVOX, we found that constituent letters to Congress are often lost in an overloaded system. Congressional offices received more than 200 million emails in 20045, and extrapolated to today it is around 300 to 2,000 emails each day for each congressional office. Congressional offices only have a small staff to process the incoming letters. They tally the letters, select a limited few to share with the Member of Congress, and write bulk replies to constituents who wrote in on the same issue. Congressional staff readily admit that they don’t have the capacity to read each letter thoroughly. That’s unfortunate because Americans put in a lot of time writing these letters, trying to make convincing arguments, and advocacy organizations pay a substantial amount of money to P.R. firms and Internet services companies to get their supporters to write in to Congress.

This is a problem of scale. Everyone has an opinion, but there is no way for a single congressman to process 710,000 ideas (the approximate average population of each of Congress’s 541 congressional districts) or for a single senator to process 37 million ideas (the population of California). Before email, the cost to the constituent to share his or her opinion was high. That acted as a natural filter, and there was a time, long ago, when mail volume was so low — because it was costly — that Members of Congress read their own mail. Today no such filter exists, and it would be a shame to impose an artificial cost to telling your Members of Congress what is important to you.

How do you solve this? In planning our road map at POPVOX we considered personas, caricatures of the different sorts of individuals that we had something to offer. We talked about Cynical Cindy who wants to keep Congress accountable, Aspirational Aaron who wants to run for office, and Issue Isabel who has a deep, personal connection to an issue and will put in the time to rally her cause. And because some of the most successful products tap into the deepest parts of our humanity, we even looked for what might be the embarrassing motivations that drive each persona, whether it be pride, greed, or the need to feel connected. Putting users first is the core of the “lean startup” philosophy. One of our advisors told us that a company’s value proposition is the intersection of the company’s goals with its users’ desires and needs. Successful products tap into those desires and needs.

POPVOX has been successful because it addresses a governance problem by being a consumer product. Like Peer-to-Patent, it crowd-sources expertise that helps government make good decisions by tapping into the personal motivations and interests of its users. And also we were smart about how we delivered letters, making sure that they were in a format most useful to the congressional staff handling them.

In our first year of operation POPVOX delivered hundreds of thousands of letters to Congress, many containing personal stories of how public policy affects real lives. Letters were on issues as diverse as health care, gun carrying rights, military pay, and the slaughter of horses. The letters were constructive and contained a wealth of information that may have influenced policy-making. And I was especially proud that even in this time of such low approval of Congress, the vast majority of letters written were actually in support of a bill, rather than in opposition. There are still ideas in Congress that the public can rally around.

-

Tom Steinberg. August 30, 2011. How to create sustainable open data projects with purpose, in O’Reilly Radar. ↩

-

Beth Simone Noveck. 2011. Peer to Policy. Draft For Yale-Oslo Conference On Epistemic Democracy in Practice, October 2011. ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

. . . and left in 2012. ↩

-

Congressional Management Foundation. 2005. Communicating with Congress: How Capitol Hill is Coping with the Surge in Citizen Advocacy. ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book