Sunlight as a Disinfectant

The origin of the phrase

One of the most commonly perceived problems in government is corruption. Although 2009 rankings in the Global Integrity Report put the United States near the top on measures of anti-corruption law, procurement, and the budget process,1 corruption remains one of the most popular problems-to-fix in the open government community here.

Transparency has a long history as a tool for government oversight. Today’s anti-corruption movement focuses around a few sentences by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (1916–1939), who wrote in Other People’s Money shortly before his time on the court:

Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman. And publicity has already played an important part in the struggle against the Money Trust.2

But Brandeis wasn’t talking about government corruption at all. In fact, considering today’s scrutiny of investment banks for their role in Greece’s looming default, curiously high IPO prices of technology companies, and the 2008 world-wide recession, it’s frightening that Brandeis was writing about these sorts of issues 100 years ago. The “Money Trust,” composed of investment bankers like J.P. Morgan, suppressed competition and liberty through the control of credit by being both the bank and the investor.

Brandeis criticized the investment bankers for making a profit by shifting the risk of investments to others: by hiding the names of the sources of securities and relying on the deposits in their banks for their own company’s investments. The investment bankers at the time used their deposits to invest in and obtain majority shareholder control over corporations, creating what Brandeis called interlocking directorates. By having majority control over the rail road, telegraph, and other corporations that were also their banking clients, the barons controlled who could invest in what. “Can full competition exist among anthracite coal railroads when the Morgan associates are potent in all of them?” Brandeis wrote. The way Brandeis explained it, it was as if the investment bankers had created their own small nation of corporations and took a tax (commission) each time money exchanged hands between any of the corporations under their control. The root of the problem, according to Brandeis, was a pervasiveness of conflicts of interest throughout large financial transactions.

The future Supreme Court Justice called on the Money Trust to be broken through legislation, addressing the problem from two directions. On the one hand, Brandeis proposed an out-right ban on interlocking control: “The nexus between all the large potentially competing corporations must be severed, if the Money Trust is to be broken.” But the other part of his proposal was to require greater dissemination of information regarding the risks of securities and the motives of investment bankers. In his famous line about sunlight, Brandeis was just warming up for the pages that followed on which he printed the details of suspect transactions and his proposal to require additional information to be printed in prospectuses. “[T]he disclosure must be real . . . To be effective, knowledge of the facts must be actually brought home to the investor, and this can best be done by requiring the facts to be stated in good, large type.”3

Brandeis’ writing was a part of a movement to change financial services regulations. Shortly after his book was published the Clayton Antitrust Act and Federal Reserve Act were passed in response to the centralization of financial power in just a few banks, and the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act prevented investment banks from taking deposits (though this was later undone by the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act in 1999, which some believe was a direct precursor to the 2008 crash).

The parallels between Brandeis’ world in 1914 and the world today are striking. Just replace “investor” with “voter” and “corporation” with “elected official.” Conflicts of interest in government are pervasive. Transparency helps the public make better decisions, and although Brandeis did not mention it, transparency can also be a disincentive for bad behavior that has not yet occurred. Although in Paradoxes I argue that these aren’t necessary consequences of transparency, they are often true and underlie many successful government transparency projects.

Sunlight Foundation’s transparency applications and related work

Brandeis’ quote is the origin of the name of the Sunlight Foundation. As Brandeis spoke of the conflicts of interest in the Money Trust, the Sunlight Foundation draws attention to the conflicts of interest in government. For instance, using their InfluenceExplorer.com project, which draws on data collected by the Center for Responsive Politics, Sunlight Foundation reported in June 2011 that Rep. John Mica and Rep. Bill Shuster, who proposed a bill privatizing Amtrak, had conflicts of interest stemming from campaign contributions. “Four of [Shuster’s] top five top contributors have ties to the railroad industry and could benefit if Amtrak’s assets are privatized,” they wrote. Contributions from railroad industry-associated individuals beat out most other industries in contributions to Mica.4 Brandeis would be turning in his grave.

Sunlight was primarily a grant-making institution at first. But a small project that began in 2006 changed that. That year was a mid-term election year in which a series of scandals involving Republican congressman threw the majority to the Democrats. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who on election night became the presumptive next Speaker of the House, announced that the next two years would be “the most honest, most open, and most ethical Congress in history.”5 It was in this climate of cleaning house and standing up to corruption that a small community project turned into substantive, long-term policy work.

John Wonderlich, then a telemarketing manager in Pittsburgh, posted a note on DailyKos (a left-leaning blog) recruiting help for a citizen journalism project. The goal of this project, the Congressional Committees Project, was to assign one person, a regular citizen, to each committee and subcommittee in Congress. That person would follow the committee closely and report back what the committee was doing to the group in a non-partisan way. The project was all set to begin, just waiting for Congress to come back from winter recess, when the “new media”6 staffer for Pelosi contacted Wonderlich and asked to have the group collect some feedback about how Congress could be more transparent in the coming years by making better use of technology. The request from Pelosi’s office ended the committees project as the telemarketer from Pittsburgh shifted his attention to leading what became the Open House Project, a formal response to Pelosi’s request.

The Open House Project, sponsored by the Sunlight Foundation, issued a report on May 8, 2007 at a press conference held in the basement of the U.S. Capitol building and in front of C-SPAN cameras. After many months of deliberation among a wide group of open government advocates, Wonderlich, Miller, myself, and several others presented the report recommending technology-related improvements to congressional transparency in the areas of legislative data, committee transparency, preservation of information, relaxing antiquated franking restrictions that kept congressmen off of social networks, ensuring the Congressional Record reflected accurate information, access to the press galleries, improving disclosure reporting, access to Congressional video, coordinating web standards, and sharing with the public the reports of Congress’s research arm, the Congressional Research Service.

One of the project’s first successes was how its recommendations on franking, written by David All and Paul Blumenthal, influenced the outcome of the 2008 House and Senate rules changes that allowed Members to connect with their constituents through social media7. It is hard to remember it now, but for many years Congress’s internal rules actually forbade Members of Congress from participating in social networks like Facebook, stifling new ways Members of Congress and their constituents could stay in touch. And it wasn’t even clear to transparency advocates that they even should, since participation in one network might constitute an endorsement of a particular business. Endorsements then and now are rightly forbidden by congressional rules. But times quickly changed, congressional rules changed, and as it turned out, social media in government became much more of a public relations tool rather than a way to have a genuine dialog with the public.

Most of the remaining recommendations sadly still remain on the movement’s wish list, but the project was crucially important because it became a cornerstone of the policy work of the Sunlight Foundation. Wonderlich is now Sunlight’s policy director and is a registered lobbyist.

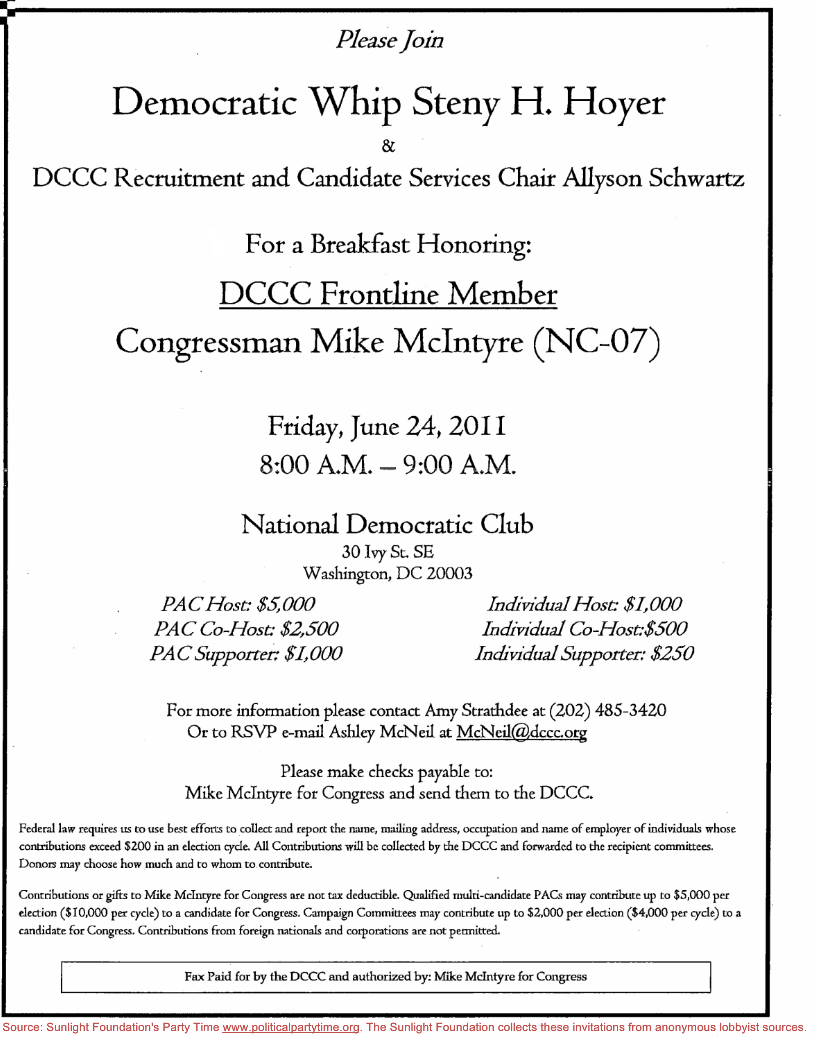

Sunlight’s Party Time website (politicalpartytime.org) documents the “political partying circuit”: the continuous stream of fund-raising events taking place in D.C. restaurants and clubs. Party Time does a remarkable job of showing the public conflicts of interest, the gross amount of time lawmakers spend raising money, and the way money yields access. The website does that by showing scans of event invitations, like the one shown in Figure 1. In this invitation to an event for Rep. Mike McIntyre, an individual who wishes to attend must contribute at least $250 to his campaign, and a Political Action Committee who wishes to have someone attend must contribute at least $1,000. For those who contribute more, special honors are given such as being a party “host,” which might translate into a few minutes with McIntyre or Rep. Steny Hoyer, the Democratic whip who the invitation boasts will be in attendance.

Did McIntyre even need any of that money? McIntyre seemed to have enough to get himself elected since he gave $206,889 or 16% of his 2009-2010 war chest to the national and local Democratic Party organizations, which used the money to help other Democrats get elected.8 It wasn’t enough to get him a committee chair position, however. See Corruption. (I don’t mean to single out this particular event. It is nothing unusual.)

Figure 1. Sunlight Foundation’s Party Time (politicalpartytime.org) project documents the fund-raising events that pervade the lives of Members of Congress.

Figure 1. Sunlight Foundation’s Party Time (politicalpartytime.org) project documents the fund-raising events that pervade the lives of Members of Congress.

Launched in July 2008, Party Time began collecting fundraiser invitations from anonymous sources, scanning and entering them into a database, and making them publicly searchable and viewable. The site includes an API and a bulk data download revealing over 12,000 invitations in the database at the time of writing.

Since invitations typically have different honorary levels of “sponsorship” and different minimum amounts for individuals and Political Action Committees, all with different terminology, it is difficult to reliably summarize the contribution amounts for particular levels. But for a first approximation using the site’s bulk data download, the average minimum donation required of an individual attendee came out to about $700, and $1,375 for PACs. Those levels have remained relatively stable since 2006. This is one way to quantify the price of access to our elected officials, though it’s very rough. For comparison, the current legal maximum contribution an individual may give to a candidate in an election is $2,500, and PACs may give $5,000.

Party Time’s FAQ concisely explains its purpose as something of a mix of civic educator and oversight tool:

By shining sunlight on these parties, the Sunlight Foundation hopes to provide another way for citizens to see how policy is influenced by insiders . . . There’s nothing wrong, or demeaning or sleazy about [lobbying]. However, we do believe that to make informed decisions, citizens need access to full and rapid disclosure of how lobbyists ply their trade [and] Seeing who is trying to influence their representatives, and how, provides valuable information.9

Much in the same way that professional journalism embodies a we-report-you-decide ethos, compared to advocacy journalism, Sunlight Foundation applications often focus on just-the-facts without making a case that the facts support any particular position.

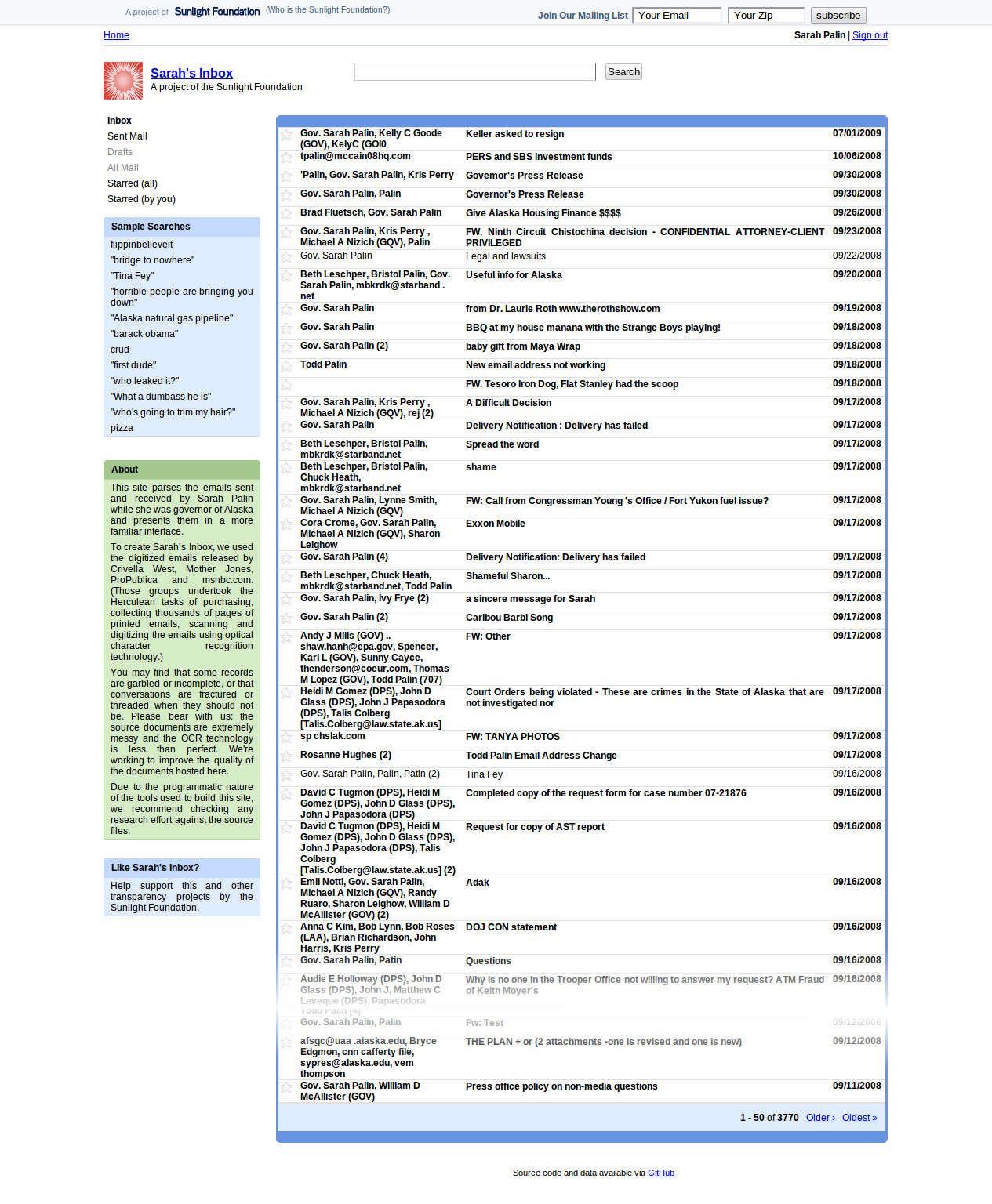

Elena’s Inbox (elenasinbox.com, created in 2010) and more recently Sarah’s Inbox (sarahsinbox.com, created in 2011, shown in Figure 2) put archived public emails of public figures into a searchable Gmail-lookalike interface. The former posted the emails of Supreme Court Justice nominee Elena Kagan from her time a decade earlier as White House counsel in the Clinton administration. The latter posted the emails of Sarah Palin from her time as Alaska governor. When Sarah’s Inbox was created, Palin was a possible Republican presidential nominee, and she had been a vice presidential candidate several years earlier, making her emails of interest to the public. Palin’s emails were released in 24,000 printed pages by the state of Alaska in June 2011 in response to a 2008 request from Mother Jones. Although the emails were initially requested in the investigation of ethics complaints against Palin aides, and hoped to be relevant for the 2008 elections, their value in 2011 was as vague as Palin herself had been about whether she would be running for president.10 The email dump didn’t reveal any new scandals, but it did provide useful insight into Alaskan politics, as in this exchange between Palin and her chief of staff about Alaska’s congressman:

From: Michael A Nizich Subject: Don Young Date: Sep 16, 2008

Congressman Don Young would like to have a word with you sometime today if possible. His office has called and would like for you to call when your schedule permits.

From: Gov. Sarah Palin Subject: Re: Don Young Date: Sep 16, 2008

Pls find out what it’s about. I don’t want to get chewed out by him yet again, I’m not up for that.11

Figure 2. Sunlight Foundation’s Sarah’s Inbox (sarahsinbox.com) is a Gmail-like interface to the data dump of emails acquired by Mother Jones and scanned by a collaboration of institutions.

Figure 2. Sunlight Foundation’s Sarah’s Inbox (sarahsinbox.com) is a Gmail-like interface to the data dump of emails acquired by Mother Jones and scanned by a collaboration of institutions.

The emails in the release were, like this one, mostly about scheduling. But what is interesting about these projects is the innovative approach to government transparency that is one part data and one part design, or user experience. The email data dumps (or, more precisely, paper dumps) posed a needle-in-a-haystack problem for investigative journalists. It was apt then for a user interface to the data to pay homage to Google, the king of search, by cloning its Gmail interface. But the design choice was more than homage. The application of a familiar paradigm, that of reading your email, made the scale of the data that much more manageable.12

The projects are also examples of the dirty work of transforming unstructured stacks of paper into a clean database. In a blog post entitled “How Not to Release Data,” Sunlight’s labs director Tom Lee explained how each step of the White House’s release process for Kagan’s emails caused problems with the data, making it considerably less useful for transparency: printing the emails on paper, scanning the printouts with OCR (optical character recognition) to recover the text, and then encoding the scans in PDF format. Handing over the original digital files would have allowed Lee to build a more accurate tool in less time. But as Lee has since noted13 there were reasonable reasons for why the White House went through so much trouble, namely their statutory requirement to redact certain information. It’s not that redaction couldn’t be done digitally, but in fact there just aren’t good tools to do it. There are often unexpected reasons, usually legal reasons, that explain odd government behavior when it comes to transparency.

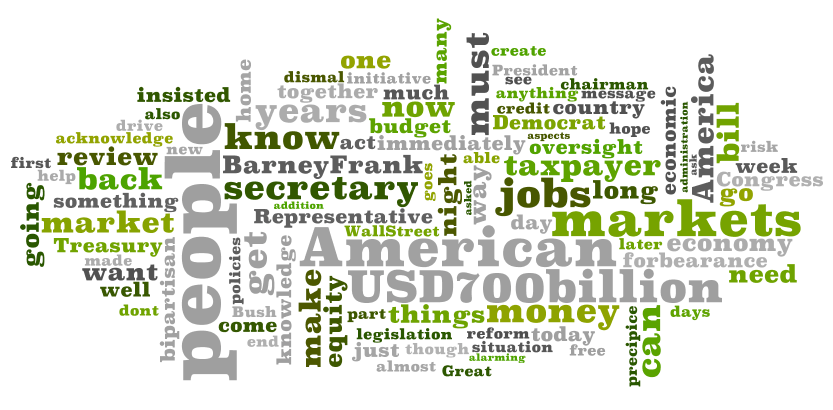

In a 2008 Sunlight Foundation project called CapitolWords.org the text of speeches on the House and Senate floors were turned into word clouds (Figure 3 top). A word cloud is a visualization of the frequency of key terms in text through variation in the size, color, and position of the terms in the image. The largest, brightest, and typically most centrally positioned words are the most frequently occurring in the text, the other words shown smaller, dimmer, and more peripheral. The middle image in Figure 3 is based on Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s remarks on the expensive economic bail-out plan in 2008. The image was created in 2008 by C. J. Olesh and Jeremy P. Bushnell using text transcribed by The New York Times and Wordle, a tool where you can paste in text and it creates a word cloud.14

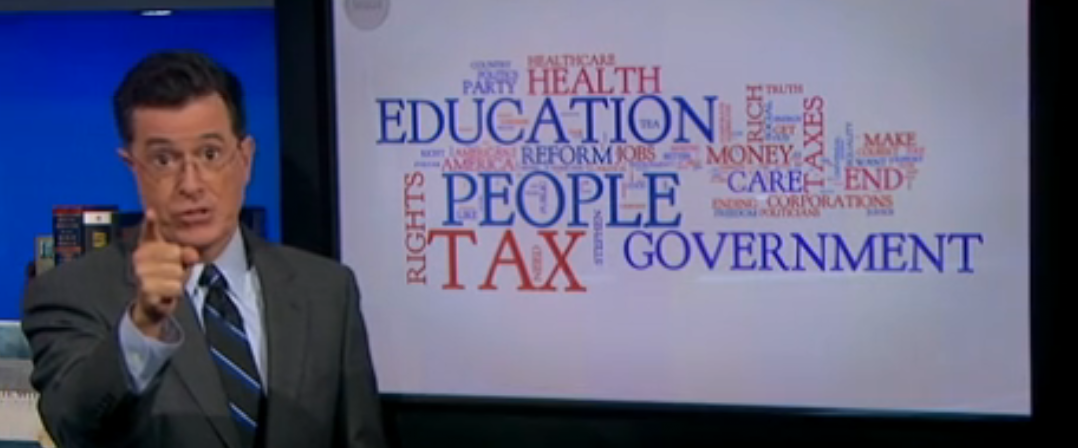

Figure 3. Top: CapitolWords.org in 2008 (this screenshot from infosthetics.com). Middle: Word cloud by C. J. Olesh and Jeremy P. Bushnell of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s remarks on the economic bail-out plan, drawn with Wordle.com by Jonathan Feinberg. Bottom: What contributors to the Colbert Super PAC think the PAC should stand for, with words weighted by the amount contributed to the PAC. (The Colbert Report, Aug. 16, 2011.)

Figure 3. Top: CapitolWords.org in 2008 (this screenshot from infosthetics.com). Middle: Word cloud by C. J. Olesh and Jeremy P. Bushnell of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s remarks on the economic bail-out plan, drawn with Wordle.com by Jonathan Feinberg. Bottom: What contributors to the Colbert Super PAC think the PAC should stand for, with words weighted by the amount contributed to the PAC. (The Colbert Report, Aug. 16, 2011.)

Word clouds are both computation and art. Olesh and Bushnell’s cloud rotates some words vertically, making it more visually interesting, thereby increasing its effectiveness as a visualization. The cloud is drawn in shades of green which is thematically appropriate to the topic of the speech (money), and intensity, size, position, and orientation relate the prominence of the words in the text. Whereas Wordle lays the words out compactly, the 2008 CapitolWords spreads the words out diffusely, with the most prominent words focused in the center. Mixing form and function the cloud included a bar graph and word counts, which is helpful when trying to precisely describe what the word cloud is showing.

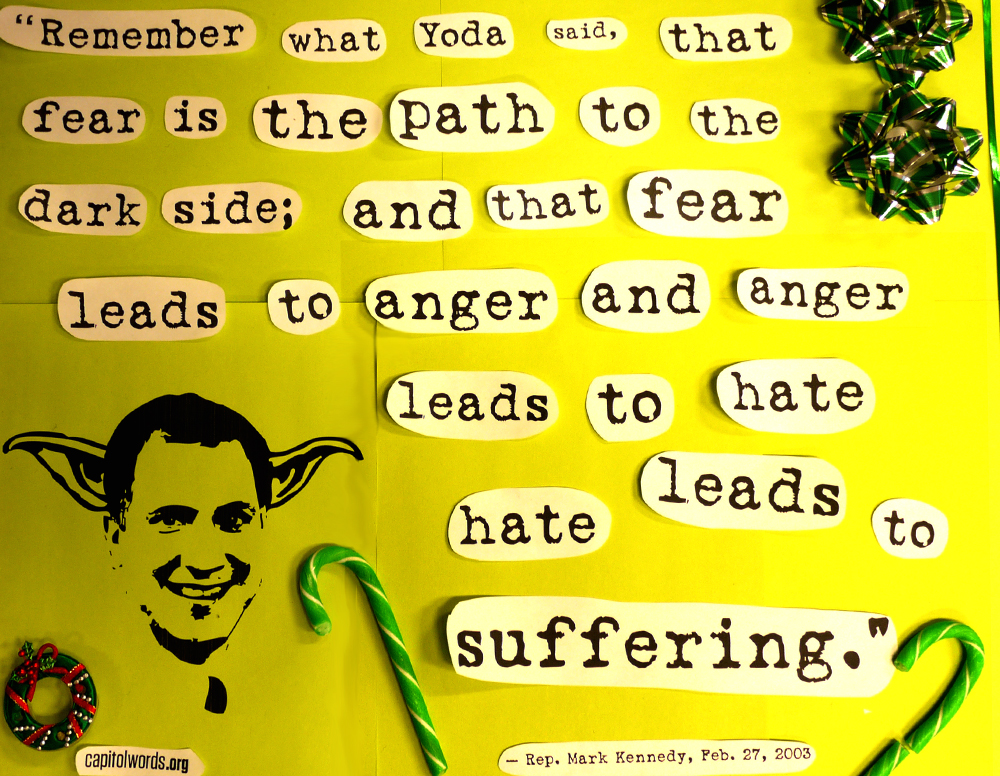

The re-launched CapitolWords.org in December 2011 took congressional floor speeches to a new artistic level, making them into illustrated holiday cards (Figure 4). Of course no longer a word cloud, the holiday cards mash up what was learned from the word cloud data analysis with a fantastical illustration technique to make a novel and extremely compelling visualization of what Congress is talking about.

Figure 4. Sunlight Foundation’s 2011 Capitol Greetings project (capitolwords.org/holidays) turned excerpts from speeches on the floor of Congress into holiday greeting cards. This card illustrates Rep. Mark Kennedy’s re-telling of Star Wars in a speech date Feb. 27, 2003. Clicking the card on Sunlight’s website even plays the audio from the speech.

Figure 4. Sunlight Foundation’s 2011 Capitol Greetings project (capitolwords.org/holidays) turned excerpts from speeches on the floor of Congress into holiday greeting cards. This card illustrates Rep. Mark Kennedy’s re-telling of Star Wars in a speech date Feb. 27, 2003. Clicking the card on Sunlight’s website even plays the audio from the speech.

There are a number of methods for generating a word cloud. Jonathan Feinberg, the author of Wordle.com, explained his algorithm on Stack Overflow:

Count the words, throw away boring words, and sort by the count, descending. Keep the top N words for some N. Assign each word a font size proportional to its count. … Each word ‘wants’ to be somewhere, such as ‘at some random x position in the vertical center’’.

In decreasing order of frequency, do this for each word: place the word where it wants to be, while it intersects any of the previously placed words move it one step along an ever-increasing spiral. That’s it. The hard part is in doing the intersection-testing efficiently…15

I include Feinberg’s explanation here because it is interesting how turning art into a repeatable procedure is one of the tools in a data hacker’s tool belt. Rarely is art repeatable — the CapitolWords holiday cards are each the work of an artist, for instance — but when it works it gives the rest of us non-artists a tool we did not have before. (Some other methods of constructing word clouds, with source code, are linked from the StackOverflow page linked in footnote just above.)

The details of how to construct the word cloud affect its meaning. In a word cloud depicted in the August 16, 2011 episode of The Colbert Report, the words indicated what contributors to the Colbert Super PAC thought the PAC should advocate. Colbert presented two word clouds, one where words were sized according to the number of times they were suggested and the one shown in Figure 3 (bottom) where words were sized according to the dollar amount contributed to the PAC by the individuals suggesting each word. Colbert’s two clouds showed markedly different ideas, namely the difference between what people want and what people are willing and able to pay for. Even when much of the artistic process is made repeatable, the data hacker must wear several hats to make the right choices for how to best represent the information locked away in the data.

Professional journalism versus advocacy journalism

Not all of Sunlight Foundation’s work is policy-agnostic, but most of the organization’s advocacy can be found in their reporting, lobbying, and community organizing arms rather than in their development shop called Sunlight Labs. Inside the Labs, projects such as ClearSpending (a data quality analysis of information on usaspending.gov), the Open States Project (a national database of pending state legislation), and Better Draw a District (which draws attention to gerrymandering; the name is a play on The Colbert Report’s “Better Know a District” series) are all, at least on the surface, transparency for transparency’s sake. Although each of these projects relates directly to important questions of government process and the ability of citizens and oversight bodies to identify conflicts of interest, the projects neither indict Members of Congress, lobbyists, or contractors on any particular wrong-doing nor advocate particular policy changes. Instead, the applications are often the infrastructure needed for researching and reporting on particular cases, used both by the media at large and by Sunlight’s own reporting and policy staff, who do call out individuals on particular cases of conflicts of interest (as I noted above) and do advocate for policy changes (such as greater funding for government operations that enable transparency and enhanced financial disclosures).

The work of Sunlight Labs is a lot like the work of professional journalism, as I began to say above. The professional journalist works in the public interest to uncover facts, present all sides, and above all else remain free of any bias. But the Labs has an edge over traditional journalists. The Labs’ projects are exclusively open source, and where possible they also promote open data. In the terms of reporting, that means that others can vet all of their sources and step through all of their reasoning. Open source and open data projects are inspectable, even reproducible. A journalist rarely makes available all of their sources, sometimes with good reason, but mostly because they have no place within their medium to practically do so. An article also excludes the journalists intermediate thinking and work — what information did the journalist find but choose to put aside? Open source applications like Sarah’s Inbox suffer none of these problems. Software can neither have a bias, although its creators certainly can, but the source code itself serves as a full disclosure of how any bias affected the code, since the code is there to be seen.

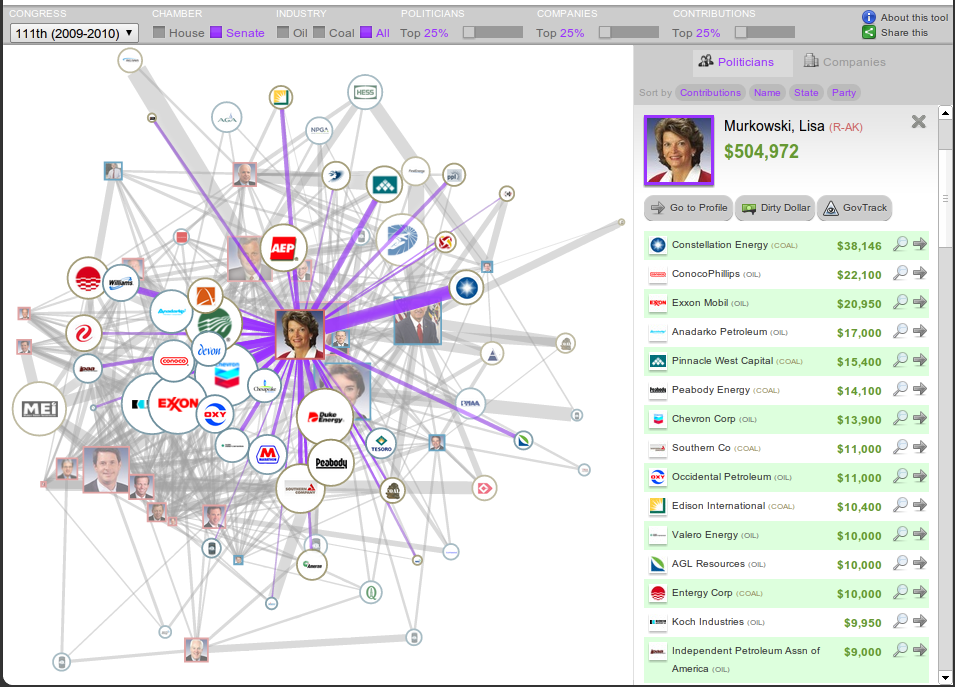

Professional journalism is not the only form of journalism. Advocacy journalism has fallen out of favor, probably because it has been confused with propaganda, but it still exists and remains an important part of government oversight. Dirty Energy Money (dirtyenergymoney.com) is one example of advocacy journalism based on government transparency. If successful lobbying is about who you know, then an analysis of the networks of relationships among government actors is an important tool for finding conflicts of interest. Dirty Energy Money, developed by Greg Michalec and Skye Bender-deMoll for Oil Change International, shows the relationships between coal and oil energy companies and Members of Congress through campaign contributions from employees of those companies to congressional campaigns (see Figure 5). The network visualization permits the user to relatively easily explore relationships, moving from contributor to senator and then to other contributors. In this project, unlike some others, indictment is clear. According to Oil Change International, energy companies are “pumping their dirty money into politics.” Dirty Energy Money’s position on their issue does not make their visualization any less informative than if it had been created by someone else.

Figure 5. Dirty Energy Money from Oil Change International shows the relationships between coal and oil energy companies and Members of Congress through campaign contributions from employees of those companies to congressional campaigns. http://dirtyenergymoney.com/view.php

Figure 5. Dirty Energy Money from Oil Change International shows the relationships between coal and oil energy companies and Members of Congress through campaign contributions from employees of those companies to congressional campaigns. http://dirtyenergymoney.com/view.php

-

Louis D. Brandeis, 1914, Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It. Frederick A. Stokes Company: New York. Originally published in Harper’s Weekly. Page 92. Also http://www.law.louisville.edu/library/collections/brandeis/node/196. ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2011/06/30/railroads-heavily-invested-in-privatizing-amtrak/ ↩

-

A “new media” communications staffer was the person responsible for maintaining their boss’s presence in online communications systems such as social networks. ↩

-

http://www.theopenhouseproject.com/2008/10/03/franking-reform-a-happy-ending/ ↩

-

http://www.opensecrets.org/politicians/expend.php?cycle=2010&cid=N00002356&type=I ↩

-

http://motherjones.com/politics/2011/06/sarah-palin-email-saga ↩

-

The idea for a Gmail interface was suggested by Bob Brigham, who was unaffiliated with Sunlight, but credit goes to Sunlight Foundation’s Tom Lee for a sleek implementation. http://sunlightlabs.com/blog/2010/elenas-inbox/ ↩

-

at his panel in South by Southwest 2012 ↩

-

http://politicaltagclouds.wordpress.com/2008/09/26/sarah-palin-at-the-republican-national-convention-september-3-2008/ ↩

-

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/342687/algorithm-to-implement-a-word-cloud-like-wordle ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book