Why I Built GovTrack.us

Motivation

I’ve never particularly liked politics. It’s all the antagonism that really gets to me, and the way political parties try to advance their position for the next election at the expense of good public policy. I do like civics, legal theory, and the process of governance, which is how I ended up in a class my freshman year at Princeton in 2001 called “The Speech is a Machine.” “Parts of the law that never clashed before now contradict each other,” read the syllabus.1 Software code is speech in the sense that it is expressive, giving it potential protections under the First Amendment. Code can be elegant and creative, both in the problem it solves and in the way it solves it. And software is a machine because software does something, bringing it under the regulations covering trade, patents, and actions. The class was about this conflict.

The class was timely. It was the hay-day of music sharing over peer-to-peer networks like Napster. In class I participated in a mock court case that hinged on whether the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) could prevent playing DVDs you’ve just purchased, and out of class I was writing articles for the school newspaper on how the class’s professor Andrew Appel and his colleague Ed Felten were being threatened by the music recording industry over publishing their research on digital watermarks (a technology in development at the time to thwart unauthorized copying of digital files).2 Peer-to-peer file sharing networks began getting shut down several months later by litigation from the recording industry — the recording industry thought the software crossed over the speech-machine divide. In response, students on college campuses began building their own small sharing networks with surprisingly advanced infrastructure (such as scanning publicly shared folders). And then the first lawsuits against college students came for running sharing networks. One suit was against a Princeton sophomore in 2003.3 It felt harsh, and personal, and it motivated many of us there at the time to consider how our technology expertise could be used in the public sphere.

The class was the first time that I saw that lawmaking was a dynamic process with interests competing for the best policy for themselves. In the case of the DMCA, the major record labels and other corporate holders of valuable copyrights showed up to the policy-making game and got what they wanted: stronger copyright laws. It seemed to me that in the case of the DMCA, Members of Congress had either failed to understand the DMCA or simply caved to the business interests that lobbied for protection for their antiquated industry. But why didn’t the American public hold Congress accountable for a patently wrong law? From class I was familiar with the website THOMAS.gov, the legislative resource created by Congress in 1995 after the Contract with America. THOMAS was a comprehensive public record, but the details made it daunting to navigate for anyone but legislative professionals. (THOMAS.gov was replaced in 2014 with Congress.gov.)

Looking back, I can think of three other services that I knew of that inspired me to dig into government’s Big Data. First was the Center for Responsive Politics’s campaign finance website OpenSecrets.org, which I learned of from working on the student newspaper. Second, in the late 1990s I had subscribed to email updates for the votes of my Members of Congress through a free service of America Online and Capitol Advantage (now a part of CQ Roll Call). So I knew that there were other useful ways besides THOMAS to present the truly vast amount of information processed by Congress and to help the public track the bills that interested them. I thought of both OpenSecrets and the votes service as a part of the old Web 1.0, though.

The third service inspired me in a different way. It was an open source project out of MIT’s Media Lab named Government Information Awareness. The project aimed to track the potential conflicts of interest of Members of Congress, and it was at the same time also a parody of an ominous-sounding government program, Total Information Awareness, which would mine large databases of information about the public for terror threats.4 The question in my mind, as in the minds of the MIT developers, was with better tools could the public hold Congress accountable?

At the same time I felt insulted by the government. The Library of Congress, which ran THOMAS, obviously had a database of all of the public information that went into powering THOMAS. But the Library did not make the database, in raw form, available to the public to innovate with. The difference is like being given refrigerator poetry magnets that have been glued into a pre-written sonnet. You can appreciate the sonnet, sure, but the glue has limited the obvious potential that comes from being able to rearrange the pieces and discover new meaning. Data is the same way. THOMAS (the sonnet) was a vital resource for the American public during its 20-years in service, but there is potential locked away when the information behind THOMAS (the poetry pieces) cannot be re-purposed or transformed into other applications. The limited functionality on THOMAS frustrated me5, and by withholding their legislative database from the public, Congress and the Library of Congress seemed to be saying they should be the sole source of information on what Congress was doing. That’s not only unfortunate, it is un-American.

Getting the data

I first asked the Library of Congress to share its data in 2001. They respectfully declined. In 2009 an Act of Congress — or a small part of an act that I worked on with Rep. Mike Honda’s office6 — encouraged the Library to move forward with sharing their database. Rep. Bill Foster introduced a bill just on this point in 2010, but the bill was not voted on. The House Republican leadership in 2011 promised to make available the House Clerk’s legislative database, and some progress on that has been made with the launch of docs.house.gov in January 2012. But it’s now 13 years since I first inquired about it and the core data still remains locked away. The hold-up has been that the Library’s law division does not see publishing data as a part of its mandate authorized by Congress, and getting both the House and the Senate to agree on updating the Library’s mandate is slow going.

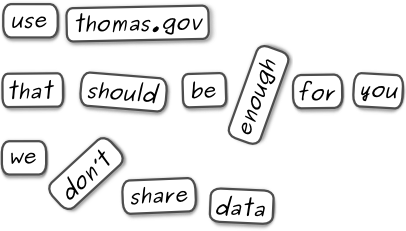

Figure 1. Data is like refrigerator poetry. This is how the Library of Congress responds — well, if they spoke in haiku — when you ask them if you can repurpose their underlying legislative data.

Figure 1. Data is like refrigerator poetry. This is how the Library of Congress responds — well, if they spoke in haiku — when you ask them if you can repurpose their underlying legislative data.

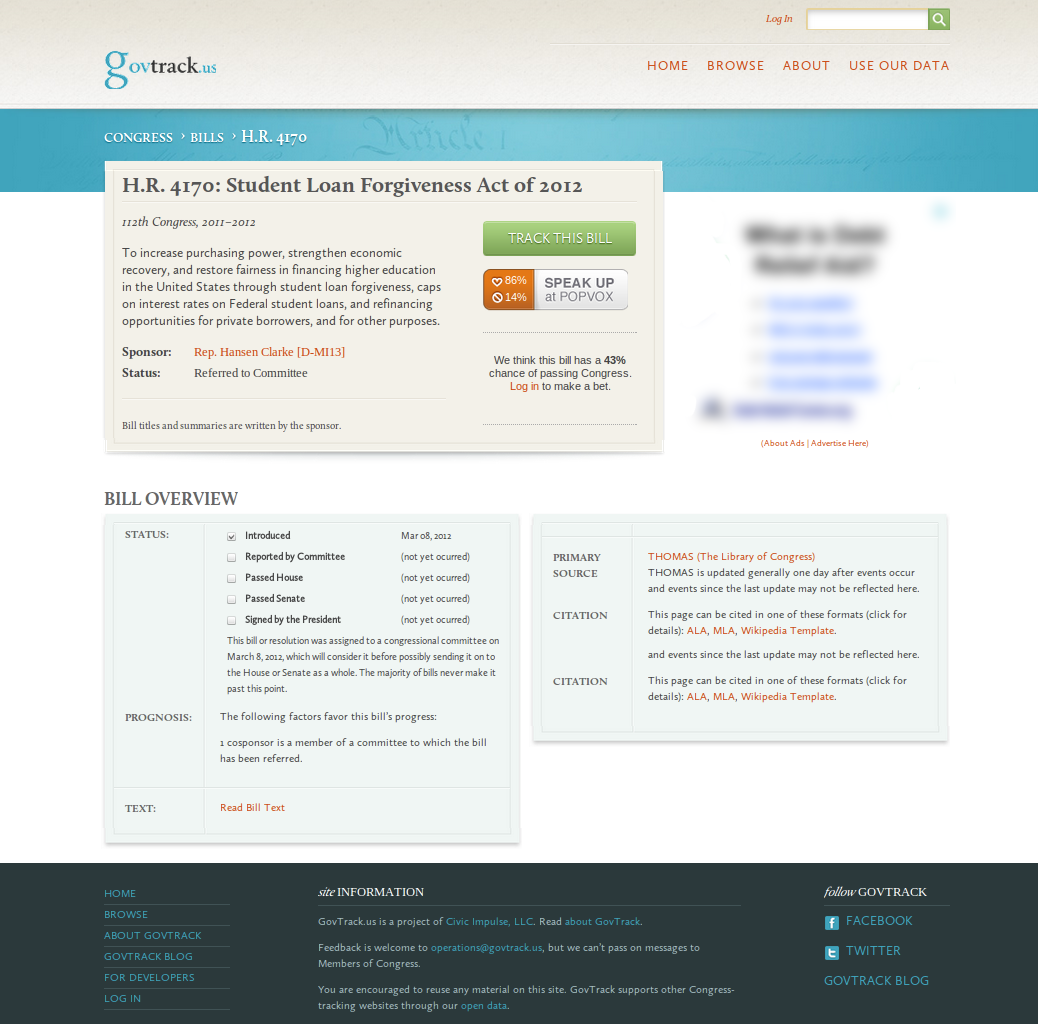

It was several years later in 2004 that I finally finished and launched GovTrack.us, a website that tracks the activities of the U.S. Congress (Figure 2). It was one of the first websites world-wide to offer comprehensive parliamentary tracking for free and with the intention to be used by everyday citizens. Most of the information on the site can be found elsewhere, but in so many different places and in formats that they are hardly useful to the American public. For instance, voting records are found for the House of Representatives on the House’s website and for the Senate on the Senate’s website. The status of legislation is listed on Congress.gov (then THOMAS), but schedules of hearings to discuss the legislation are scattered around several dozen Congressional committee websites (though this is now being improved on docs.house.gov). With many small programs GovTrack “screen-scrapes” all of these websites, normalizes the information, and creates a large database of Congressional information.

So GovTrack runs itself. These screen-scrapers periodically go out to the government websites, including THOMAS, to fetch the information they have on Congress. It scans for new bill status, votes, and other information in a completely automated way. Screen scraping is programmatically loading up web pages, looking at their HTML source, and extracting information using simple pattern matching. It’s not interesting programming work, and screen scrapers are easily confused because of the multitude of ways in which unstructured information can be displayed. For instance, several years after finishing the bill status screen scraper I learned — because my scraper was crashing — that a bill might not have a sponsor (which has been the case with debt-limit-raising bills because no one wants to take responsibility for it). I hadn’t anticipated these cases, and unanticipated cases cause problems, sometimes leading to incorrect information being shown on the site.

(Today the screen scrapers are maintained in an open source community-run project called The United States Project at theunitedstates.io and on github, created in 2012. Eric Mill, then a developer for the Sunlight Foundation, and Derek Willis, a reporter for The New York Times, have been incredible partners in centralizing all of our legislative data gathering code.)

Contextualizing Congress

The legislative database is the first part of GovTrack. With the data assembled, i.e. the refrigerator poetry pieces unglued, I was able to create what you see when you visit GovTrack.us: the status of legislation, RSS feeds for the activities of Congress, interactive maps of Congressional districts, voting records, biographical information about Members of Congress, and change-tracking for the text of bills.

Figure 2. www.GovTrack.us, a project I began working on in 2001 and launched in 2004. Here it is in early 2012. The advertisement has been blurred.

Figure 2. www.GovTrack.us, a project I began working on in 2001 and launched in 2004. Here it is in early 2012. The advertisement has been blurred.

Being able to read the bill that Congress is about to pass is a little like the experience of being in the capital for the first time and seeing the Declaration of Independence under glass at the National Archives. Our nation isn’t abstract. There it is on my screen right there. Or, there it is in my inbox. GovTrack is able to offer a unique view into Congress, giving the public a deeper understanding of how our government works and getting citizens more engaged. So I like to think that when a bill number — like H.R. 3200 — is said on the air of a late night TV show, such as The Daily Show (Figure 3) or Late Night with Jimmy Fallon7, that I might have contributed to the greater public consciousness of the legislative process.

Figure 3. John Oliver parodies Schoolhouse Rock’s “I’m Just a Bill” in a commentary on the implementation of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform bill (The Daily Show, Jul 28, 2011).

Figure 3. John Oliver parodies Schoolhouse Rock’s “I’m Just a Bill” in a commentary on the implementation of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform bill (The Daily Show, Jul 28, 2011).

Re-assembling a complete database of legislation in Congress creates new possibilities. Novel statistics about the performance of Members of Congress become computable once the data is available to run the number crunching.

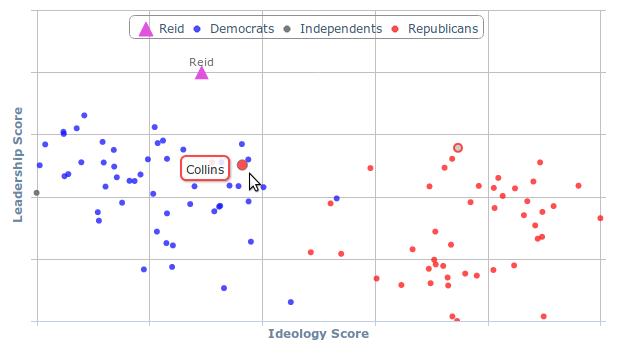

For instance, GovTrack computes leadership and ideology scores for Members of Congress based on their patterns of sponsorship of bills — shown in Figure 4. Charts like these help visitors to put the information they see in context. In GovTrack’s leadership-ideology charts, leadership is shown on the vertical axis (higher means more a leader) and ideology (liberal vs. conservative) is shown on the horizontal axis. In the figure, Sen. Harry Reid, the senate majority leader, is marked with a triangle. If you did not know he is the majority leader, his position at the top of the chart would give you an idea. The figure also highlights Sen. Susan Collins. Well known as a moderate Republican, Collins’s ideology score reflects just how moderate she is. She is more liberal than some Democrats.

Figure 4. GovTrack computes leadership and ideology scores for Members of Congress based on their patterns of sponsorship of bills.

Figure 4. GovTrack computes leadership and ideology scores for Members of Congress based on their patterns of sponsorship of bills.

The statistical analysis doesn’t look at the content of bills or the party affiliation or anything else about the Members of Congress it is analyzing, but it is able to infer underlying behavioral patterns some of which correspond to real-world concepts like left-right ideology. To compute the ideology scores, I form a matrix with columns representing the senators and rows also representing the senators. Then I put a 1 in each cell where the senator for the column cosponsored any bill by the senator for the row, and I put zeros everywhere else. Then I use a statistics package to perform a principle components analysis on the matrix, in this case a singular value decomposition, and what comes back happens to be ideology scores.8

The leadership scores are based on Google’s PageRank algorithm. Google’s algorithm for ranking pages is widely known: the more links you get the higher ranked your page, but links you get from highly ranked pages are even better. In Congress we can look at the network of who is cosponsoring whose bills similarly. When a representative cosponsors a bill, it is a vote of confidence not only for that bill but also a vote of confidence or loyalty for the bill’s sponsor. If we imagine Members of Congress each as a “web page” and each time a Member cosponsors another Member’s bill it is a link from one “web page” to that of the other, then the PageRank algorithm is going to reveal the ranking of the implicit loyalties directly from the public, official behavior of the Members of Congress. And it does.9

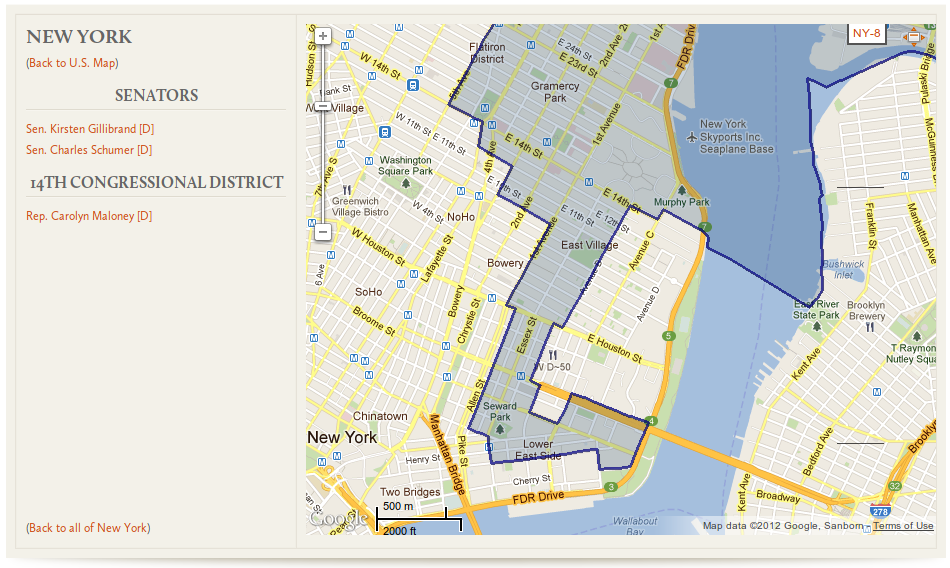

Statistics are one way to give context. Another is to use personal geography. By overlaying Census geographical data with Google Maps, GovTrack made it possible to reliably determine your congressional district by zooming to street level. (This wasn’t possible in 2004!) That is crucial if you live near a district boundary, which is common in metropolitan areas because those districts are geographically quite small. Address databases only have about a 95% accuracy, but maps are almost always right. See Figure 5.

Figure 5. GovTrack combines GIS data from the Census with Google Maps to create zoomable congressional district maps.

Figure 5. GovTrack combines GIS data from the Census with Google Maps to create zoomable congressional district maps.

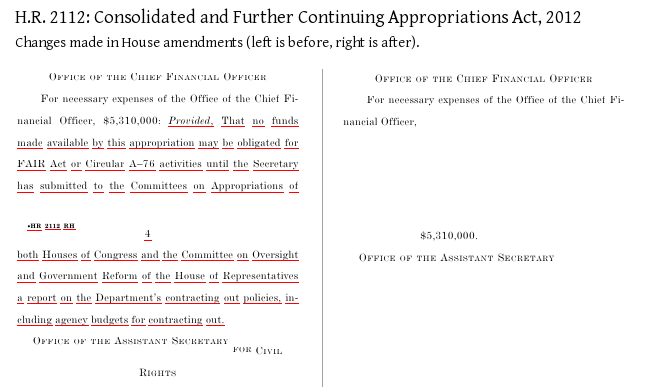

Another form of context is to show changes over time. The deletion of eight lines from a House appropriations bill is highlighted with automatic red-lining using a tool for bill text comparison that I developed while starting POPVOX — see Figure 6.

Figure 6. GovTrack and POPVOX.com show changes to bill text made during the committee and amendment processes. Here the deletion of eight lines in a House appropriations bill is highlighted, based on the bill text comparison algorithm I developed for POPVOX. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr2112/text

Figure 6. GovTrack and POPVOX.com show changes to bill text made during the committee and amendment processes. Here the deletion of eight lines in a House appropriations bill is highlighted, based on the bill text comparison algorithm I developed for POPVOX. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr2112/text

Sharing data

In 2012, GovTrack.us was used by more than 5 million individuals. But it reaches even more citizens than that if you count visitors to websites and mobile apps built by others on top of GovTrack’s legislative database. When I opened up the source data that powers GovTrack, a collection of mostly XML files, others started to see the potential for building other tools that shed light on government processes in new ways. The three biggest reusers of the data have been OpenCongress.org (originally created by the Participatory Politics Foundation (PPF) but now run by the Sunlight Foundation), MAPLight.org, which puts a new spin on the connections between money and politics (see Corruption for more thoughts on MAPLight), and the mobile apps and APIs created by the Sunlight Foundation. Another interesting use of GovTrack’s data was IBM ManyBills, which was a visualization tool named after their ManyEyes project but for congressional legislation. Many dozens of websites and mobile apps have popped up relying on GovTrack data all trying to give the public a new way to get a grasp of their government — I’m sure there are dozens I’m not even aware of.

Going forward

GovTrack is ad-supported and, lately, self-sustaining. Unlike most projects in this space, GovTrack isn’t non-profit. There’s no tax-exempt organization behind it and I don’t take grants10. My work on GovTrack is accountable to no one but myself and my users, and in some years the ad revenue is even enough to hire part-time help — I have been very lucky.

Now, truth be told, I started working on GovTrack.us in the early 2000’s because I thought the sort of transparency GovTrack would create could empower voters to make better decisions. But more than ten years later, never have I heard of a case of information found on GovTrack — whether it be a voting record or the text of a bill — changing anyone’s mind about who they would vote for in an election. At the time I began building the site I hadn’t yet even voted in an election myself, and it was grossly naive to think that that could have been the case. The reason is simple. At least one person in any election is not the incumbent, and if the challenger did not serve in Congress then GovTrack has nothing to say about whether you should prefer that candidate or not. The incumbent’s legislative record doesn’t actually help much in that decision.

Today I view the goal as something more basic and along the lines of civic education. Through greater understanding, I hope to reduce cynicism and mistrust in the cases where it’s not really called for. Sometimes it’s called for. But not always. For instance, many bill titles end with “and for other purposes.” I have been asked many times how one could support a bill that is so vague that it does not even say what it will do, and are congressmen trying to pull one over on us by granting themselves indefinite authority for “other purposes”? The reality is that it is just a title. The full text of the bill, which everyone can read, always spells out the details and often in the most rigorous lawyer-speak. So I hope to make bill text more accessible. Without this understanding of how Congress works, it is easy to be cynical. But this cynicism does no good.

-

The syllabus is still posted at http://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/spr01/frs136. ↩

-

Amy Harmon. 2003. Suit Settled for Students Downloading Music Online, The New York Times. ↩

-

Michelle Delio. July 4, 2003. Government Prying, the Good Kind. Wired. The MIT project didn’t get off the ground, but some of their work lives on in GovTrack. I bootstrapped my database of Members of Congress from Government Information Awareness’s CSV file, and GovTrack’s numeric IDs for the Members of Congress that were serving in 2003 continue to be the IDs from MIT’s project. ↩

-

Amusingly, GovTrack is now older than THOMAS was when I started building GovTrack. I wonder if users find the limited functionality of GovTrack as frustrating as I felt with THOMAS! ↩

-

a paragraph in the report attached to H.R. 1105, the legislative branch appropriations bill ↩

-

On Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Fallon and The Roots’ Tariq Trotter regularly “Slow Jam the News.” On Sept. 14, 2009, the two jammed about the pending health care reform bill (though they said the bill number incorrectly). In May 2012 episodes of their shows, Fallon and Jay Leno mocked Congress by citing a study by the Sunlight Foundation on the Flesch–Kincaid readability levels of Members of Congress’s floor speeches. ↩

-

Similar analyses have been made by Professor Keith Poole at http://voteview.com/ and Don Smith at http://truthsite.org/political-visualization/us-senators.html, but with different statistical methods. ↩

-

Inspiration for a leadership analysis came from a suggestion from college friend Joseph Barillari. ↩

-

One very small grant from the Sunlight Foundation went to a contributor many years ago to improve the display of bill text. ↩

Open Government Data: The Book

Open Government Data: The Book