Data Quality: Precision, Accuracy, and Cost

Many of the principles of open government data relate to a notion of data quality, meaning the suitability of the data for a particular purpose. Timeliness, for instance, is important if the data is to be useful for decisions in ongoing policy debates, but what constitutes “timely” depends on the particular circumstances of the debate.

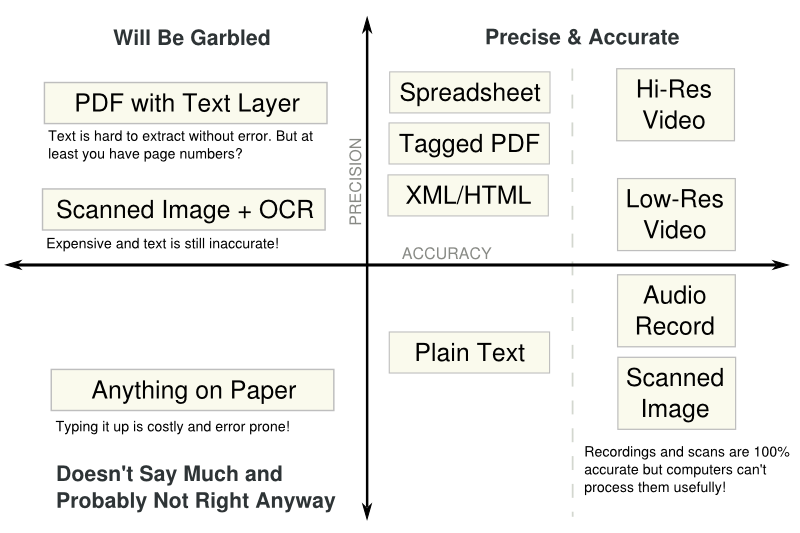

The choice of data format similarly depends on the purpose. For financial disclosure records, a spreadsheet listing the numbers is more useful for making use of those records than an image scan of the paper records because the intended use — searching for aberrations — is facilitated by computer processing of the names and numbers not by knowing the position of the numbers on a page. If the most important use of the records were instead to locate forged signatures, then the image scans would become important. Data quality cannot be evaluated without a purpose in mind — and an expectation of reasonable cost.

Government data normally represents facts about the real world (who voted on what, environmental conditions, financial holdings) and in those cases two measures become important: precision and accuracy. Precision is the depth of knowledge encoded by the data. Precision comes in many forms such as the resolution of images, audio, and video and the degree of dis-aggregation of statistics. Accuracy is the likelihood that the data reflect the truth. A scanned image of a government record is 100% accurate in some sense. But analog recordings like images, audio, and video have low precision with regard to the facts of what was recorded (more on that in a moment).

Accuracy

Governments have long prioritized accuracy in information preservation and dissemination. In an analog world, we protect legal artifacts from physical degradation and malicious alteration because the value of the artifact is in its form. The same principles have been carried over to digital records. When a document is scanned into an image for archiving, we should be concerned that pixel-for-pixel the scan reflects the physical document it was produced from.

But when judging the accuracy of digital records about something, the notion described above is limiting. When the scanned image lists facts — names, numbers, or other information — then the pixels themselves matter little. Instead what matters is whether we can discern those facts. Here we should be concerned that someone reading the scanned image gets the correct understanding of what is in the image. Think of a noisy audio recording. The recording may correctly reflect the sounds that were actually present at the time of the recording, but people listening to the recording might still not understand — or misunderstand — what was said. In that sense, the recording might have low accuracy.

And in a computer-assisted world, we should be concerned about whether our tools can correctly “understand” the data. Optical character recognition software turns scanned images into text, but the process is usually not very accurate. I’s turn into 1’s and L’s, 5’s become 8’s, and so on. The ramifications of these character swaps may be enormous. Imagine trying to compute the sum of all government spending using a table in which any digit might be swapped with any other — it would be impossible.

Humans are not as susceptible to these issues as OCR software. We can read noisy images better than computers can, but we can’t do it as fast . . . or as cheaply. And so accuracy comes at a cost. With cheap computers we can turn tens of thousands of pages into text, and from there compute sums and other statistics, but at low accuracy because of the swapped 5’s and 8’s. Or at great expense we could employ people to do the same thing. When government records are born digital there is no need for OCR. And yet governments often print and re-scan documents, turning them into images. This is often done in the name of accuracy — in the sense of preventing documents from being altered. But in fact it decreases accuracy because it has increased the cost for anyone to get a correct understanding of what a document says, which is the goal.

Precision

Precision is the depth of knowledge encoded in data. A summary report has low precision, while a detailed spreadsheet has high precision. Data with high precision can be used by specialists such as developers, designers, and statisticians to write articles that explain the data, to create infographics, or to transform the same information into other consumable forms.

In a structured data format (a spreadsheet or XML), greater precision breaks fields down into more subcomponents. For instance, this might be the difference between a single field for a name versus breaking the field down into first, middle, and last name components. This can be important when we want to use the name. Names are particularly difficult to process in an automated way because they are idiosyncratic. For instance, Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Shultz is “Rep. Wasserman Schultz” not “Rep. Shultz” as you might think. Her last name defies convention by having a space separate the two parts rather than a hyphen. And so in a spreadsheet of names of Members of Congress, a single name field containing “Debbie Wasserman Shultz” would almost certainly lead to an embarrassing outcome of causing someone who does not know the idiosyncrasy to refer to the congresswoman by the wrong name. Splitting her name into components — “Debbie”, no middle name, and “Wasserman Schultz” — would avert the problem. Encoding a name like this is more precise.

As with accuracy, precision comes at a cost. Given the less precise spreadsheet that has a single column of names, it is still possible to determine each Member of Congress’s last name (“Wasserman Schultz” and not “Schultz”) with 100% accuracy. However, to do so might require hiring an intern to call up each individual Member of Congress and ask what exactly his or her last name is. Then one can know with certainty the right way to refer to the congresswoman. Precision would be high, but only at a high cost. (If the intern calls only half of the Members of Congress and guesses last names for the rest, the precision remains high but accuracy would be reduced! That is, there is some chance the intern’s guess is wrong.)

Why accuracy and precision have been at odds

Precision is often at odds with wide public consumability. A prepared report, which is still data, may be easily consumable by a general audience precisely because it looks at aggregates, summarizes trends, and focuses on conclusions. In these cases, we care that the report is legible so that when read (by people, not OCR’d by machine) it has high accuracy. A government-issued report saved as a scanned image PDF, say on environmental conditions, may be the most consumable form for the public at large.

But at the same time it provides little underlying data for an environmental scientist to draw alternative conclusions from. It lacks precision. A table of worldwide temperature measurements would be of little value to the public at large because only environmental scientists understand the climate models with which conclusions can be reached, but high precision is what matters to those environmental scientists who want to analyze it.

The principle of promoting analysis and reuse of open government data is a primary concern when considering data quality. Large volumes of data are useless if they cannot be analyzed with automated, computerized processes. Therefore when using terms such as accuracy and precision for open government data, they should always be with respect to some automated process to analyze the facts in the data. They do not refer to whether a recording captured the physical details of an event but whether a computer-assisted analysis can determine what happened during the event.

Precision and accuracy are both intertwined with cost. It may be possible to achieve high precision and high accuracy in automated processing of any the data, but only at high cost. When we ask for a database with high precision and high accuracy, we mean at a reasonable cost. When a government agency unnecessarily — or deliberately — increases the cost of attaining high precision or accuracy by delivering data in a less useful format, those who want to use the data may be rightly upset.

When the cost of high precision and accuracy becomes prohibitive, data intended to expand government transparency becomes of limited value. Data quality is the suitability of data for a purpose taking into account the cost of obtaining acceptable levels of precision and accuracy. Figure 1 shows various data formats on axes of accuracy and precision.

Figure 1. This figure shows where different data formats fall on axes of high and low precision and high and low accuracy.

Figure 1. This figure shows where different data formats fall on axes of high and low precision and high and low accuracy.

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book